Published on

25.11.2022

Darja Popolitova is a contemporary jewellery artist. Her process is driven by an ironical view which fuels her interest in blending digital craft and video performances with fiction. Popolitova finds jewellery’s haptic and symbolic nature a generous medium that allows her to conceptualise ideas. Currently she is completing her doctoral studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts.

instagram.com/darja_popolitova

Juss Heinsalu is an artist, lecturer and head of the Design and Crafts curriculum at EKA. His autonomous research-based creative process explores the embodiment of life in clay, merging scientific hypothesis, mythological and ethnographic knowledge with material-based studio practice – by creating a series of speculative conditions that present alternative mineral-based lifeforms.

jussheinsalu.eu

Sandra Kosorotova is an artist and designer from Tallinn, Estonia. In 2020 she established an open garden near Narva Art residency called Kreenholm Plants. She is currently on a residency at WIELS (Brussels). Kosorotova has often worked with textiles, text and plants, using surplus and safely biodegradable materials to make art objects that also have a potential practical application: can be worn, consumed as food or used as medicine.

sandrakosorotova.com

Taavi Hallimäe is a lecturer at the Estonian Academy of Arts and the editor-in-chief of Leida. He has a master’s degree in cultural theory and philosophy from Tallinn University (2019). Currently, he is a doctoral researcher at the Institute of Art History and Visual Culture.

The pandemic that started in 2019 gave the majority of the world a good reason to move massively onto various virtual environments. This initiated three Estonian artists working with material-based creative practice – Darja Popolitova, Juss Heinsalu and Sandra Kosorotova – to hold a discussion on their creative work connected to various technologies and materials. At the same time, they contemplated the most important aspects in their creative practice and analysed how these principles were adjusted to suit the environmental and technological changes. Questions were asked by Taavi Hallimäe.

Taavi Hallimäe: We first planned to gather this discussion group more than a year ago when we had to talk about the pandemic and how this had influenced artists with a material-based creative practice. At the present moment it seems that meanwhile things have changed, and the pandemic seems to be a worn-out issue. How has the pandemic influenced your artistic practice?

Darja Popolitova: I faced problems when writing my doctoral thesis since this kind of work requires a specific timeframe. I began writing it in 2017 and when the pandemic started, I had to somehow find my way since the era was directly related to the use of screens. Everything, including academic studies took a digital form. Eventually there were so many screens that one could but sit in front of them. And then the war started, this being another context I have to take into consideration in my thesis. Both the pandemic and the war in Ukraine are related to the concepts of ‘closeness’ and ‘alienation’, and inevitably refer to our so-called tactile zone.

TH: We get information about Ukraine mainly through screens. We may have met someone from Ukraine but we don’t have a direct experience of the war. Sandra and Juss, did your artistic practice gain from the pandemic or was it the other way round? Should the pandemic be discussed rather in the context of material?

Juss Heinsalu: In my artistic practice, I use quite a lot of technological means, mainly based on how technology as a tool helps us to get closer to a specific material. The pandemic has instead revealed the need for direct physical contact. Whereas Darja mentioned the aspects of closeness and alienation, I am intrigued whether it is possible to digitalize this so-called tangibility. Should it be done at all, and if yes, then to what extent? The hybrid meetings and digital learning that have often been favoured seem in contrast exhausting and distancing. I find it funny that we experience both ‘worlds’ through our fingertips.

