Published on 16.12.2024

Linda-Maria Varris is a designer and design researcher. In her work, she combines social equality and feminism with contemporary design practices, while being particularly interested in the hidden narratives within design. Linda-Maria Varris has a bachelor’s degree in Industrial and Digital Product Design from the Estonian Academy of Arts, and she has also supplemented her studies at the Berlin University of the Arts. In 2022, Varris’ urinary catheter fastening device (in collaboration with Henry Markus Gregory and Liisa Lepik) won the Grand Prix at the Estonian Design Awards, as well as the Bruno Product Design Award. She currently works as a lecturer in design methods at the Estonian Academy of Arts Department of Product Design.

When talking about tampons and menstrual pads, an image of a carefree and cheerful girl dressed in white skipping through a meadow in bloom might come to mind. Consequently, in store the hand also reaches first for the packaging imitating nature, decorated with green fields and daisies. Menstruation is the body’s natural process, yet these packages often end up in the darkest corners of the shopping cart, and at the checkout they somehow tend to get tucked away under other products. Most women are probably familiar with this taboo, but can we also grasp the broader impact of this stigma on the history, nature, and availability of menstrual products?

According to Aristotle, the universe, and therefore also human existence, is divided into two opposing halves, defined by ten contradictory pairs.1 He similarly distinguishes between the sexes, attributing the so-called darker half, characterised by the body or material to the female, while seeing the male, guided by reason, as the enlightener and creator.2 As the female is positioned on the darker side, so is her body and everything that relates to it. This way of thinking persisted for the next millennia until the mid-19th century, when the women’s movement began to quietly raise its head, gradually breaking down outdated stigmas and perceptions to this day. One of them being the menstrual taboo.

In 1993, Judith Butler criticised in her book Bodies That Matter the modern perception of seeing the body as an object, emphasising that the social ideal or norm attributed to it is almost impossible to achieve. Such ideals have been established by groups in positions of power to help define what is ‘progressive’ and ‘viable’ in society.3 Although Butler uses this theory to make observations on the performativity of gender, it also provides a good framework for analysing menstruation and the stigma associated with it. The menstrual taboo is also a social construction, as it has been perceived as something deviant in society, along with the menstruating body which has been regarded as an abnormal object rather than a human characteristic. Consequently, at least once a month, women are deprived of the image of a normal body – a social illusion.

Over the centuries, menstruation has been seen as something impure and shameful; for example, it has been called a ‘curse’ and there have been claims that menstrual blood is poisonous. To prove the latter, up until the 1930s, scientists still tried to find evidence that menstruating women excrete a toxic substance called menotoxin.4 In addition, women in the luteal5 and menstrual phases have been seen as unstable, sometimes even ill and infectious. For example, in almost all major religions, apart from Western Christianity and Sikhism, the ‘impure’ menstruating women have not been allowed in temples, nor are they authorised to touch sacred objects.6 No wonder then that women feel almost compelled to conceal their periods.

