Published on 28.11.2025

Marite Kuus-Hill is an artist currently based in Tallinn, Estonia and Kjipuktuk/Halifax, Mi’kma’ki/Nova Scotia. Her practice involves curating, writing and cultural organising. Kuus-Hill is co-founder of the Halifax Art Book Fair and most recently curated the Nocturne public art festival in Kjipuktuk/Halifax. She is currently a student at the MA Craft Studies programme at the Estonian Academy of Arts, where she is focusing on social relationships to matter and material.

Between February and May 2025, I led a course titled Textile Theory for bachelor textile students at the Estonian Academy of Arts. The word textile comes from the Latin word texere, meaning ‘to weave’. This was the starting point for developing the course, in which we look at text as textile and textile as text. Textiles and texts borrow from each other a lot, and sometimes by using them interchangeably we can discover new avenues of thought. The following is an overview of one class during the course, wherein we tried a new way of looking for connections as an exercise in broadening our references.

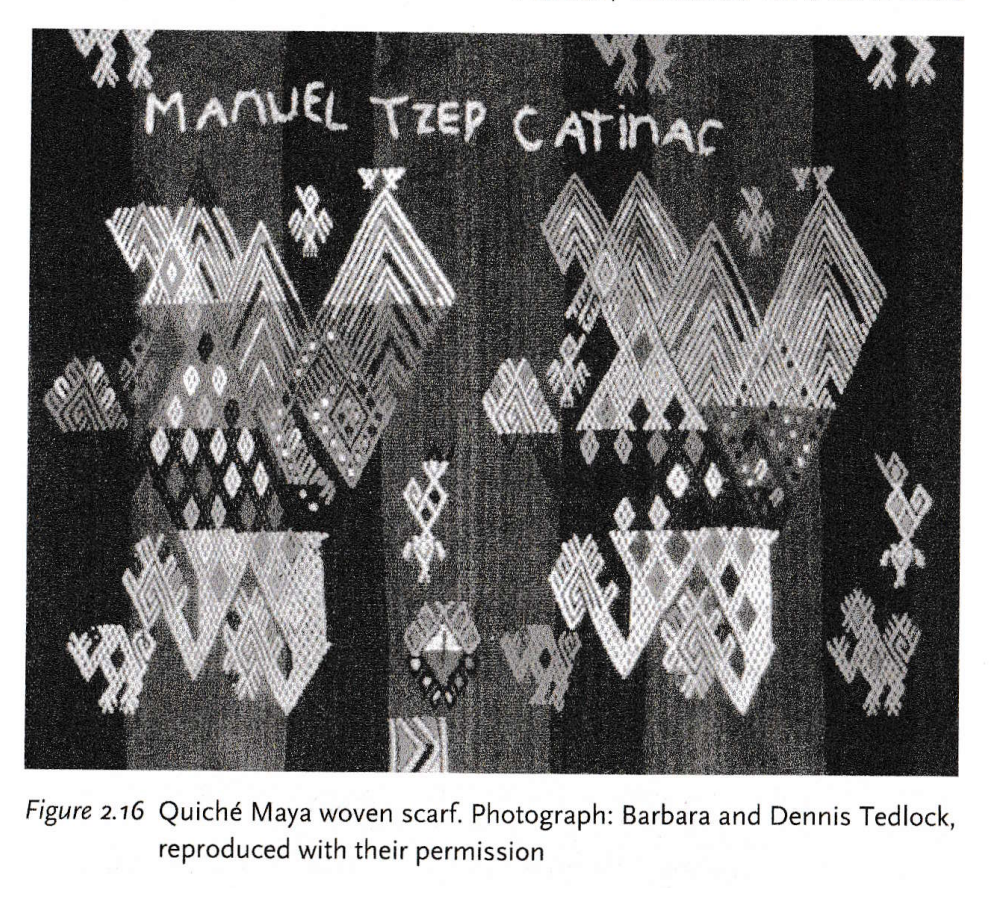

Text has for long been intertwined with textile. Before written text, textile was also used in documenting and markmaking. One example of this is the quipu, a record-keeping device used in the Incan Empire until the Spanish conquest in the 15th century. A quipu works by tying knots into fibrous cords, using colour, length and order to categorise information. It was used for many purposes such as tax and census records, as well as poems and genealogies.1