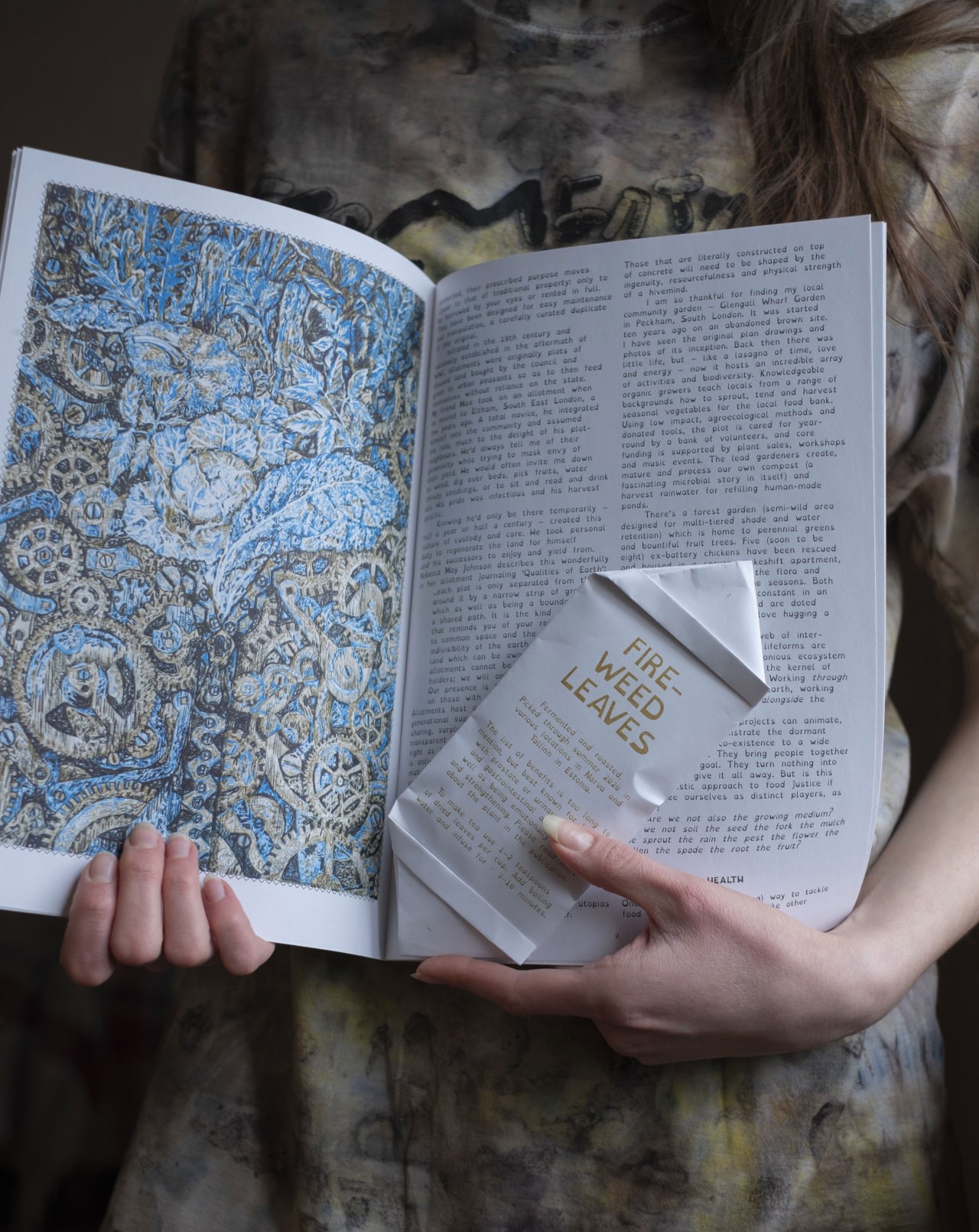

Sandra Kosorotova: I remember that the last thing I did before the pandemic was a series of workshops. It was impossible to continue doing these during the pandemic; the whole thing has definitely influenced my creative practice. Juss mentioned tangibility – I also missed it a lot during the pandemic. It was probably the reason I started to work more with plants, to grow and collect them. I felt it was helping me so much and I wanted to share this skill. I established a community garden in Narva where I also held weed tours. I found a way to work with the themes that are important for me in the open air. One project that was more directly influenced by the pandemic is the WEEDS FEED care package – a care package with a book and a bundle of herbal teas, available to order for free. It was then sent directly to one’s mailbox during the harshest time of the lockdown. I designed the book so that it would be comfortable to read in bed while sick. All summer I have been collecting and processing the herbs for the teas. With this project I searched for ways to achieve both a tactile and bodily experience as an artist and as a person encountering art during the period of restricted physical contact. Another artwork that was put together during that period was Occupatient – a piece of a garment with a therapeutic effect, using the Ayurvastra technique of delivering medicine through clothes dyed with healing plants. Its zero waste cut is reminiscent of the uniform worn by patients or doctors. The costume is embellished with spells.

TH: Many people who did not value contact with other people, physical objects or practices before the pandemic, discovered the necessity of the tactile experience during the isolation. Is tactility a mandatory way for material-based artists in order to experience the world?

JH: This is certainly an important aspect. Perhaps it is something that cannot be conveyed without a form of co-activity, co-creating or testing something together, as it can often be observed in Sandra’s practice. And on the other hand, you are right, Taavi, to state that touch is the most essential thing in a creative process, without it, nothing would happen. And at the same time, I am also thinking of how Darja’s artistic practice is shaped without direct manual intervention; or how several contemporary ceramicists work digitally and finalise their forms by using 3D printing. However, I’d like to believe that when using only technological means to achieve the result, one has to have an experience and awareness of the specific material – one has to have acquired the tactile knowledge beforehand. For instance, non-ceramicists seldom take gravitation into account. They may have a draft or a model for printing, but the printed object cannot always meet the author’s expectations since it may deform due to its own weight. A ceramic object shrinks and moves even more in the kiln. An experienced craftsman can forestall these effects. It can also be compared to cooking – everything cannot be written down in the recipe. The consistency of a dough can be eventually defined only by personal intuition. If the four of us would meticulously follow the same instructions and use the same ingredients, it would still result in four pastries each with entirely different texture, taste and appearance. Such perception is based on the experience of accumulated contact and on skill or the lack of it.

TH: Darja, perhaps you would tell us about your work in the context of tactility.

DP: One of the objectives of my doctoral thesis is to work with tactility; however, through this I am talking about the phenomenon in life in general. For me, tactility is not only direct contact between skin and an object, it is something that connects the so-called touching the skin, but also kinetic and proprioceptive qualities. The experience of being in front of screens is bodily and tactile – something is in front of you and happening to you, something is invading your body and going through it. Tactility can be compared to a frame rate, a structure or modularity through which we experience the world.