ASK FOR THEM BY NAME – THE JOURNEY OF MENSTRUAL PRODUCTS TO MASS MARKET CONSUMER GOODS

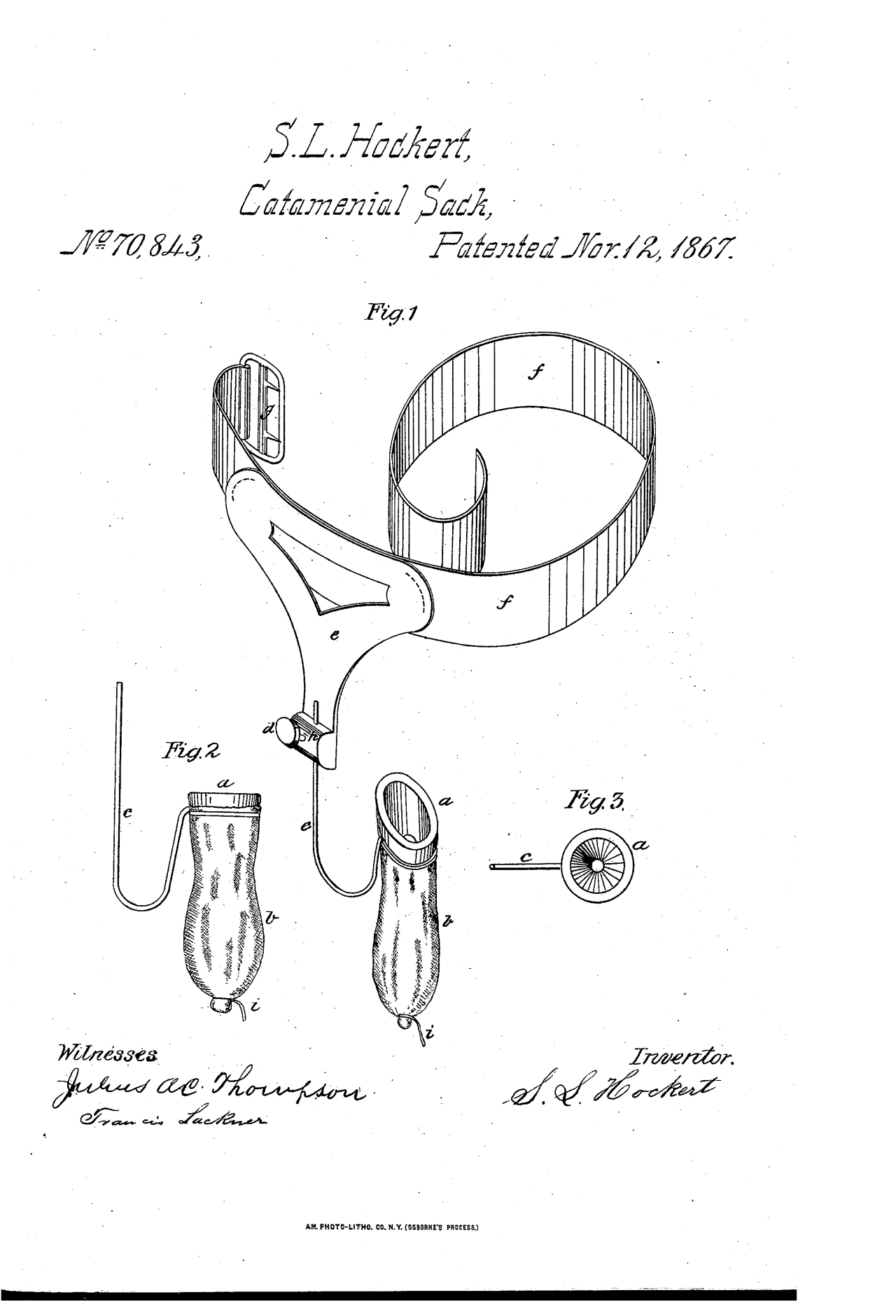

In 1867, S. L. Hockert patented one of the first mass-produced menstrual products. It was the Catamenial Sack7 – a strong rubber container reminiscent of a deflated balloon for collecting blood, held in place by a belt attached to the woman’s body.8 Though at first glance, the visuals of the product resemble medieval torture instruments rather than the foremother of the menstrual cup, the invention still has a symbolic significance. First, Hockert attributed a completely new function to menstrual products – while previous homemade solutions focused on absorbing menstrual blood externally, his product collected the blood internally. And second, it is known to be the first reusable menstrual product that is also easy to clean and store.

The mid-19th century brought new public discussions on the subject of women’s rights, which in turn prompted people to see the potential of menstrual products as mass-marketed consumer goods. This meant that by the end of the century, about a dozen products for this purpose had been patented, including Hockert’s Catamenial Sack. Although the fashion of the era was influenced by simplicity and convenience, which was also what the patented menstrual products aimed for, these goods were largely doomed because of the puritanical attitude towards sexuality (including reproductive health) that dominated at the time. For example, Hockert’s version of the menstrual cup was considered inappropriate to use at the time, as it required women to touch their private parts.

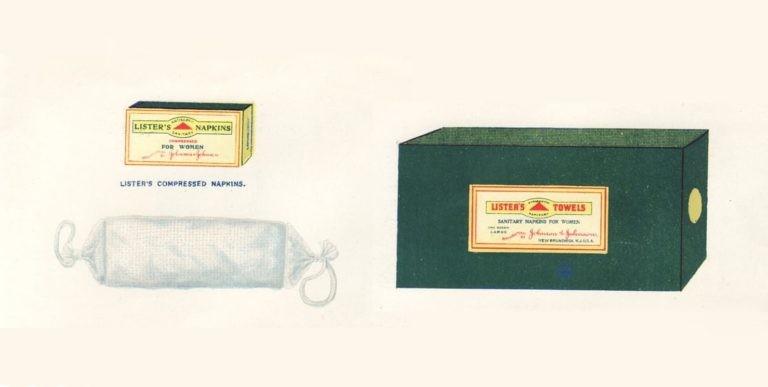

By the end of the century, however, Hartmann in Europe and Johnson & Johnson in the USA launched the first mass-produced disposable pads. Nonetheless, these too failed to gain much popularity. Menstruation was seen as something shameful, which meant that women were afraid to be seen buying such products.

