Published on 16.12.2024

Nesli Hazal Oktay is a designer-researcher and educator from Istanbul, Turkey; based in Tallinn, Estonia. Since 2019, she has been working at the Design Faculty of the Estonian Academy of Arts. Her research interests include embodied, participatory, and speculative approaches to interaction design, focusing on the phenomenology of intimacy. She has taught various courses and conducted workshops at both undergraduate and graduate levels in Estonia, Latvia, Denmark, and Belgium, focusing on interaction design and speculative design. Currently serving as an Associate Professor of Interaction Design, she is also involved with the Sensorial Design research group at the Estonian Academy of Arts. neslihazal.com

In the constantly evolving landscape of design, understanding the target audience is an essential yet complex step. Traditional tools like mood boards are often used in the early phases to translate design opportunities into visually stimulating collages. Mood boards typically consist of visual collages with stimulating images, colours, material swatches, textures, drawings, and physical objects.1 Building on this method and inspired by the philosophy of phenomenology, I have integrated sensorial mappings into my design courses at both bachelor and master’s levels since 2021. This method invites designers to move beyond purely visual observation and engage deeply with their lived, sensory experiences to build empathy with the target audience in their everyday life settings. By focusing on the rich, embodied interaction between the designer and the environment, sensorial mappings open up new ways of understanding the target audience – through the senses and beyond the surface of observation.

Phenomenology, which focuses on the lived experience, is nicely captured by Maurice Merleau-Ponty's words: ‘The body is the vehicle of being in the world.’2 In this view, our bodies are how we exist in and interact with the world. We sense, engage with, and ultimately make meaning of the material world through our physical experiences. When designers enter the environments of their target audience, their observations are shaped by the interconnectedness of lived bodies and the material world. However, over the years, I’ve noticed that design students often associate observation with sight. Yet, human experience is embodied and extends far beyond what can be seen. It is not always processed cognitively or emotionally but is felt through the sensing, moving body. Therefore, I propose sensorial mapping as a method where the human body is understood as a sensory being, moving beyond the classic five senses.3 In phenomenology, this is known as the lived body, the medium through which we experience and make meaning from the world.