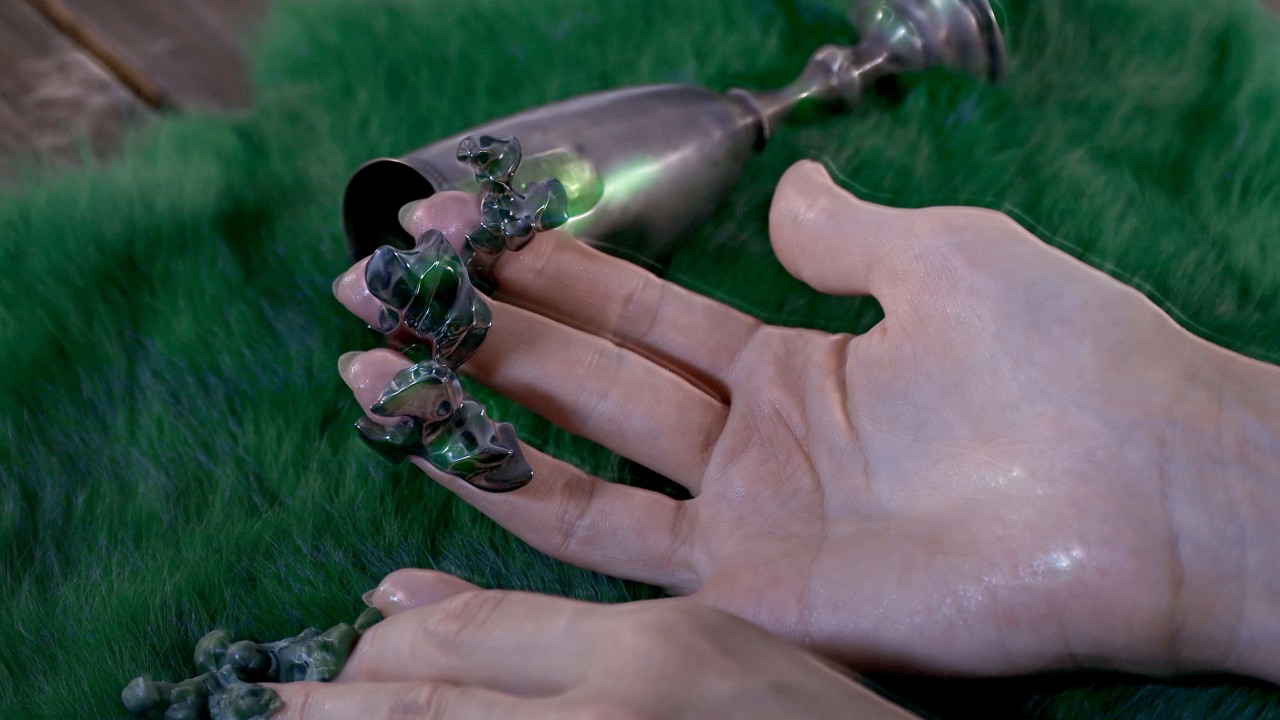

I divide my work process into two: one aspect is the process-based experience between myself and the art object – that happens during working and when the object acquires a form, through the choreography of my hands and depends on the way my gestures in my studio have been built up. Also, what touching the material as well as my grasps will do with my body. The way I use the 3D software, how I zoom out from my 3D-object. When we deal with physical materials then we know the weight, as was also pointed out by Juss, using gravitation as an example. With computers we also have a certain interface, there is a mouse and a screen. This is our territory of work and perception. It is a topological process taking place in a specific place at a specific time – buttocks on a chair, a sweaty hand touching the mouse and then also myself, experimenting with the forms.

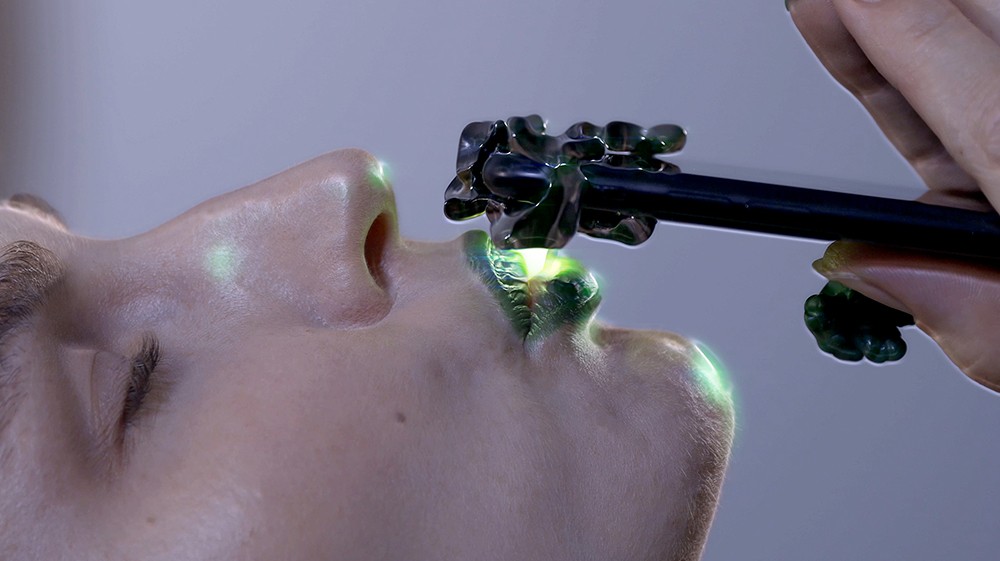

Another aspect lies in the tactility between the spectator and the art object – how the audience perceives something that I have displayed in the exhibition space. Interviews held for my research – namely, the parodies of interviews – convinced me that people in the gallery experienced my works through their bodies. In order to describe the works they used words with material connotations, for instance ‘rough’ or ‘smooth’. The way the witch Séraphîta touched jewellery on the screen seemed ‘spicy’ for some spectators. Descriptions with emotional or physiological characteristics were also used – for some people, the artworks were either funny or sad, someone was crying or laughing. Thematically synchronized descriptions were used as well, referring especially to irony and humour. The experience of watching a video can be described with a certain lexicon that is formed by our experience of life and our contact with objects and materials. We have once experienced it and now using this experience to describe something else.