Perhaps the strangest example of this stigma from the same period is the sanitary apron. Except for its thick rubber material, it looks quite similar to the classic kitchen apron. However, instead of cooking, these rubber aprons were used during menstruation – they were tied to the body to protect one’s outerwear from blood stains.9

The beginning of the new century gave rise to a more active role for women in society, influenced by the suffragette movement and the labour shortage caused by the First World War. On the one hand, this change required more effective ways to conceal menstruation, and on the other, more comfortable ways to support women during ‘the red days’. Relying on the past, there were now two important factors that shaped the design of menstrual products: they had to remain unnoticeable and not involve touching the intimate area.

So, the race for the most ‘consumer-friendly’ menstrual product began, with its first innovator Kotex and their 1921 campaign Ask for them by name. By marketing menstrual pads under the name of the brand, the initial fear of buying menstrual products was eliminated and it gradually became a common practice among women. Kotex’s popularity was further enhanced by other aspects. First, their products were created from cellulose wool10, developed for the First World War as more absorbent than the previously used cotton, thus providing more secure and longer-lasting protection. On the other hand, Kotex’s branding focused on the ‘modern woman’ who needed to conceal her ‘dark and shameful secret’ from men.11

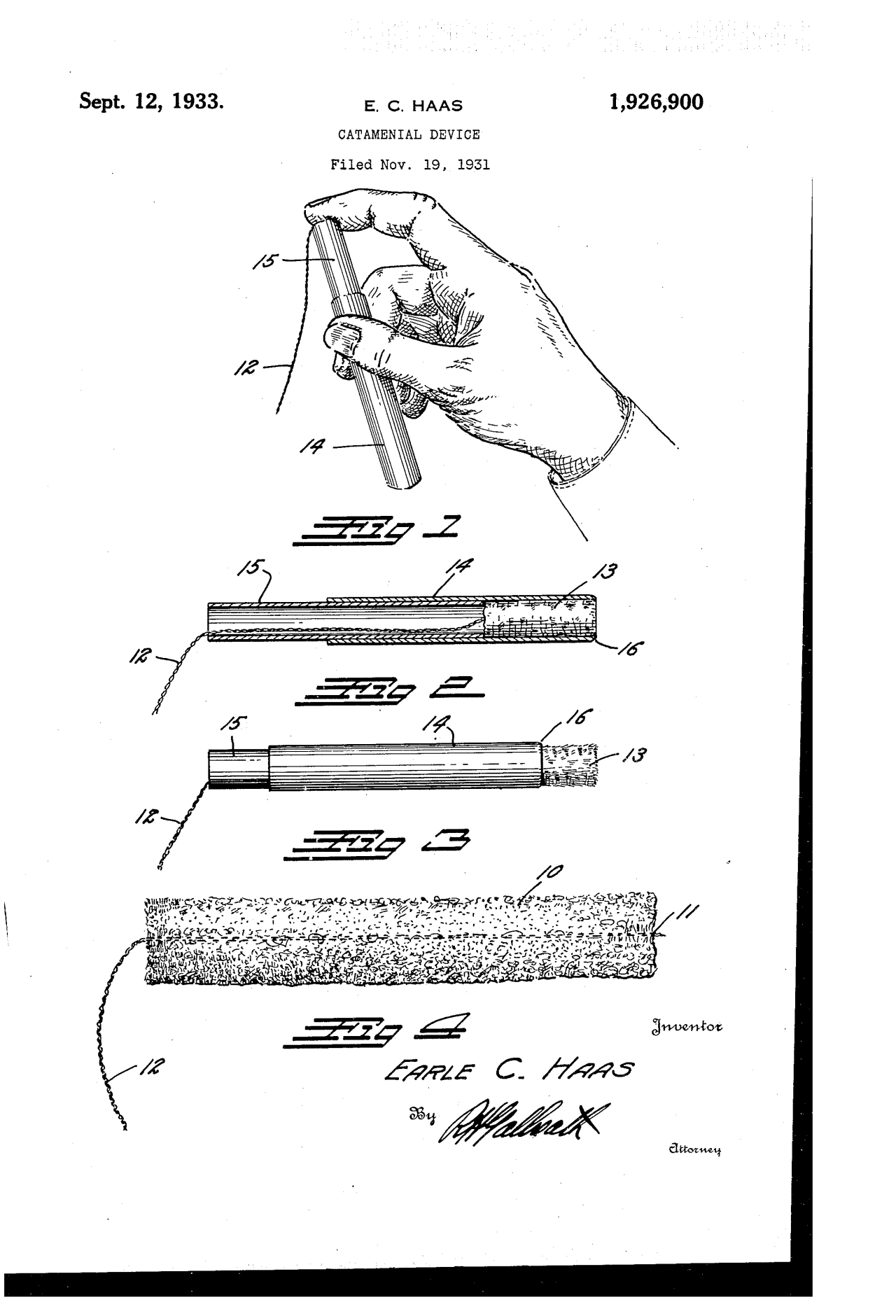

A few years later, the first tampons entered the market. Although their compact form made it easier to conceal them, they were also met with a lukewarm reception. First, there was concern in Catholic circles that using tampons would rob young women of their virginity, followed by the societal fear that inserting and removing the product might provide women greater sexual pleasure than being with their husbands.12 The already absurd compilation of various prejudices was accompanied by the general belief that touching one’s private parts was inappropriate. However, in 1931, Dr. Earle Haas found a solution to this problem by creating a (cardboard) applicator tampon13, the rights to which were soon purchased by Tampax.