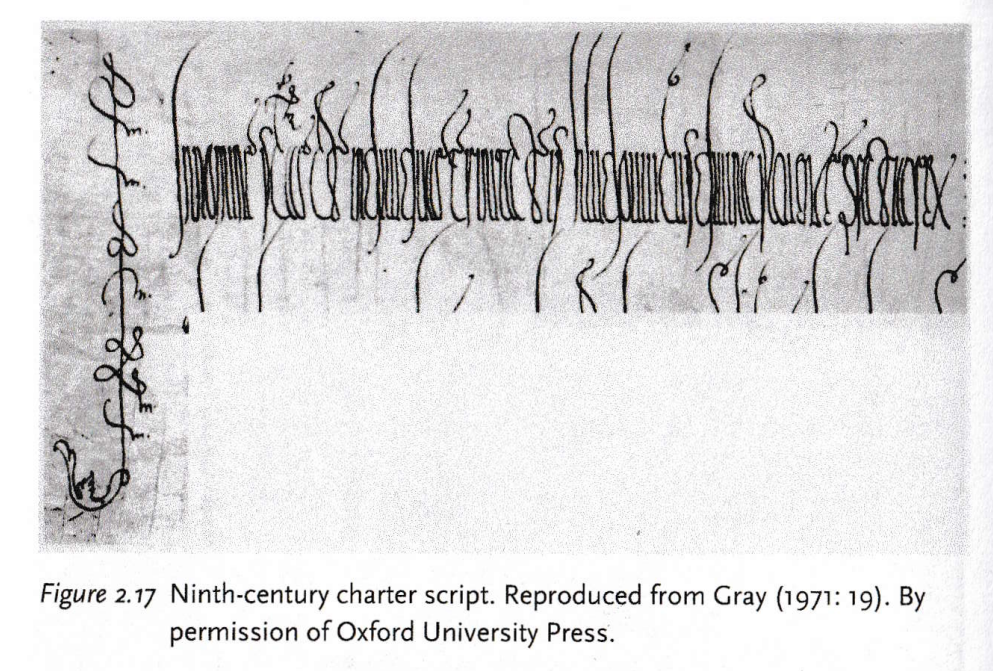

Similarities between textile and text are also prominent in written script. In the book Lines: A Brief History, Tim Ingold makes a visual comparison between writing and weaving, noting the similarity in the movement of creating both: ‘Just as the weaver’s shuttle moves back and forth as it lays down the weft, so the writer’s pen moves up and down, leaving a trail of ink behind it.’2 By comparing written text to woven lines, Ingold brings forth the physicality of written text, focusing on the movement it takes to create a line. By comparison, to view the woven line as a written word, the connection between text and textile becomes more evident.