TH: And somehow, we could also state that we live and experience the world through certain metaphors. Just like our thinking is related to language, we are also influenced by physical senses. The emotion that we get from watching Darja’s videos is eventually directed by Darja herself. The purpose of this is to highlight specific impulses in spectators since the artist is aware that our way of perceiving the world can only happen through some filters. Sandra, can you add anything to what Darja and Juss just said?

SK: To answer your initial question, whether tactility is the most important aspect in my creative practice: I agree that it is quite important. I started my artistic practice with digital printing on textiles. Other people were printing and sewing the work for me, while my own contribution was the idea, a draft, a digital file. At some point I realised that I lacked sufficient physical contact and changed the way I worked. Now I only undertake projects that I can make all by myself. Crafting brings me joy and a feeling of satisfaction.

TH: If I try to position the three of you as artists then it seems that all of you create artwork that is accompanied by some kind of a complement – Sandra, in your case it is text or community, Juss has natural sciences and Darja’s work is complemented by visual culture as well as representations of social phenomena or values. How did you find your complement?

DP: You mentioned metaphors – I’d like to answer your question using the same concept. For me, the creative process is something that remains hidden behind the completed object – the polished and clean artwork – for the spectator. As also Sandra said, the creative process can certainly be in the focus of the artwork and it can be exhibited in the gallery. But for me, the creative process is a metaphor, a very complicated and confusing metaphor. Both creative practice and the artist’s identity are great metaphors that are made of tiny elements which are hard to define under the magnifying glass, even if artistic research is exactly what focuses on it.

TH: On one hand, we can talk about developments and themes within research – and one will reach these through a more or less natural process. And yet, this also requires moving from your initial knowledge, skills, technologies and materials to some place new that may become entirely different for the artist as well as creating new impulses. In my opinion, Darja is not only an artist but someone who studies and practises visual culture in a wider meaning. In this case, how should one maintain the relationship with the material?

DP: I think that it is unnecessary to maintain the relationship – it must be extended. Here lies the freedom. I guess I even irritated my supervisor who told me to finally decide whether to be a jewellery or a performance artist. There are just so many elements in my artistic practice. It’s a mess. But I tried to find the associations and in my opinion, it is essential to play and to create, to map the uncharted territories, to extend, change and create monsters. I like the idea – to create a monster. To create something that is made of various organs but which eventually becomes one organism attempting to perceive its body in some way, to learn how to walk again with its new body.

TH: It seems that no matter how we translate the concept of craft, it still represents an unnatural peripheral form that is extremely intriguing for me. Artists whose practice has grown out of craft have an interesting, even shifted approach towards the themes that have been either neglected by contemporary art or the approaches have been too predictable. Just like the uncharted blind spots. Juss, what is your connection to chemistry or the natural sciences? Why do we see this in the background of your artwork?