Kotex and Tampax, and their approach to the menstrual taboo, also dominated the next century. The use of disposable menstrual products became more and more popular, the menstrual industry increased, and new competing companies entered the market. Although the fear of buying and using menstrual pads and tampons was eliminated, it did not really change the widespread perception that menstruation was something abnormal.

I’LL TAKE A FEW STEPS. SEE IF YOU NOTICE ANYTHING

While Western women were hiding tampons and menstrual pads deep in their palms when going to the toilet, the Soviet woman worried about whether she had anything at all to use for her period.

‘We crumpled up newspapers and stuffed them in our pants. As even toilet paper was not available. What else? Ragged T-shirts, worn-out Marat underwear, old tights that couldn’t be repaired anymore – anything that was seen even remotely usable was brought into play,’ an acquaintance told me, when asked about Soviet menstrual pads.

The Soviet economy was known for its lack of supply – only essential consumer goods to cover basic needs were available in stores, and even they were in short supply. Menstrual products were not seen as essential goods, which prompted women to be resourceful in order to conceal their periods. The list of ‘menstrual pads’ described above is a good illustration of this, yet these kinds of examples still live on only in the memories of people of that time. There is very little reference in the official history of the Soviet Union to menstruation and ways to cope with it.

That is why I mostly rely in this part of my article on the recollections of people who lived during the Soviet period. A couple of days ago, when I phoned my father, he recalled a story of an old girlfriend who used a mattress from a doll’s bed for menstruation. When it comes to my mother, her classmate’s mum sewed patches for her out of unused fabric scraps in exchange for Russian lessons she gave her daughter.14 Through acquaintances, gauze and cotton wool were sometimes obtained from hospitals, and then economically used for menstruation.15 One of the key words that also emerges from the conversations is ‘reuse’ – everything that could be washed was washed and used again, including the cotton wool and gauze that were originally designed to be disposable.

At first, these stories might sound slightly amusing, but this perception is quickly replaced by bewilderment and anguish. Nonetheless, the people with whom I discussed the menstrual arrangement of the Soviet era seem to have almost forgotten all about it. At the time, they didn’t think much of the lack of menstrual products, as it was part of the daily life of the Soviet woman.