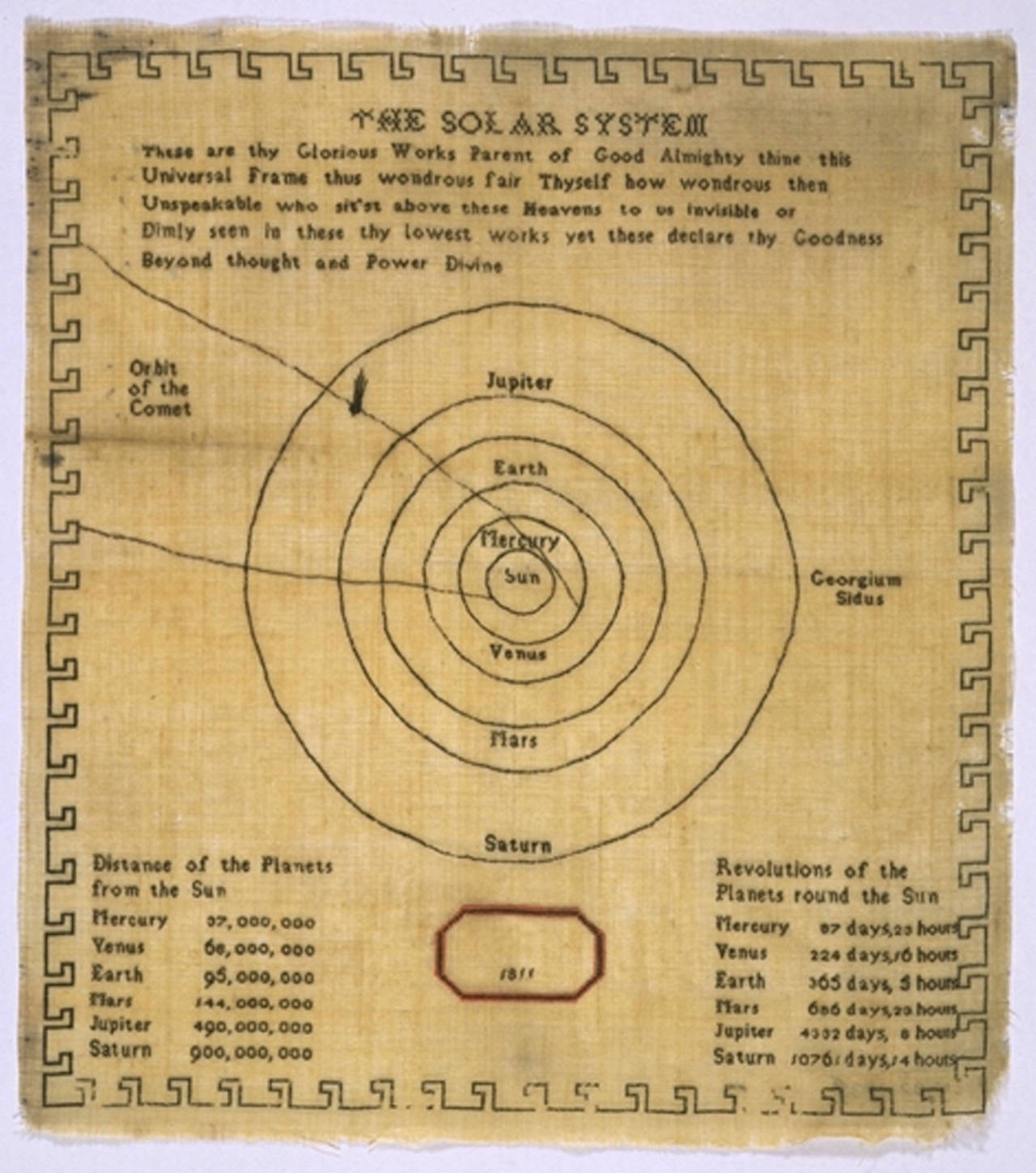

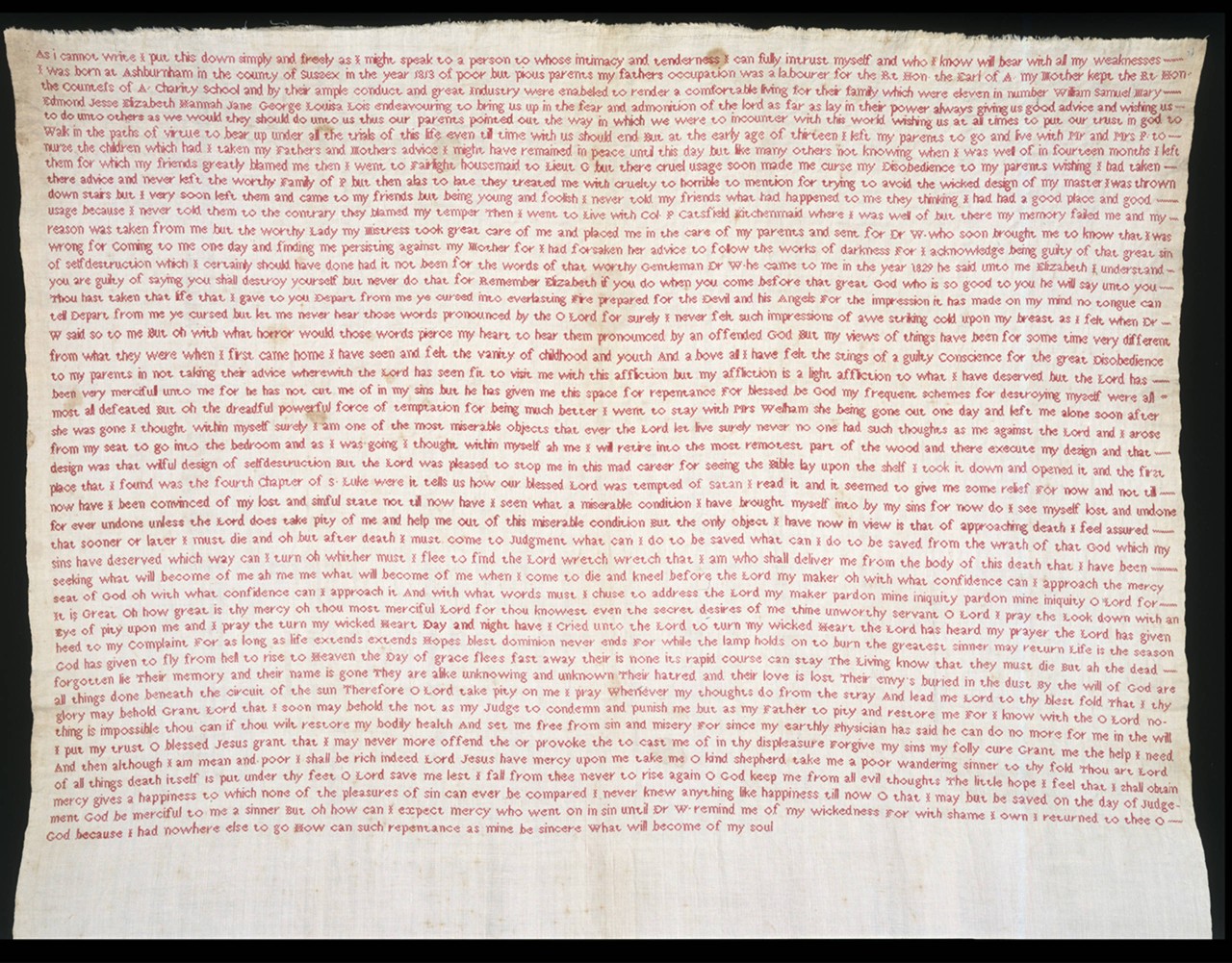

Maybe the most direct example of textile and text overlapping is embroidery. Embroidery was long used as an educational tool. Although the focus was on developing homemaking skills in girls, the medium of embroidery often served as a conduit to access other realms of information that was usually reserved for academic spaces from which girls were excluded. By looking at these examples from 19th century England, we can see that geography and astrology were deemed suitable subjects for practising embroidery, giving girls a glimpse into the sciences through the guise of embroidery. Alternatively, textiles can act as a space for meditation and personal reflection. An example of this is a confessional embroidery sample made by Elizabeth Parker when she was a teenager in 1830, documenting her work as a nursemaid and the mistreatment she suffered, detailing even a plan to take her own life, which she did not execute.3

