Published on 16.12.2024

Lijana Natalevičienė is an art historian and a senior researcher at the Lithuanian Culture Research Institute. Her scholarly interests include modern and contemporary Lithuanian and Western European decorative arts and design, and the relationship between tradition and modernity. Natalevičienė has also studied the social history of fine crafts in Lithuania and has published several monographs on Lithuanian textile artists.

Lithuanian ethnic design has been an under-examined field for a long time, despite the fact that it occupied an important place in the cultural life of the state in the 20th century. Due to the complex geopolitical circumstances that Lithuania experienced in the 20th century – two world wars and almost 50 years of Soviet occupation – folk art, and decorative objects created on the basis of it, were a source of national feeling that mobilised citizens and fostered national identity. It is not difficult to understand why this happened. The question arises about the state ideology’s relationship with ethnic culture: When is it a tool to mobilise and represent society, and when does it become a tool for manipulation that serves the system?

The aim of the article is to try to identify the reasons for the vitality of ethnic traditions and their functional roles in the life of the state. The role of ethnic design under the conditions of different political systems will be examined by following the case of the ethnic design company Marginiai (Patterned fabrics). The choice of Marginiai was determined by the popularity of similar companies around the world. Such enterprises operated in other Soviet republics (Māksla in Latvia, Ars in Estonia). After the WWII, they were also typical of the socialist bloc, where artistic life was centralised and controlled by the state; there were about 150 similar artistic enterprises in the USSR.1

The company Marginiai and the factory Dailė, which operated during the Soviet period and was established on the basis of Marginiai during the first Soviet occupation, is the same company that adapted to the needs of different political systems. It is also interesting that this company did not cease operations during the Second World War in German-occupied Lithuania. All these facts and the financial success of the company under different political systems, raises the question of the role of ethnic design in politics, and the ability of traditional crafts to serve the ideology of both national and occupation regimes.

After regaining its independence in 1918, Lithuania sought to become a modern state with its own distinct cultural identity. Modernism meant progress and a desire to join the Western European community, while the search for national distinctiveness reminded the country of its history and mobilised its citizens for the work of building a modern state. The development of ethnographic handicrafts was encouraged by the nationalist party (Tautininkai) that came to power in 1926 and was the most influential political force in Lithuania during the interwar period. People were encouraged to wear national costumes, decorate their houses with the handicrafts of rural artisans, and wood carvers who made statuettes of Christian saints, were prompted to also create works of secular content. Lithuanians gladly identified with the traditional village, which, due to expanding urbanisation and land reform that started in 1919, was actually becoming more modern. Since traditional crafts were disappearing in the village, cultural policymakers decided to organise the production of ethnographic handicrafts and souvenirs for local and foreign markets.

To this end, the Marginiai cooperative was founded in 1930 to support folk art and home industry. It organised the mass production of ethnic decorative objects (referred to as ‘home industry’). The company’s statutes emphasised the continuation of traditions and economic benefits for thousands of rural craftsmen, and the opportunity for Lithuania to “enter the global market and benefit greatly from it.”2 Such objects were distinguished from authentic folk art by the commercial and serial nature of their production. They served as souvenirs and represented the country in the international arena. Periodicals established the southern regions of Germany, which exported ethnographic handicrafts to America and Great Britain, as examples to be followed.

The Marginiai cooperative was by nature close to early modernist alliances that sought to bring art and mass production closer together. For example, we can find some similarities in the aims of William Morris. However, unlike its counterparts in Europe before WWI, Marginiai came about at the initiative of a state institution (the Chamber of Agriculture) rather than individuals. The rising trend of nationalism and interest in anthropology and ethnology in Europe during the interwar period created favourable conditions for Lithuania’s appearances abroad, presenting it as a country with deep roots in rural culture. A new historical stage emerged related to the national manifestations of the state, which had recently restored its independence, and an institutional initiative determined the greater role of state ideology in shaping the national style of the company’s products as well as its commitment to representing Lithuania in international exhibitions.

