Published on

25.11.2022

Kristi Kuusk is a designer-researcher working on the direction of crafting sustainable smart textile services. She explores new ways for textiles and fashion to be more sustainable through the implementation of technology. Today Kuusk works as a senior researcher in textile futures at the Estonian Academy of Arts running the Sensorial Design project.

kristikuusk.com

Nesli Hazal Oktay is a designer-researcher and educator focusing on the impacts and interactions emerging technologies could deliver. Since the 2019/20 academic year, she has been working as a visiting lecturer and also as a curriculum developer for the Interaction Design MA at the Estonian Academy of Arts. Oktay is also a doctoral student at the Academy where she is investigating how design placebos can extend the sense of empathy in digital natives when dealing with videotelephony.

neslihazal.com

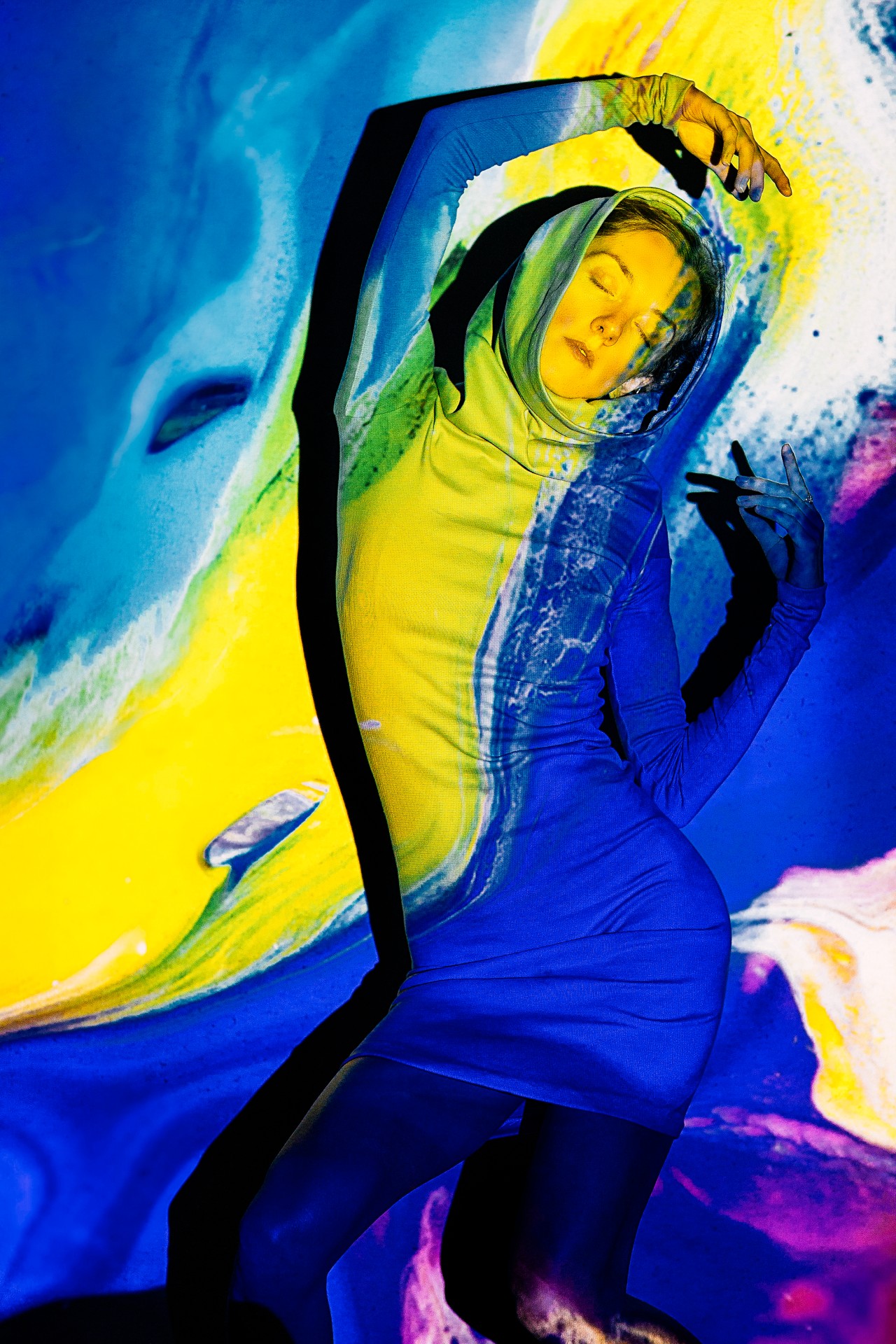

Arife Dila Demir is a junior researcher and doctoral student at the Estonian Academy of Arts (EKA). Her research interests include soma design, somaesthetics, aesthetics of bodily engagements, movement-based interactions, interactive textiles, critical and speculative design. Demir worked as an e-textile costume designer for a project executed between an artist and Tallinn University funded by Vertigo STARTS Residency (2019–2020).

dilademir.com

We see sensorial design as a design approach that aims to design embodied interactions considering humans as sensory beings as a combination of the mind and body. Therefore, it is designing with/for/through the sensory body extending further from the classic five senses. It includes the sense of space, sense of movement, sense of pain etc. In the phenomenological account, the sensory body is referred to as the ‘lived body’ through which humans experience the world and themselves; hence, making

For us, sensorial design means making an intimate connection with the body, finding new ways of communicating and moving with it; thus, cultivating careful practices of being in the world through moving and sensing bodies. Therefore, we suggest that such a design process should start with the moving body, as movement is the way of being and interacting with the world and

Movement-based thinking in interaction design has been applied to trigger imagination in the design

Neuroscientific insights show that our understanding of ourselves and our body is in constant change. It is updated in real-time. The work of Ana Tajadura-Jiménez et al. explores how multisensory-based interaction technologies could be used to alter people’s perceptions of their own body, their emotions and behaviour. Using this notion, we can potentially ‘trick’ ourselves by altering our sensory input, and as Tajadura-Jiménez shows, change our behaviour through

Magic