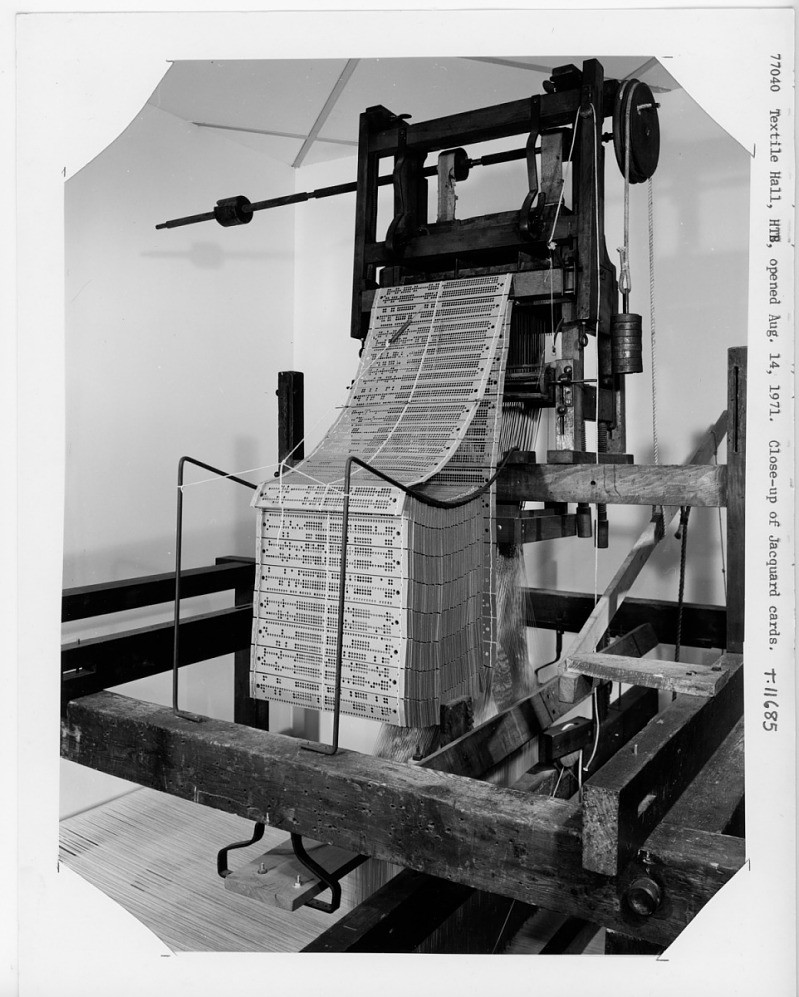

Taking text one step further, we can see textile as a frontrunner for all the digital communication we use today. The first computers were developed based on the punch cards used in Jacquard looms. The grid of alternating black and white, zeroes and ones, is the same baseline for both weaving and coding, allowing us to see textile even in the computational systems that we use every day. The simplification of text to binary code is a far cry from Ingold’s lines of calligraphy but the connection between textile and text is still applicable here.

During our last class of the semester, we visited the exhibition Between Borders, Between Materials at the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design. The exhibition ran from 2 May until 5 October 2025, curated by Ingrid Allik and Karin Paulus.

In preparation for the class, I asked the students to bring along a text of their own choosing, in contrast to the rest of the meetings we had wherein I had assigned them texts to read. While at the exhibition, I asked them to wander around and choose a work from the exhibition that relates to the text they had brought, which they would then introduce to the rest of the group. With this assignment, my aim was to simplify the connection between textile and text to the point where both were pared down to what was in the room with us. In this sense, the text can refer to the narratives it conveys as well as the conceptual imagery it invokes. We can look at text not just as words on a page but connect to the materiality it represents by pairing it with tangible material.