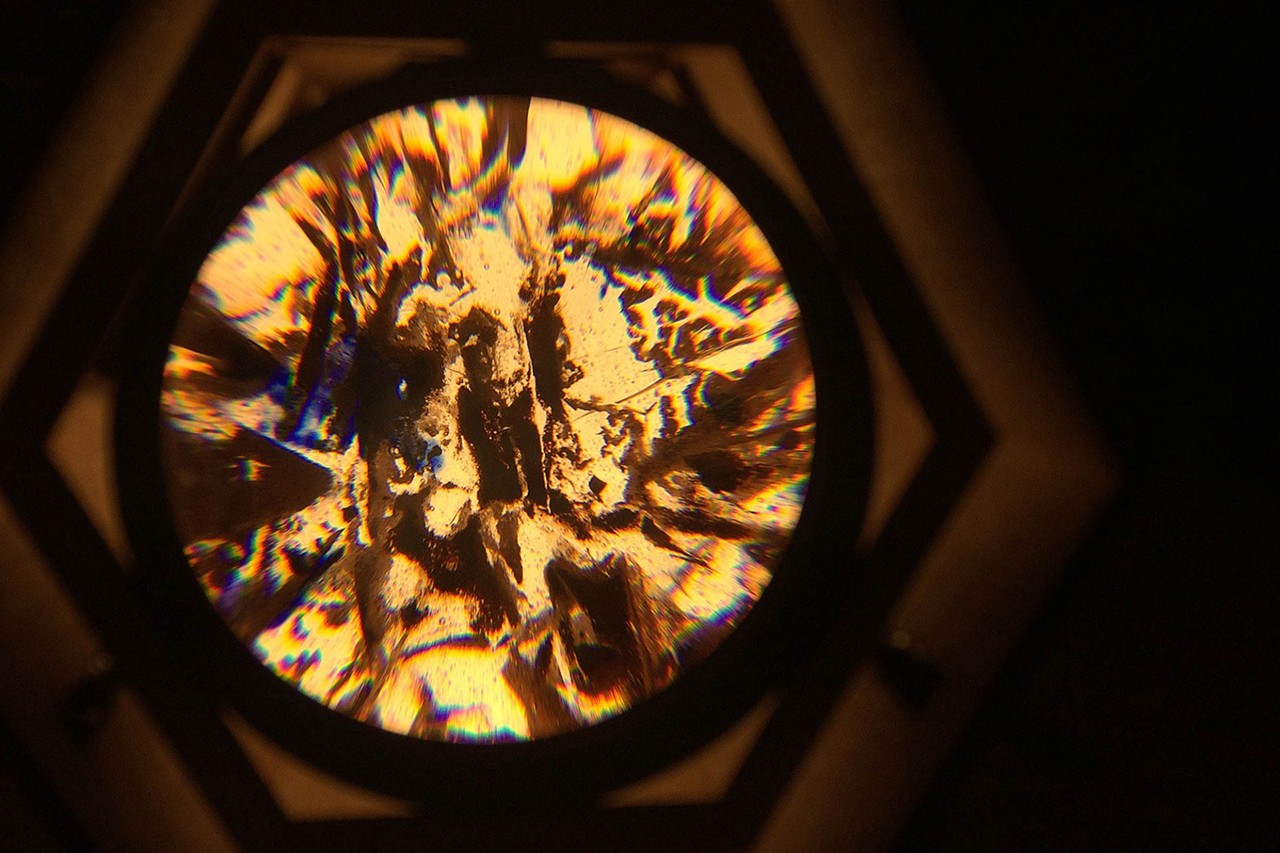

JH: The first question is easy. And Darja should know it especially well right now since it is our objective in the studying process to learn where certain impulses come from. When I was at the end of my MFA studies, I was asked the following question more than once: where do the aesthetic choices come from that characterise my artwork? Suddenly, I began to see the connections between my artistic practice and scientific apparatus as well as the visual language – something I was in contact with in my childhood. Looking through the microscope, all kinds of illustrated books, charts, graphs, growing up in a family of geologists – all this developed the way I look and see. Unconsciously, it has always influenced the way I compose and work as an artist. Today, I am consciously amplifying these elements, as well as questioning them more closely. How come we recognize it? Where do the so-called scientific aesthetics come from?

My interest in an approach based on material research comes from simple curiosity. And on the other hand, there is something philosophical and existential in it. I already knew long ago that I am rather an observer and not a maker type. When working with materials and observing certain reactions, outcomes, or by alchemically mixing together various things, I somehow examine the world and try to understand the rules or principles in the universe.Perhaps we could take a much more active role in this process in order to consciously recreate all this. It has also been a conscious choice to be an artist and not a scientist for a clear reason – I can have considerably more freedom to practise on the frontiers of art and science. Perhaps such art does not stand alone after all. The natural sciences remain in relation to it, as such art uses a form of scientific language. The speculative qualities I am most interested in are always translated through other fields. In a way, we deal with the same metaphorical aspects that were mentioned before.

DP: If you say that you come from the family of geologists then in my opinion you are talking about autobiographical influences that can also be related to tactility. This is a tactile view of yourself – and everything that had an effect on you in your childhood.

JH: I’d like to add that in ceramics, many things take place due to the heat in the kiln. This is the part that cannot be touched. Paradoxically, we create work with our hands, and yet, there is something else that is untouchable. As for ceramics, it was before my studies at the Estonian Academy of Arts when I experienced an epiphany in the wood-fired kiln. One could peek inside and see how clay transforms into ceramics. Perhaps similar to this process there have always been some kinds of phenomena or conditions that have been enchanting for me, that cannot be touched by hand. Also, there is this role of a digital or technological mediator, much closer to what the object itself embodies. In my artistic practice I often make optical tools where the material remains accessible only through a lens or a filter. Surprisingly, here I contradict myself, since earlier I have been emphasizing tactility and manual contact. And yet, when the artwork is ready, then for me, its importance lies beyond the object itself, even if it is always returning to clay which is very physical and material.

SK: One reason why text and working with community are elements of my work might be that I find it important that many people could find a way to relate to my art. Adding text can make my work more accessible also to those not fluent in the language of contemporary visual art. When working with a community – for instance leading a public workshop – one can more easily involve people in the art world. I come from a working class family; contemporary art has always been an unknown territory for my parents. When I made art, I always thought how my mother would understand this, am I offering enough various entry points to the work. I am still thinking like this; however, when an artwork becomes too clear, it might lose its attractiveness.

TH: Could you imagine your artistic practice without the additional components? Would material art without any complements be something very archaic?

JH: When I have to identify myself, I would leave out all additional descriptive terms – I prefer to be simply an artist. Perhaps an ‘observer’ is a much more interesting role. The fact that I also make something with my hands is just one way to view it again in a controlled setting or environment. So this is like rehearsing or modelling a bigger world on a reduced scale. I believe this to be the most exciting aspect for me.

There is some kind of attraction or power of presence in material-based art in its purest form – where the material itself opens up something without adding meanings or metaphors – an art form where we observe the act of chemical reactions or explosions captured in material, made visible, recorded, petrified. It simply is without any social or political context. This could be a miniature form of the sublime, experiencing something that can normally happen when for example looking at geological outcrops or a meteorite crater in Saaremaa, where all the layers of rocks have been turned and twisted.

DP: You describe it as an immediate phenomenological experience that is not intellectualized – it is not ‘what?’ but ‘how?’.