Clothing and accessories such as suits, high heels, corsets, miniskirts and gloves have influenced people’s self-perception all along. On the one hand, they alter the wearer’s posture and gesture physically, on the other hand, they create a certain visual appearance. Opening new ways to change self-perception through technology interacting with the body allows the trigger of the sensation to be in constant change. For example, the same clothing could invite the wearer to feel excited in one minute, and calm half an hour later. However, the suit is not changed for the sweatshirt meanwhile; therefore, the change is not visible to external viewers. Of course, many aspects, such as the long-term use of this kind of stimulation, as well as digital safety and privacy issues, need to be considered along with material sustainability when developing the project further.

By creating novel material concepts for realising projects with unique needs, the researchers push the boundaries of traditional disciplines. The formerly well-defined areas of knowledge extend, collaborate and even merge into new sub-disciplines, such as e-textiles (textiles + technology). Technology combined with textiles opens up a whole space of opportunity for playing with the senses very close to our bodies. As we discussed previously, sensorial design is not only interested in the five senses but also works with the kinesthetic senses, sense of proprioception, sense of pain etc.

Squeaky/

Squeaky/Pain explores how chronic pain experiences may inform the design of wearable interactive artefacts, called soma extensions, for sensory bodily awareness. As close-to-body artefacts, soma extensions mediate sound-motion interaction. The artefact mediates two sounds (1) the disturbing sound of a squeaky wood that represents the agony of pain, and (2) a pleasant atmospheric sound that represents the relief from pain. There is no way to turn off the sound but by moving extremely slowly, the wearer can keep the volume of the disturbing sound down and keep the volume of the pleasant sound high. Through transferring the qualities (both agonizing and pleasing) of pain, a soma extension is designed to augment the wearer’s sensory awareness of pain through a movement-based interaction.

When moving, sensory bodies form spatial qualities, for instance, when bending forward they form curvy qualities. On the other hand, bodily movements always happen in relation to spaces that they exist in and the proximity of the other animated or non-animated beings that co-exist in the same place. In terms of human-to-human interaction, videotelephony has brought great improvements in communication possibilities by overcoming the limitations of time and space. However, they have also modified the perception of bodily movements, those related to the sense of proprioception, and the sense of vision, which is limited to a quasi-two-dimensional perception.