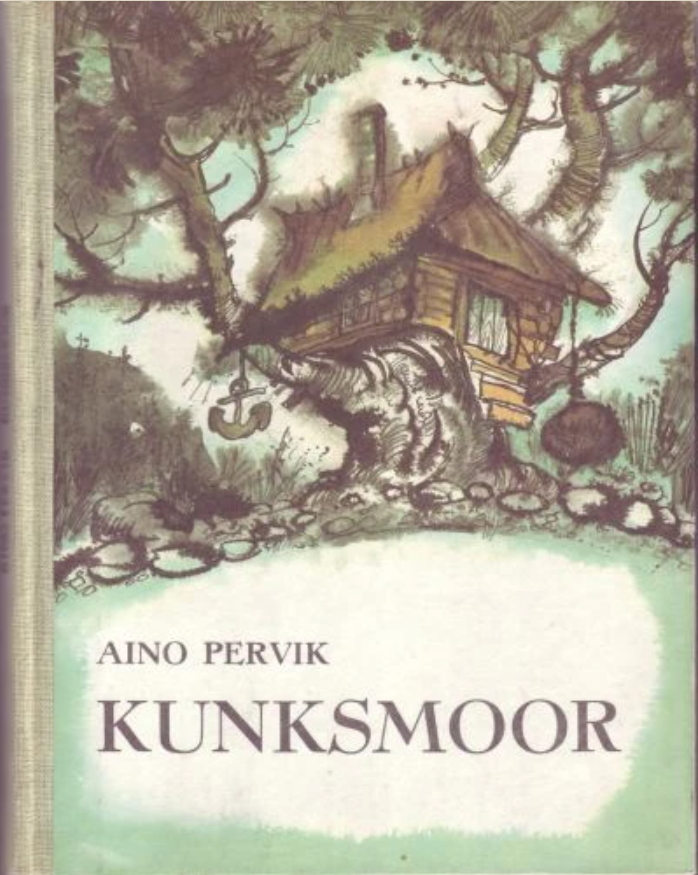

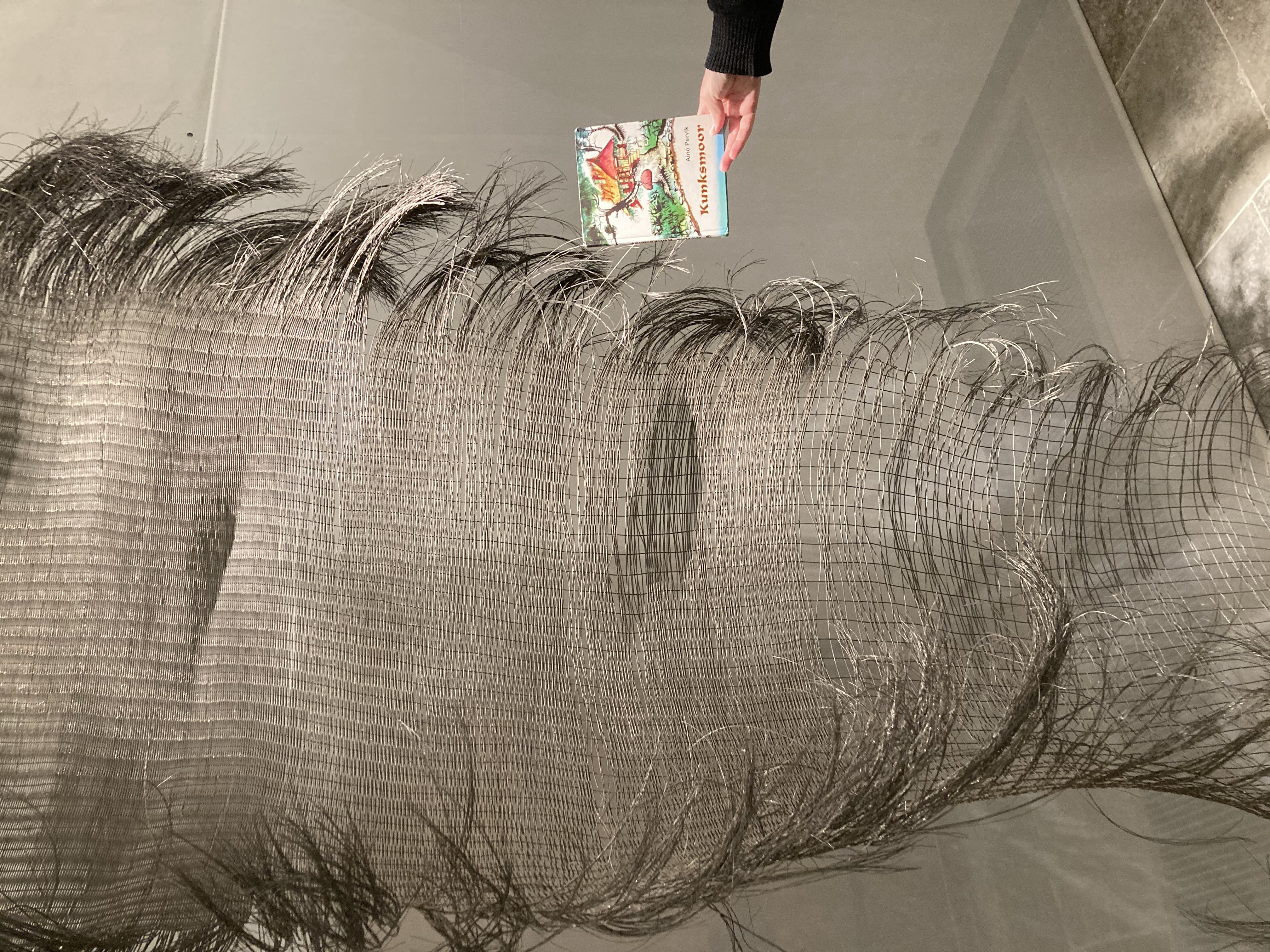

One of the students brought a 1973 edition of Kunksmoor by Aino Pervik, a popular Estonian children’s writer, which she paired with the work Soovid (Wishes), a weave made with stainless steel and copper by Katrin Pere. Kunksmoor is a children’s book character, a kind witch who lives in a treehouse on a remote island. The student observed that the metal weaving looks technically very difficult and frustrating to make, which she connected to Kunksmoor’s temperament and habit of seeking out tricky situations. Someone also mentioned that the rough wires at the selvedge of the weave resembled Kunksmoor’s wild, wiry hair. I found it interesting that this student had selected this book and the work to go with it because she had recently done a presentation in class about her family’s sheep farm and had told us about a traditional Estonian practice of bathing sheep in the sea. This combination revealed emerging themes in the student’s practice – of natural elements, of nostalgia, of a certain quaint grubbiness.