The production of small series of wood carvings, textiles and ceramics had to remain below average market prices (“as they are in the market of small towns”) and educate the public in a national spirit. The company planned to bring together folk artists from all regions of Lithuania, support and instruct manufacturers and look for a market for their products within the country and abroad. The company’s plans included the establishment of courses on crafts, publishing activities, and providing craftsmen with tools and raw materials. The first Marginiai store in Kaunas set up according to a design by Vsevolodas Dobužinskis quickly became the hot spot, attracting tourists and individual passersby.

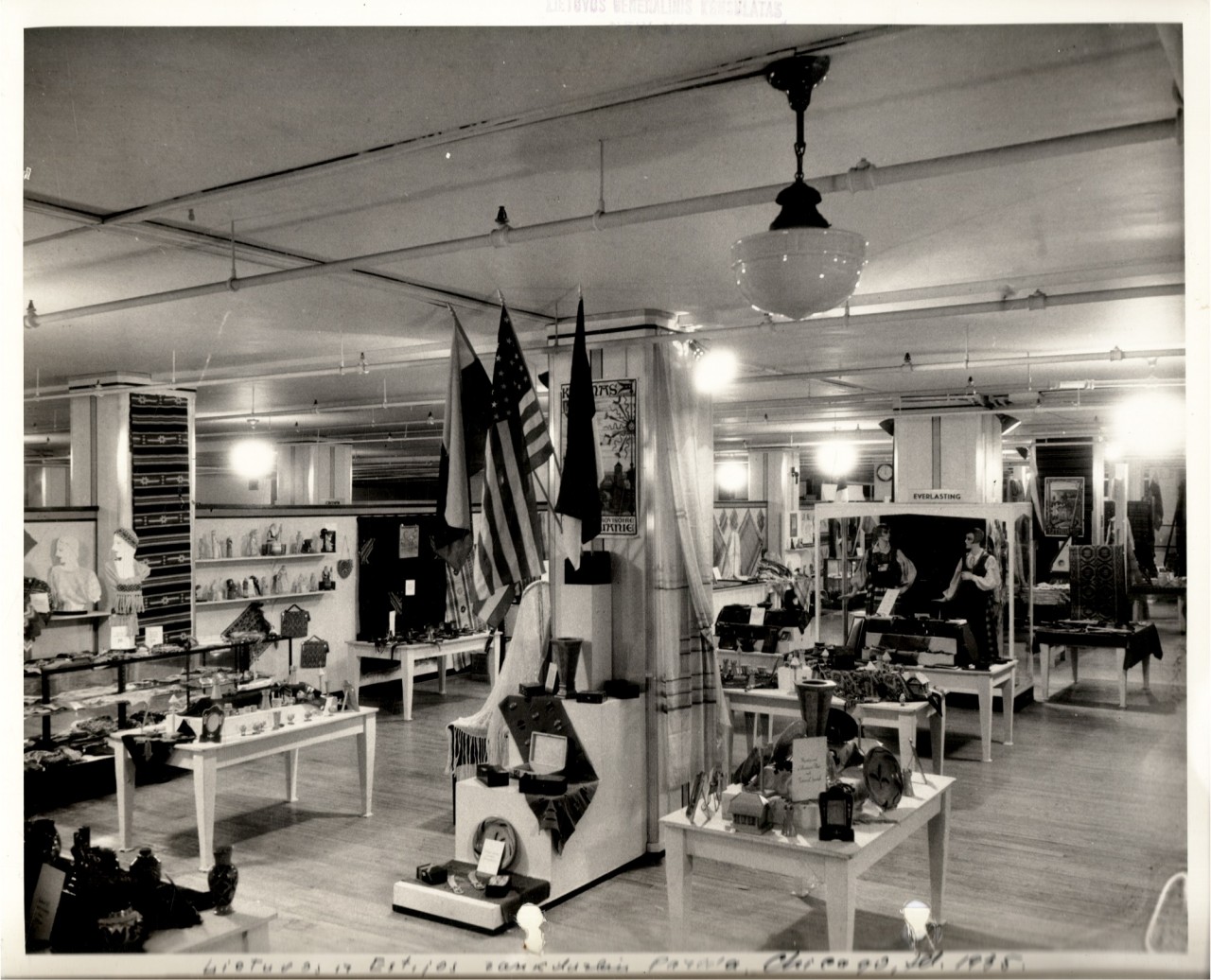

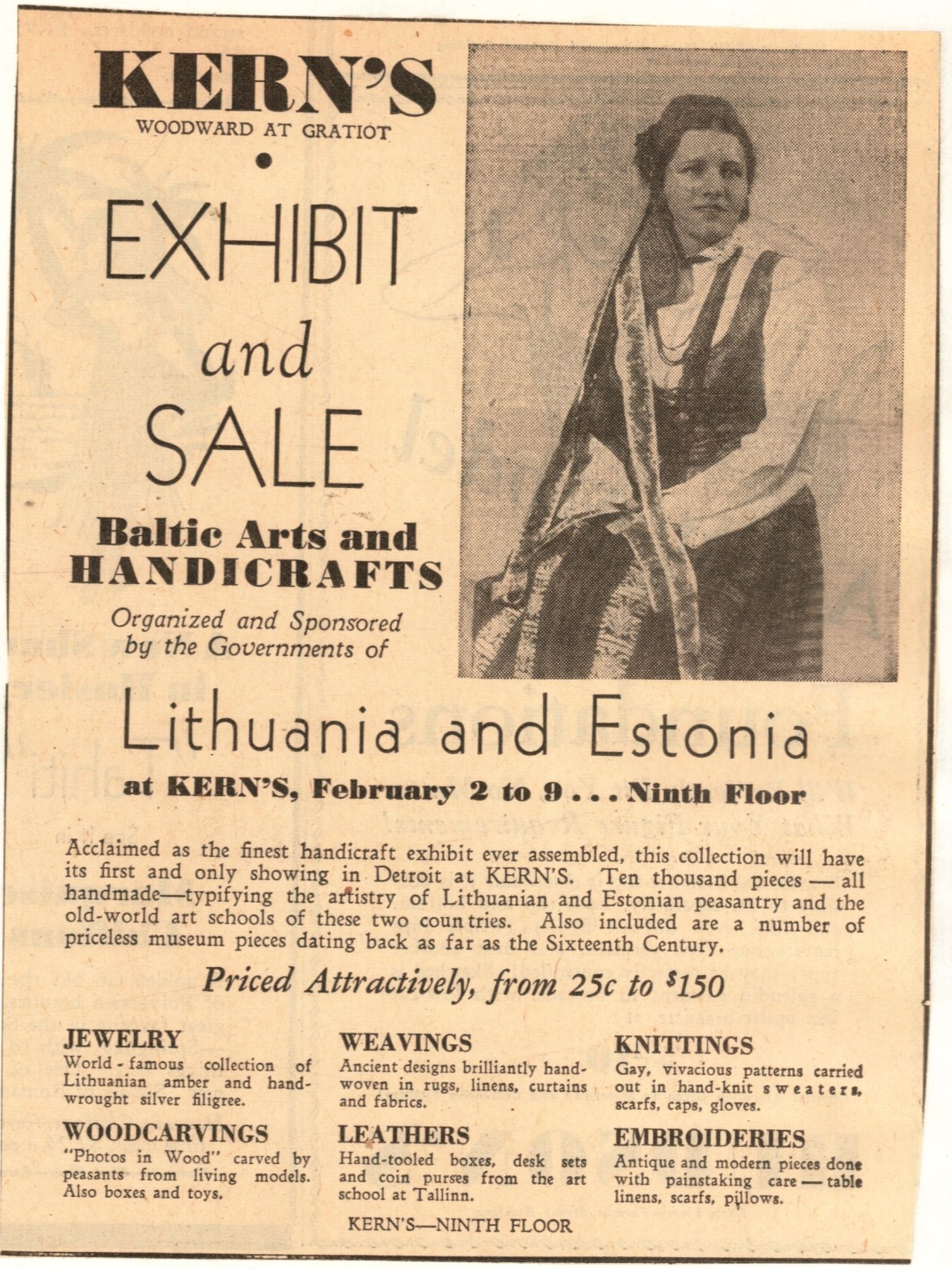

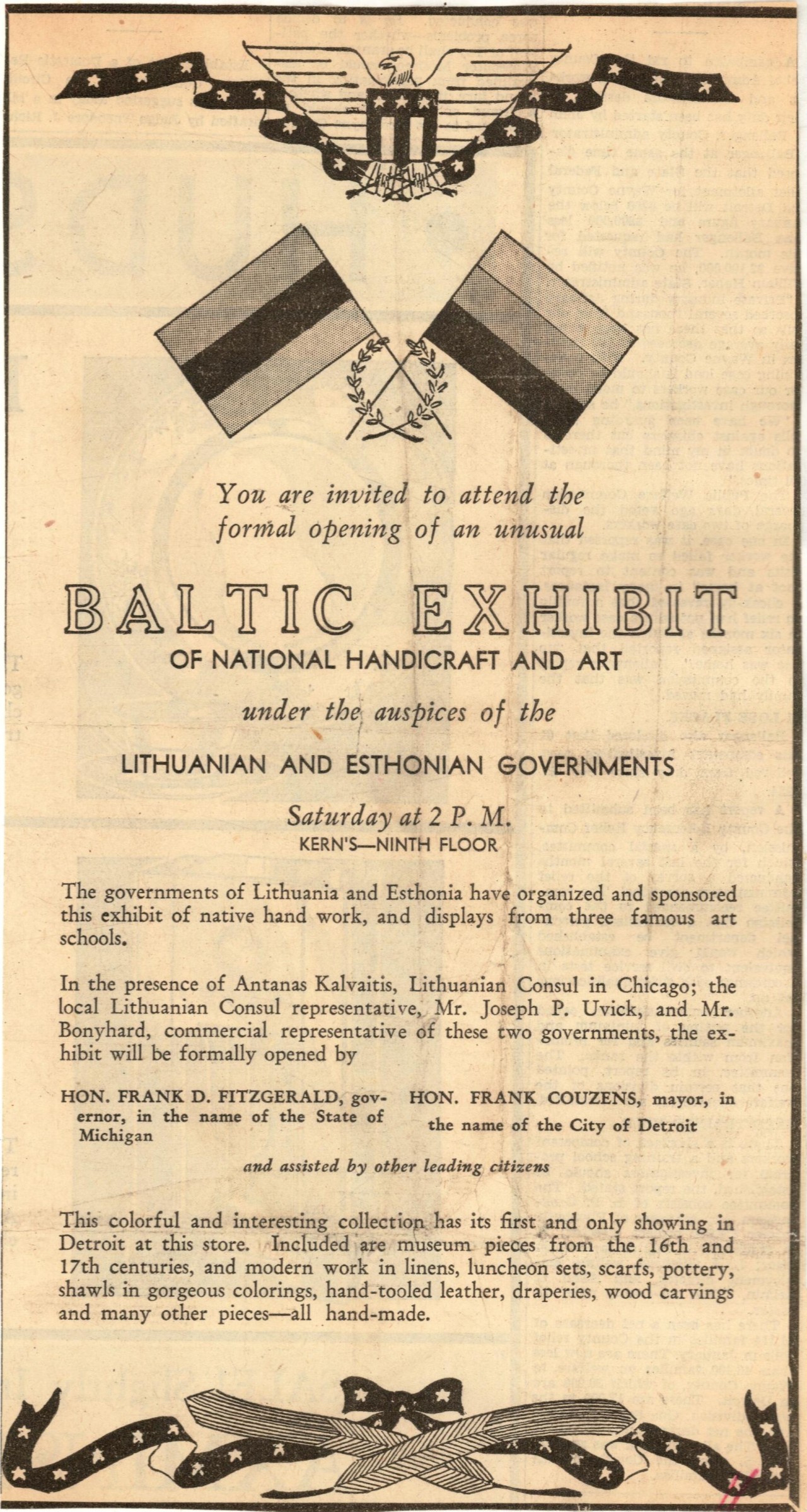

The companyʼs managers started looking for foreign outlets to sell their products. In 1934–1935, the US shopping centres (in New York, Philadelphia, Chicago and elsewhere) featured exhibitions of traditional crafts by Lithuanian and Estonian craftsmen. They were driven by representational and commercial motives. The main supplier of exhibits for these displays was the Marginiai company. Lithuanian and Estonian products were in such high demand that during one week their exhibition in Chicago was visited by 45 thousand people, who bought items worth $500 on the first day. Encouraged by this success, the store’s management decided to establish a permanent department of Lithuanian merchandise by building a Lithuanian cottage.3