Empathic

Empathic placebos explore the potential that movement-based interactions can deliver in video telephony. Despite the virtual closeness in video calls, the potential use of the tactile channel is limited. Consequently, the more digital videotelephony enters the lives of people, the less room there is for the sensorial interactivity and bodily interactions usually associated with empathy. As wearables focusing on bodily awareness in video calls, empathic placebos invite digital natives to be more in contact with their bodies so that they have more chances to shape their experiences with their loved ones and themselves. Empathic placebos limit the bodily movements of wearers as an attempt to turn the familiar upside-down as a way to disrupt habitual perceptions and ways of thinking – or in this case, feeling, moving and interacting – in video calls.

Based on our understanding of sensorial design, we envision future bodies that are intimately connected with the possibilities of sensory interactions. Our practice-based work invites the viewer to reflect – What if our clothes could support us in feeling how we would like to feel for a certain situation: more confidence for a work occasion, more energised for training, calmer for resting? What if instead of 10 outfits we just needed 1 because external looks would be less relevant than the tactile patterns we embody? We wonder how close-to-body applications of e-textiles may support humans in connecting with their inner happenings such as pain. And how can we design better engaging close-to-body artefacts that can be adjusted according to the needs of each body? We ask how design objects can support the creation of bodily interactions during videotelephony for digital natives who are close by heart but physically apart. How could design placebos extend the sense of empathy among digital natives during video telephony? By asking these questions through our prototypes, we envision alternative futures in terms of feeling, moving and interacting.

References

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty, Phenomenology of Perception: An Introduction. (Routledge, 2002).

- Maurice Merleau-Ponty; Maxine Sheets-Johnstone, The Primacy of Movement (Expanded 2nd Ed.), (John Benjamins Pub. Co., 2011).

- Maxine Sheets-Johnstone.

- Danielle Wilde, ‘Extending Body and Imagination: Moving to Move’, International Journal on Disability and Human Development, 10, 1 (2011) <https://doi.org/10.1515/ijdhd.2011.004>.

- Kristina Höök, Designing with the Body: Somaesthetic Interaction Design, (MIT Press, 2018).

- Lian Loke and Toni Robertson, ‘Moving and Making Strange: An Embodied Approach to Movement-Based Interaction Design’, ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction, 20, 1, (2013), pp. 1–25 <https://doi.org/10.1145/2442106.2442113>; Kristina Höök.

- Ana Tajadura-Jiménez, Maria Basia, Ophelia Deroy, Merle Fairhurst, Nicolai Marquardt, and Nadia Bianchi-Berthouze, ‘As Light as Your Footsteps: Altering Walking Sounds to Change Perceived Body Weight, Emotional State and Gait’, In Proceedings of the 33rd Annual ACM Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, (Seoul Republic of Korea: ACM, 2015), pp. 2943–2952 <https://doi.org/10.1145/2702123.2702374>.

- Kristi Kuusk, Ana Tajadura-Jiménez, Aleksander Väljamäe, ‘A Transdisciplinary Collaborative Journey Leading to Sensorial Clothing’, International Journal of CoCreation in Design and the Arts, (2022) <https://doi.org/10.1080/15710882.2020.1833934>.

- Arifa Dila Demir, Nithikul Nimkulrat and Kristi Kuusk, ‘”Squeaky/Pain”: Cultivating Disturbing Experiences and Perspective Transition for Somaesthetic Interactions’, Diseña 20, (2022).

- Maxine Sheets-Johnstone.

- Paolo Paradisi, Marina Raglianti and Laura Sebastiani, ‘Online Communication and Body Language’, Frontiers in Behavioral Neuroscience, 15, (2021) <https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2021.709365>.

- Nesli Hazal Oktay, ‘Design Placebos for the Impossibility of Empathy in Videotelephony’, in proceedings of DRS2022: Bilbao, ed. by D. Lockton, P. Lloyd and S. Lenzi, (Bilbao, Spain, 2022) <https://doi.org/10.21606/drs.2022.598>.

- Marc Prensky, ‘Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants’ Part 1., On the Horizon, 9, 5, (2001), pp. 1–6 <https://doi.org/10.1108/10748120110424816>.