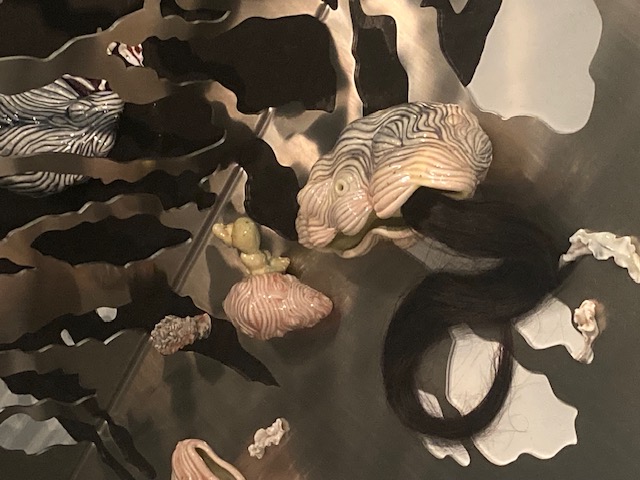

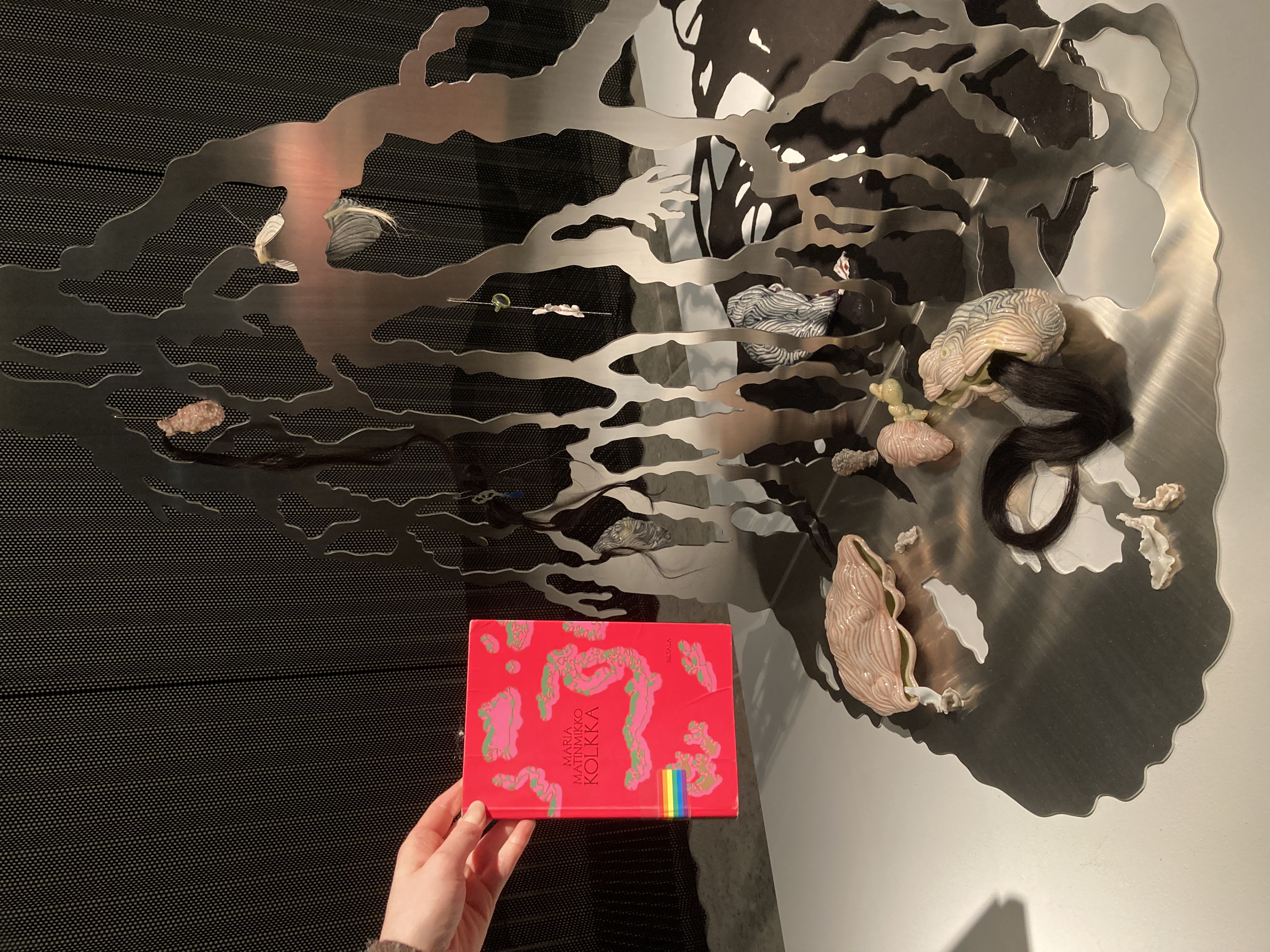

Another student brought a Finnish novel titled Kolkka (Backwoods) by Maria Matinmikko, published in 2019. She kindly offered to read aloud the love letter in the book which made her decide to pair the book with a sculpture by Eike Eplik titled They Take Root and Ring as If There Were A Tomorrow7. It’s worth noting that the student grew up in a bilingual Estonian-Finnish setting and had often voiced the feeling of being trapped between languages. She read the poem first in its original Finnish and then read her own translation in English. She mentioned that parts of the sculpture express parts of the poem which she feels unable to translate.

Tulen luoksesi minkä tahansa maaston läpi, mihin

Tahansa vuorokaudenaikaan.

Teltassa on savua, kippoja, simpukankuoria ja hiekka.

Sinun kasvosi valohämyssä: maailmankartta ja pääte-

pysäkki. Nahkatakki himmenee nuoruutta vasten,

kipu lävistää ihmisen levyinä. Mutta me olemme

nyt täällä teltassa, sinä ja minä. Sanon, mitä lähei-

sempi joku on, sitä tuntemattomampi ja monimut-

kaisempi. Juon kaivon tyhjäksi, kurkkuni sisäänpäin

kääntyneen janon. Astiat kaatuvat, meri kuoristuu.

Yritän tarttua reiteesi kuin mastoon. Tuuli tyhjen-