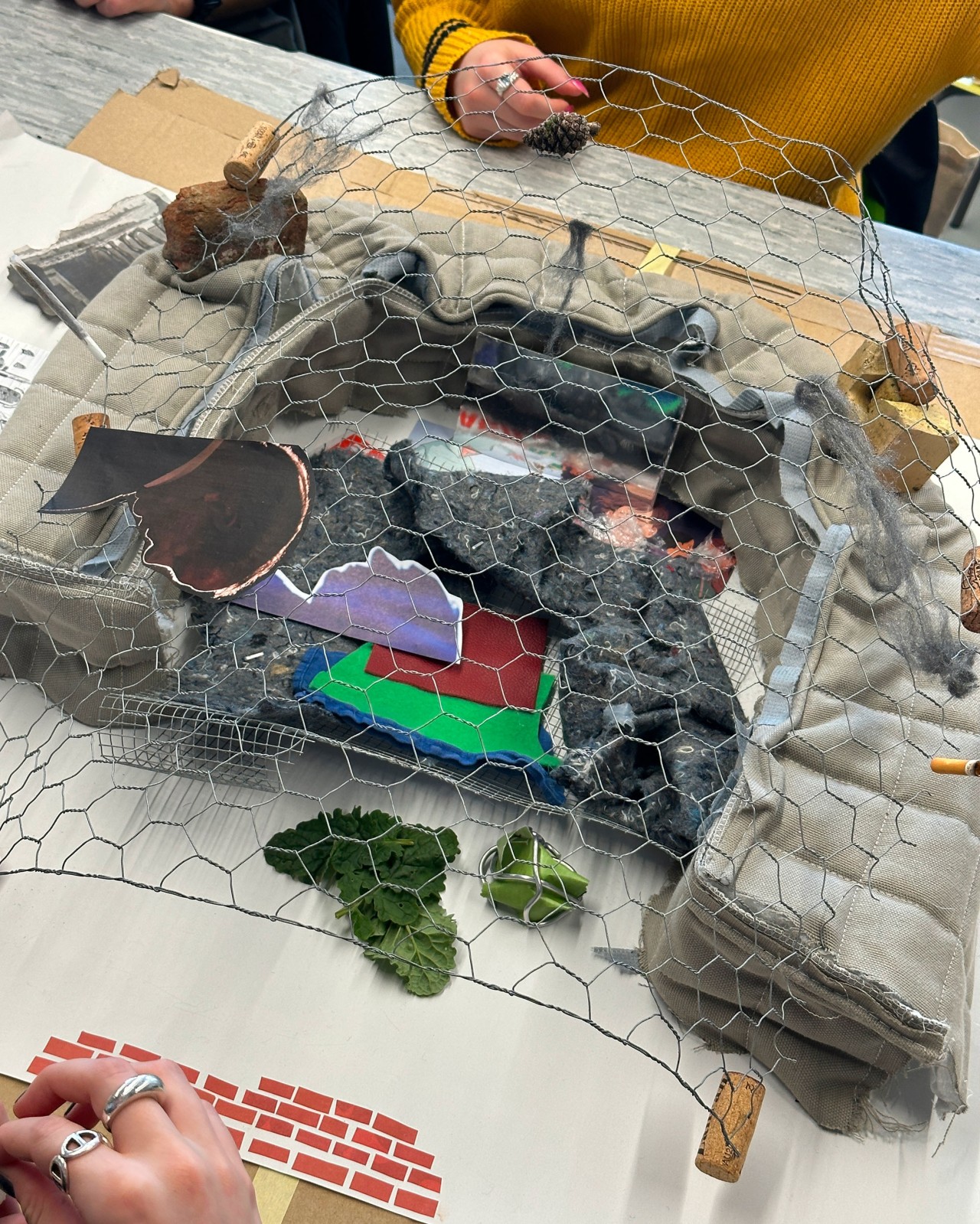

To engage with the method of sensorial mapping, designers work in teams, beginning with individual reflections on the lived, sensory aspects of their observations. These reflections, captured through notes and sketches, are next shared in a team setting. Together, the team then creates a mood board using tangible materials – branches, surplus textiles, or other found objects – to articulate their sensory experiences. This tangibility provides a way to bridge the gap between experiential and linguistic understanding, translating felt experiences into something physically graspable. To describe and illustrate this method, I turn to a recent workshop I led for third-year undergraduate design students in 2023. This two-day workshop was part of a week-long collaborative international course delivered at the Estonian Academy of Arts. The course focused on social design and a sensorial approach in the designing process and the students were from countries such as Belgium, Estonia and Hungary. The course asked how a visit to the participants’ living environment could inform the co-design process of an expressive artefact created between design students and the participants. It began with the workshop I led, including a visit to a centre run by a welfare organisation in Estonia, where children without parental care or those struggling with behavioural or substance abuse issues receive professional assistance. During this visit, students were asked to observe the environment not just with their eyes, but with all their senses. Subsequently, they were asked to translate their observations into a sensorial map. This map was later used as a starting point to brainstorm and ideate on the artefacts to be co-created with the residents of the centre. In the next section, I will use my first-person experience to illustrate the process of sensorial mapping:

I enter the room. Around thirty young designers gaze at me, their eyes filled with curiosity. I begin by introducing them to the human senses, expanding their understanding beyond the traditional five. As I explain that we will visit the centre to uncover co-design opportunities for the residents, I emphasise that the task ahead is not about thinking or feeling in the abstract. It’s about sensing – ‘When experiencing the environment, do not solely observe what’s going on around you, but also turn inwards and ask: What do I sense being here? What does it mean to sense this place?’ Some students look puzzled, so I explain that they may begin by focusing on a few specific senses to warm up. We arrive at the centre. A staff member welcomes us with an overview of the facility and its residents. As we walk through the common area, a child notices us and hurries away, going to a bedroom that, we later learn, reflects the individual style of its resident. Moving on, we enter the music room, its walls covered with egg cartons donated to soundproof the space. Students take notes, and for the first time we move outside to the backyard. The weather is gloomy, yet imagining the yard in full bloom on a summer day brings warmth to our group. As we continue the tour, residents on the second-floor glance at us, we wave at them and they wave back, giggling. There’s a brief moment of connection – lighthearted and warm, in contrast to the heavy atmosphere that comes later. As we conclude the visit, the staff member informs us that one of the residents very recently passed away. The air feels thick with unspoken grief, and silence is evident in the group as we make our way back to our studio. I wonder how the students will capture these nuanced, embodied experiences in their sensorial maps. The next day, it’s time for the group discussion where each team presents their boards. One team shares: ‘After the visit, we began by having an open discussion about our notes and noticed that we all experienced a sense of suffocation. Despite the greenery, there was a plastic kind of freedom. But then, we all saw the smiles of the residents. That’s when we sensed light at the end of the tunnel. It was airy, light, a breath of fresh air.’

Designing is both a structured and creative process, and understanding a target audience is never simple. I offer sensorial mapping as a creative tool for transforming cognitive and emotional insights into tangible, sensory expressions. This approach can help designers immerse themselves in the lives of vulnerable target audiences where taking photos or videos during an observation may not be appropriate or allowed. Therefore, this method relies on the reflection-in-and-on-action4 of the designers supported by the documentation of the experience through note-taking and sketching. I argue that by engaging with and reflecting on their own sensory perceptions, those of their team members, and possibly of their audience, designers can foster a deeper, more empathetic connection, allowing for design processes and outcomes that resonate on multiple levels. In conclusion, sensorial mapping moves beyond visual observation, relies on reflection, and offers a pathway to deepen designers’ connection to both their audience and themselves, as sensory beings intertwined with the world.

References

- Lucero, A. ‘Framing, aligning, paradoxing, abstracting, and directing: How design mood boards work,’ DIS '12: Proceedings of the Designing Interactive Systems Conference (2012), pp. 438–447. <https://doi.org/10.1145/2317956.231802>

- Merleau-Ponty, M. Phenomenology of Perception: An Introduction. (Routledge, 2002).

- Kuusk, K., Oktay, N. H., & Demir, A. D., ‘Sensorial Design: Feel, Move, Interact!,’ Leida 1(1). <https://leida.artun.ee/en/issues/technocriticism/sensorial-design-feel-move-interact>

- Schön, D. A. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. (1992, Routledge). <https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315237473>