I remember when I interviewed the visitors at my exhibition in the gallery, I asked them to describe how the exhibition experience felt or how they lived through the experience. Many people from intellectual fields were inclined to describe their experience through some abstract concepts and terms. I tried to bring them back to the surface of the skin. After all, what was the feeling like? People seem to lack the vocabulary to describe their bodily perceptions. I even made a list so that they could choose the right words. Indeed, intellectualising and conceptualising are something that lead us away from our bodily experience.

I also recalled how I have been looking at how other people work. My father is an applied artist and I remember myself looking at him work when I was a child. As an artist you cannot exit your body in order to take a look at yourself from a different perspective. Another memory is about my father working with wood in his studio – I remember the wood dust flying in the air and the sight was even better in the sun rays falling through the window. I remember how he sharpened his knives and took some gemstone he was polishing. He looked at the patterns and licked them on the stone before placing these into the light that finally brought out the patterns. These were the small things I have remembered as these were connected to bodily choreography in a room and the way materials behave.

TH: In my opinion this is an intriguing paradox that I cannot fully solve myself. Does Western culture, where we are living, prioritise the material or the immaterial? In other words, when we see a gemstone do we think of Darja’s father licking the stone so that some structures would appear, or do we place the gemstone into a specific cultural context in order to understand which values or meanings are referred to with this stone? And sometimes it seems to me that when we are talking about the material itself, just like Juss did, then on one hand, material as such can be either extremely physical – for instance the flow of volcanic lava, and on the other hand, extremely immaterial while bearing the meanings referring to the eternal, primordial or inevitable. There is this strange interwovenness of opposite pairs.

DP: It is a combination of symbols and immediate experience accompanying us when we grow up. When you are a little kid watching lava flow then this is an immediate moment or your personal experience. You don’t know anything about lava and perhaps you don’t even know it can be dangerous.

TH: When we talk about knowledge about a material then what kind of knowledge are we talking about? Is it a cultural knowledge that we also meet in a nature documentary, where nature is highly sacralised and where geological processes are described with a deep male voice who addresses the visual as if from God’s perspective?

DP: Slow motion must definitely be there! (Laughing.)

TH: Yes! (Laughing.) Perhaps this is how we can experience this material, even if we actually experience some kind of cultural value. Eventually, we keep telling these stories through the same metaphors and imagery.

JH: Darja described wood dust in the sunlight. Is this the dust we are looking at or are we becoming aware of the light through this dust – experiencing the light as material? Light as a material or an experience finally leads us to the understanding that art is also something that we most of the time are looking at, even if it is a form of material-based art – and this looking itself is influenced by the teachings of culture. Even then, it is the reflection that reaches us through light. I am not sure what my point is here, but what we perceive is a sort of a projection of physicality. In other words, when the process of studio work is almost complete, we begin formalising final decisions based on the understanding of how the viewer sees or experiences the artwork. Meaning that it is namely the projection of an artwork that we form – where the spotlight comes from or when the emerging shadow becomes much more important than the object itself. I can imagine that, for instance, with Sandra’s artistic work – importance is reflected in ways of engaging and handling the pieces, what words are exchanged, or has anyone bowed etc. Extremely tiny details may become a part of an artwork, a part of one’s artistic practice. Is there a postage stamp or a heart drawn on the package sent by Sandra – all this may influence the receiver. These are aspects not directly related to the physical artwork, but sometimes turn out to be even more important in forming an experience.

TH: There is the moral agenda, connected to the relationship between the global and the local. How have you defined this in your practice?

SK: Being a local means more opportunities to develop a better understanding of the problems and possible solutions related to a particular place. While leaving once in a while gives a perspective. I also agree with Juss, I find it important how we create. Through my practice I search for ways to cause the least harm possible to either myself or other people, other species or places.

DP: Localness and globality are actually not separate polarities. These phenomena are intertwined in a creative process. Both the local and global can be defined by geographical location; for instance, Estonia and the rest of the art world, but it is hard to take these separately, “the rest of the art world” always intervenes in Estonia through the screen.

TH: Juss, do you always carry clay in your bag when you travel?