The Soviet woman was considered strong, independent and hardworking – she managed to combine work and family responsibilities perfectly and without complaining. Among other things, this meant that menstruation and the accompanying pains or mood swings were considered petit bourgeois.16 When we put this together with the pro-natalist attitudes prevalent in the Soviet Union17, which meant that family policy was centred on increasing the number of births, the picture of why menstruation was so stigmatised and why menstrual products were not considered important enough to be seen as essential consumer goods, gradually becomes clearer. However, the taboo didn’t only result in the lack of menstrual industry, but the effects also extended to the insufficiency of available information. Most of the information concerning menstruation was gained from female friends and close relatives; the few rare publications on menstruation described it as something that should not have any effect on a woman’s daily life.18

In real life, however, it affected women significantly, making them stressed and insecure. Periods did in fact seem impure, as the homemade ‘products’ of questionable quality started to smell after long periods of use. It was also common that menstrual blood seeped through their outer clothing, which meant that the phrase ‘I’ll take a few steps. See if you notice anything’ became common among female friends. Though leakage was quite common, it did not mean that you would not be publicly humiliated for it.19

One of the people I interviewed pointed out industrial diapers, which found their way into people’s homes during perestroika, as the first sign of any alleviation, and which were then sparingly used also for menstruation. When Estonia regained its independence and the quantity of imported goods increased, the first disposable menstrual pads also arrived from the West, but due to high prices20 and old habits, the former Soviet woman didn’t really latch onto them in the beginning of the 1990s.21 However, the improved quality of life in the years before the turn of the century, caused more and more women to discover the advantages of Tampax and Always.

CARE FOR MOTHER EARTH

The new millennium demands new products, and the increasingly distressing effects of global warming are also pushing the menstrual industry to come up with more sustainable consumer goods. One of the pioneers here was The MoonCup®, the first reusable medical-grade silicone menstrual cup, launched in 2002. Its success on the market is primarily due to the new material – the use of silicone allows the product to be inserted and used comfortably, and the material is also suitable for women with latex allergies. From the point of view of stigmatisation, it is perhaps even more important that the product’s design took a firm stand against the shaming of menstrual blood, even though only among women using the product. The deliberately transparent design allows for the menstrual blood inside the cup to be seen when the product is removed, and upon usage, it stains the light-coloured silicone, leaving visible blemishes even after washing.22

Today, one can find in stores and online several reusable alternatives to menstrual products. So why is it still worth talking about the impact of stigmatisation on production?

The persistent taboo surrounding periods has for a long time brought a narrow view of the products. It is accepted that women’s health is being monetised, but research into the broader impact of menstrual products has remained superficial. For example, we are still unable to say for sure how much blood a menstrual pad or tampon can absorb because due to the stigma surrounding menstrual blood, these products have only been tested with an unspecified blue liquid.23 This is important to know, however, as tampons with higher absorbency can cause life-threatening toxic shock. Also, this year, scientists from several US universities found 16 different metals from tampons, their packages, and applicators, many of which are toxic and can cause cancer.24 In addition to the already known chemical substances, such as semi-synthetic viscose, which is used for greater absorbency, and various fragrances, according to recent studies, both menstrual pads and tampons contain a large amount of macro- and nanoplastics.25

The irony of the whole story is that alternative and reusable products have been within women’s reach for over a century. From the late 19th century until the 1980s, reusable menstrual pads, which were mostly attached to the body with a sanitary belt, were on the market. They can be seen as the forerunners of today’s menstrual pants. The first menstrual cup that became a consumer good, the Tass-ette, dates back to 1935 and looks identical to the MoonCup, but instead of silicone, it is made of rubber.26 In addition to the menstrual taboo, the shortage of rubber at that time was partly responsible for the ill fate of the product. It was relaunched 20 years later, but due to poor sales figures this attempt also failed.

The practices caused by the menstrual taboo continue to this day – tampons and disposable pads are still the most purchased menstrual products.29 However, this comes at the cost of women’s health30 and the environment.

Production is often accompanied by hidden (and not always favourable) values and risks. This text might be a good illustration of why the primary values of product design – function and user comfort – are often not enough. The more we discuss menstruation and menstrual products, the faster we can move towards a world that is safer for both ourselves and the environment. Until we are still stuck in old stigmas, either consciously or unconsciously, the number of sufferers remains invisible and their extent unknown.

References

- Aristotle refers here to the Pythagorean Table of Ten Opposites. On one side of the table are concepts such as: finite, odd, one, right (direction), male, rest, straight, light, good, square. And on the other side their opposites: infinite, even, many, left, female, motion, curved, darkness, evil, oblong.

- Aristotle, ‘Metaphysics’. The Complete Works of Aristotle, 11 [986a-986b]; and ‘Generation of Animals’. The Complete Works of Aristotle, 45 [738b] (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1991).

- J. Butler, Bodies That Matter (London: Routledge, 1993).

- J. Delaney, M. J. Lupton & E. Toth, The Curse: A Cultural History of Menstruation, rev. ed. (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1987).