In preparation for the 1937 International Exposition of Art and Technology in Modern Life in Paris, the organisers decided to emphasise the country’s ethnographic identity, believing that this exoticism unseen in the West would interest the exhibition’s visitors. Marginiai items were awarded two gold and one bronze medal in different categories. However, the representatives of the younger generation, including Lithuanians in the USA, questioned the validity of such an idea. The hall’s equipment and exhibits emphasised the image of an agrarian state, which was becoming more modern but also nurtured its ethnic heritage. Perhaps for the first time, tensions arose in the public space between the presentation of ethnic identity and the assertion of Lithuanian modernity.

But the situation repeated itself. In 1938, the products of the Marginiai company headed the list of the first International Crafts Exhibition that took place in Berlin from May 28 to July 10 and was organised by the German Labour Front together with the International World Crafts Organisation. Lithuanians refused to participate in the section Industry: The Assistant to the Craftsman and thus Lithuania was one of the few countries that did not display its industrially produced exhibits. The exhibition welcomed what Lithuanians were proud of – traditional costumes, handmade patterned fabrics, wood carvings, amber, and ceramics. In the hall of honour, where, according to the rules of the exhibition, each country was to show its most valuable crafts, Anastazija Tamošaitienė, the instructor of handicrafts, dressed in a national costume, sat at a loom and demonstrated how Lithuanian women weave. In the 1939 World’s Fair “World of Tomorrow” in New York, only Lithuania from the three Baltic countries presented itself. The decision to participate was motivated not only by a desire to represent the Lithuanian people but also because the US had a large expat community.4 The exhibition preparation committee in Lithuania granted Marginiai a 10 thousand Litas interest-free loan for the production of exhibits.5 In addition, the company provided large quantities of fabrics for national costumes to American Lithuanian amateur craftsmen, who participated in the Lithuanian Day of the New York exhibition (according to the terms of the exhibition, each participating country organised its own national day).

The goal of the Marginiai company to bring together folk craftsmen, to promote the spread of a new quality of handicraft in Lithuania and to act as a mediator between manufacturer and buyer was achieved. In 1940, the company’s turnover amounted to 400 thousand Litas.6 A special fund was created to support rural producers. Although the company’s contribution to the local economy was not very significant, it gained a solid position in the country’s culture and satisfied the local need for folk-craft products.

The review showed that both national and occupation authorities viewed fine arts and especially ethnic design as an important means of propaganda that should serve the ideology of the state and international representation. Ethnic design works present the old traditions of an independent state and are therefore important to the citizens themselves as they allow them to identify emotionally with their state. As a result, such products will be popular with the general public at all times. This becomes even more significant in the context of political defence because of the responsibility to pass on national traditions to the younger generation.

References

- Rasa Dargužaitė, Meno pramonė: „Dailės“ kombinatų veikla [Art Industry: Activities of the Dailė Manufactories], (Meno rinkos agentūra, 2020).

- Liaudies menui ir namų pramonei remti bendrovės „Marginiai“ įstatai [Statutes of the Marginiai company to support folk art and home industry], Kaunas, 1930, p. 3.

- Didelis lietuvių estų parodos pasisekimas Čikagoje [The great success of the Lithuanian-Estonian exhibition in Chicago], Naujoji romuva, 1935, Nr. 8, p. 195.

- Lietuva New Yorke [Lithuania in New York], Vairas, 1939, Nr. 3, p. 60.

- Protocol of the meeting of the Organizing Committee for the Lithuanian branch at the New York World’s Fair No. 2, 7 March 1938, Department of Rare Prints of the Vrublevski Library of the Lithuanian Academy of Sciences, f. 245–24, l. 22.

- Lietuvių enciklopedija [Lithuanian Encyclopedia], t. 17, Boston, p. 453.