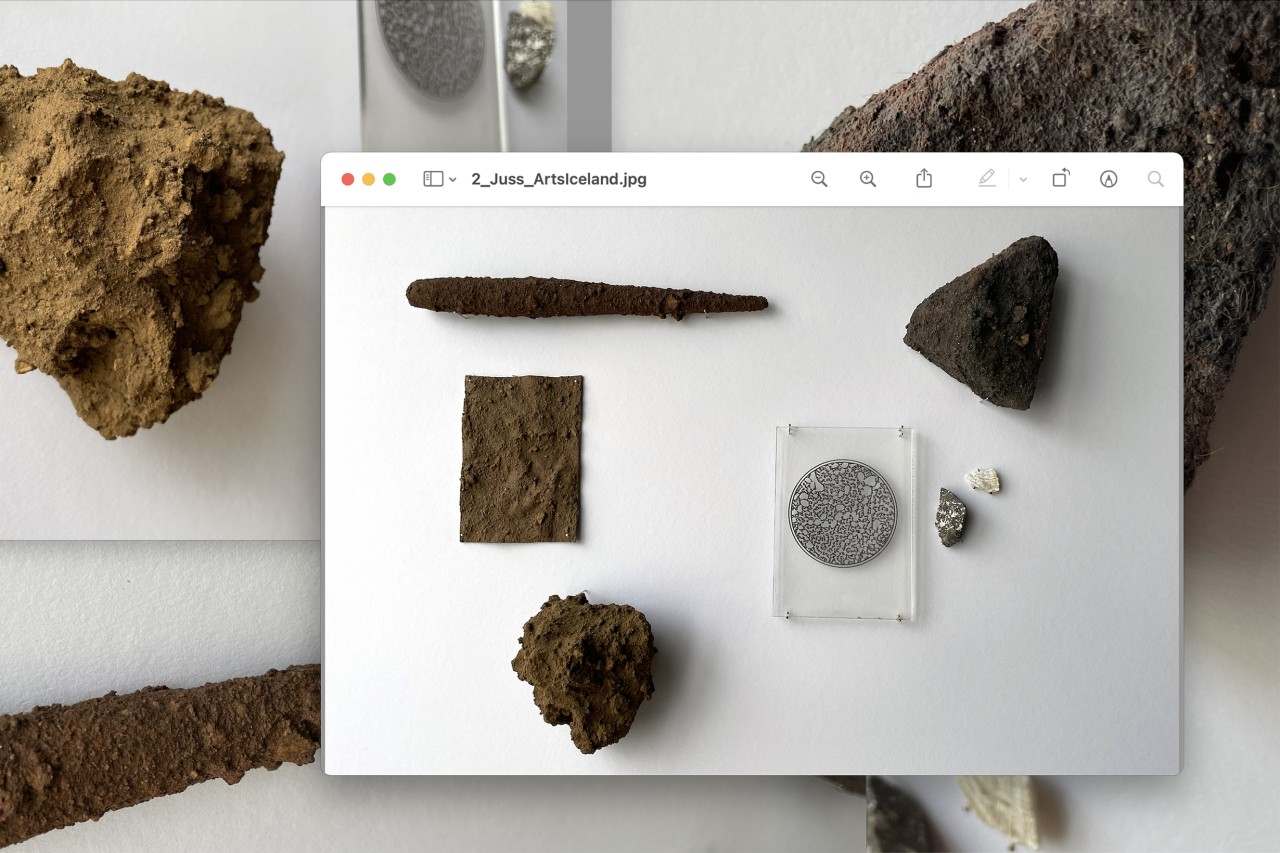

JH: (Laughing.) I always take something with me. I have hypotheses that I wish to prove and explore. These manifest themselves during the emergence of a specific collection of things or during a certain period of time. Whereas, the gathered sample of clay reflects the location it has been collected; one can recognize universal patterns and repetitions. It is true that I travel a lot and I could identify myself as a global artist. I feel connected with the place through material contact, no matter where I am.

The sense of belonging in the contemporary world is another issue. During the pandemic, the meaning of presence has been dissolved. We could establish a dialogue with anyone despite their physical location. We have become hybrid. Even today we talk via Zoom. We share the web space but not the physical one. Paradoxically, our so-called localness always remains. This is not influenced by the global collapse of distance. Moreover, wherever our minds may travel, we will never get rid of physicality. We perceive the world through our bodies. And what is interesting here is the development and importance of empathy and imagination.