- Luteal phase is the final phase of the cycle, when the woman’s body prepares to release the unfertilized egg. During this period, women may experience PMS (i.e. premenstrual syndrome).

- A. Bhartiya, Menstruation, ‘Religion and Society’, International Journal of Social Science and Humanity, Vol. 3, No. 6, November (2013), pp. 523–527.

- The simplest translation for this might be a ‘menstrual bag’.

- S. L. Hockert, U.S. Patent 70843, issued November 12, 1867.

- H. Finley. Menstrual Sanitary Aprons, Underpants, etc. in Mail-Order Catalogs from 1918– 1941 (U.S.A.), The Museum of Menstruation and Women’s Health <http://www.mum.org/sanapron.htm> [accessed 21.10.24].

- Cellulose wool, a natural substitute for cotton, was developed in 1914, and used by Kotex’s parent company, Kimberly-Clark, during World War I to produce bandages for the US Army.

- D. Linton, Men in Menstrual Product Advertising – 1920–1949 (2007), p. 100.

- S. L. Vostral, Under Wraps: A History of Menstrual Hygiene Technology (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2008).

- Dr. Earle Haas, U.S. Patent 1926900, filed November 19, 1931, issued September 12, 1933.

- This was a rare exception, however. High-quality fabrics were in short supply in the Soviet Union which meant they were not readily used for periods.

- Anonymous interview, October 12, 2024.

- P. Vasilyev, ‘Re/Production Cycles: Affective Economies of Menstruation in Soviet Russia, ca. 1917–1953’, Body Politics, 8, Heft 12 (2020), pp. 62–69 <https://doi.org/10.22032/dbt.51646> [accessed 21.10.2024].

- Chris Burton, ‘Minzdrav, Soviet Doctors and the Policing of Reproduction During Late Stalinism, 1943–53’, Russian History (Summer 2000), pp. 197–221.

- Y. Karpova & P. Vasilyev, ‘Medicine on Russian-Language Social Media’, The Rowman & Littlefield International Handbook of Bioethics, ed. by E. Di Nucci, J.-Y. Lee, I. Wagner (Rowman & Littlefield Publishers, 2022), p. 352.

- Symbiosis of interviews, 12.–14.10.2024.

- Ibid.

- P. Vasilyev & A. Konovalova, ‘Changing Menstrual Habits in Late 20th- and Early 21st-Century Russia’, Open Library of Humanities 9 (1) (2023), p. 10 <https://doi.org/10.16995/olh.6352> [accessed 21.10.2024].

- C. M. Røstvik, SAFER, GREENER, CHEAPER: The Mooncup and the Development of the Menstrual Cup Technology in the Twentieth Century (2021), p. 95.

- E. DeLoughery, A. C. Colwill, A. Edelman et al., ‘Red blood cell capacity of modern menstrual products: considerations for assessing heavy menstrual bleeding’, BMJ Sexual & Reproductive Health, Vol 50 (1) (2024), pp. 21–26 <https://doi.org/10.1136/bmjsrh-2023-201895> [accessed 21.10.2024].

- J. A. Shearston, K. Upson, M. Gordon, V. Do et al., ‘Tampons as a source of exposure to metal(loid)s’, Environment International, Vol 190, Aug (2024) <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.envint.2024.108849> [accessed 21.10.2024].

- L. P. Munoz et al., ‘Release of microplastic fibres and fragmentation to billions of nanoplastics from period products: preliminary assessment of potential health implications’, Environmental Science: Nano, 2 (2022) <https://doi.org/10.1039/D1EN00755F> [accessed 21.10.2024].

- L. W. Chalmers, U.S. Patent 2089113, filed 11.07.1935, issued 03.08.1937.

- Photo found here: <http://www.mum.org/washge35.htm> [accessed 21.10.2024].

- Advertisement found on this page: <http://www.mum.org/CupPat1.htm> [accessed 21.10.2024].

- Harvard Chan, ‘Menstrual hygiene products: pads and tampons are the go-to choice’ <https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/applewomenshealthstudy/updates/menstrualhygieneproducts/> [accessed 21.10.2024].

- Although reusable and eco-friendly menstrual products are considered safer, they too need to be used with consideration. For example, the menstrual cup can also cause toxic shock if worn for too long at a time. Two companies producing menstrual pants (Thinx and Knix) are facing lawsuits after chemicals (PFAS) were found in their products.