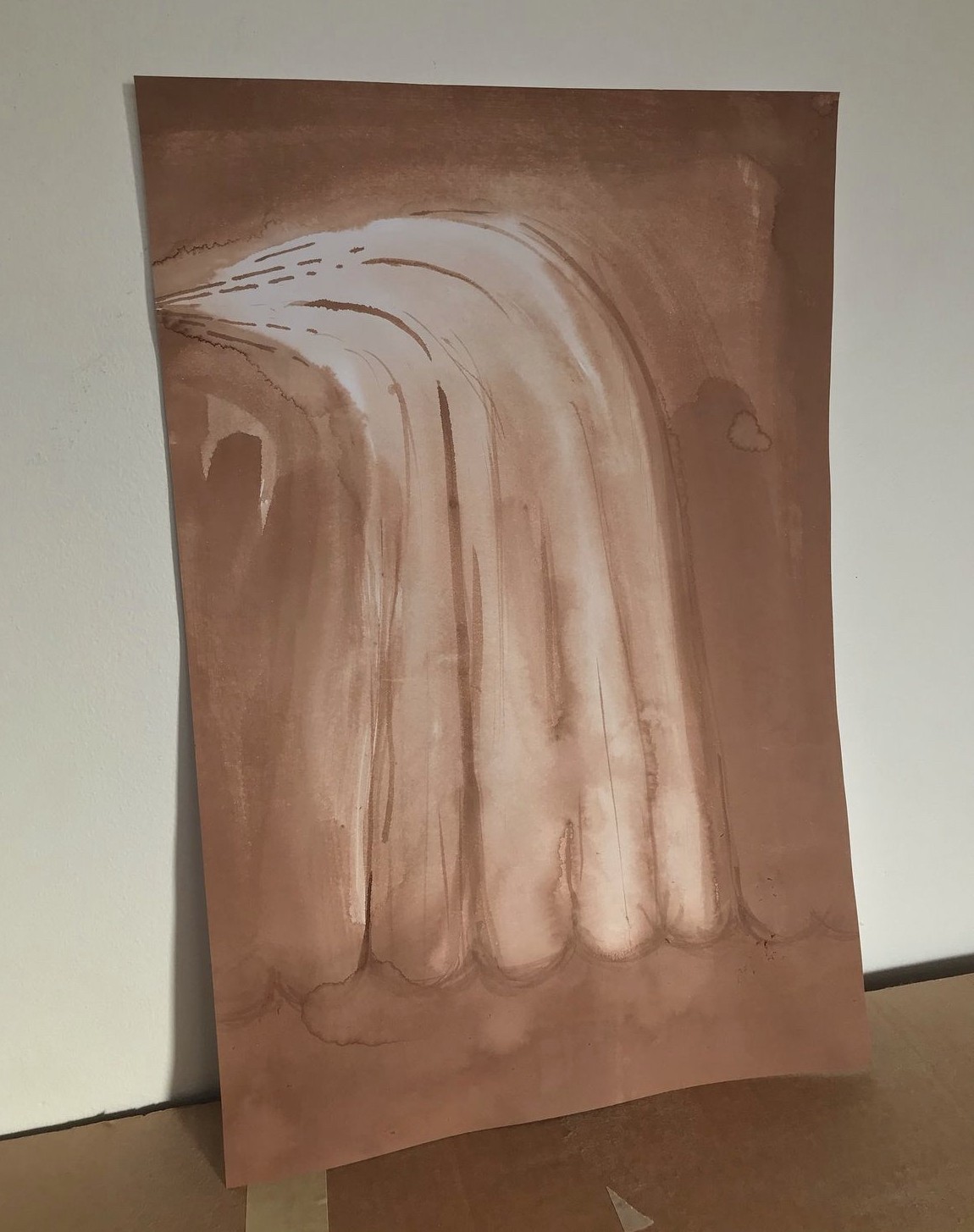

SK: I agree with Juss. Material is often something that connects me to a specific place. Recently, I have been trying to work without buying new materials, searching for local, surplus and seasonal materials instead. They often happen to be plants. For example, last winter while on a residency in Latvia, I made a beautiful tint from pine cones, which were abundant in the local forest. I also learned to process and fire naturally occurring clay that I found on the beach. And I built a loom from discarded cardboard boxes with the help of a YouTube video. I really like such empowering things. The fact that we can create our own tools. And creating tools can be a part of one’s artistic practice.

TH: I’d like to go back to the idea that Juss started to discuss – concerning the dialogue that is inevitably related to technological means or environments. When working with materials, is it possible to take the dialogue to a certain level where one will start to understand the material better? Can we talk here about some technologies that help to hold this dialogue with greater intensity, more meaningfully and leading to more results?

DP: Since I am interested in images in jewellery and how to influence the spectator’s perception, then it is inevitable that besides the physical objects I also work with the qualities of the screen, the fabric of video as a medium. Everything that I make into videos, for instance the close-ups of a small object, such as a piece of jewellery, could seem hyperrealistic through the 4K screen. Figurativeness should be absent there; we can only see the skin and the pores. Tactile materials that I have been using when making jewellery, for instance, brushes, have reached my artwork through ASMR. This is a recent internet phenomenon offering short videos with the aim of bringing pleasure to the viewer; for example, a video about a hedgehog eating insects and the sound has been recorded with a stereo microphone. And when talking about the features of a video image then glitches are also really important for me – you can see the image but you won’t understand or decipher it. Is it a whole object or what kind of a surface is it? As Laura Marks has said, it seems to touch the surface of the video with its eyes. Various editing techniques and special effects reflect the act of typing on a keyboard. When using these on purpose then I hope that the spectator will really experience something. These are the artistic techniques involved in my creative practice. For instance, Andres Lõo coined a word including both the meanings of perception and senses, a hybrid word, something like senseption (sense+perception)

TH: This reminds me of Marshall McLuhan’s phrase “the medium is the message” – but later when it had become an odd formula due to its abundant use, McLuhan together with a graphic designer wrote a small book titled “The Medium is the Massage”. This physical and slightly ironic aspect came forth quite well. As glitches or mechanical typing that help to keep one awake are quite interesting aspects.

SK: It is important for me to learn various technologies. Through my projects I have learned many different things like construction, sewing, making dyes. I am not afraid that I am not good enough at it – it’s not my purpose to create perfect things. I like to show that creativity is more important than the outcome. Recently, I have intentionally avoided using certain digital technologies in my artwork as these are excessively present in our daily use anyway. Through making art, I feel the necessity to create both a physical and mental space where the influence of digital technologies would not be that overwhelming.

DP: I understand that working with our hands is much more pleasurable than clicking a mouse. And at the same time I’d like to point out that the digital working process can also include bodily perception.

When you think of it, how often do you get angry when something fails in 3D? This is indeed a very physical experience. And when you finally succeed, then this in turn offers pleasure. The fact that everything is rendered and haptic-visual; for instance, the format of 3D cartoons has become much more tactile, you can see various scratches and everything has been brought very close – this will probably inspire future artists to create work with similar quality.

JH: And yet, artificial intelligence becoming superhuman won’t be the only consequence. If the digital world becomes central and true-to-life in artistic practice, then this will be counterbalanced by robustness and muddiness, genuineness and material tangibility. However, when we talk about material, there are always certain rudimentary elements included; for instance, there is this click when we take pictures with our phone, even if the shutter in the camera no longer physically moves. Why do we imitate something that is not existing anymore? Is it the effort to preserve the memory of tactility? Perhaps we are using technology namely for the purpose of recording the disappearing things? The fact that after completion, an artwork won’t be preserved but is only recorded or shared with the help of technology is ultimately a method of creative practice that we use more and more these days with increased awareness.

References

- In Estonian, the proposed word was ‘meelaline’ next to the word ‘meeleline’.