tää kasvot ja avaa ne muodottomiksi. Käpäläsi kuin

Jokin ehdoton hyvyys harjaa otsani rautaa, kalloni

vinoa valoa. Niin siinä kävi: sinun mielesi puhkesi

ruukkuuni, ruusu. Niin historiat kiertyvät, näyttävät

Simpukkamaiset reittinsä. Niin unesta havahdutaan

valveille, valveilta uneen. Ranta kohisee kuin pieni

rujo avaruus. Mutta me olemme nyt täällä teltassa,

sinä ja minä.

Ruususi aurassa kauhon ja läikyn, lämpimien

vesien kala.8

In this way, the material aspect fills in the gaps in language and text. Eplik’s sculpture features a sheet of stainless steel, bent to stand like a bookend, with cutouts of irregular blob-like shapes. Around the steel structure are various details of porcelain shell-like objects, jewellery and hair. The love letter in the book speaks of holes and shadows, which the student connected to the cutouts in the metal, as well as soft touches which brought to our attention the delicate touches of hair and softly glinting jewels. The longer we spent with the book and the sculpture in parallel, the more we saw, eventually even noticing similarities between Kaarina Tammisto’s cover design for the book, and the shapes on the metal. Was this a link that happened subconsciously, brought about by the action of bringing the two objects together in the same space?

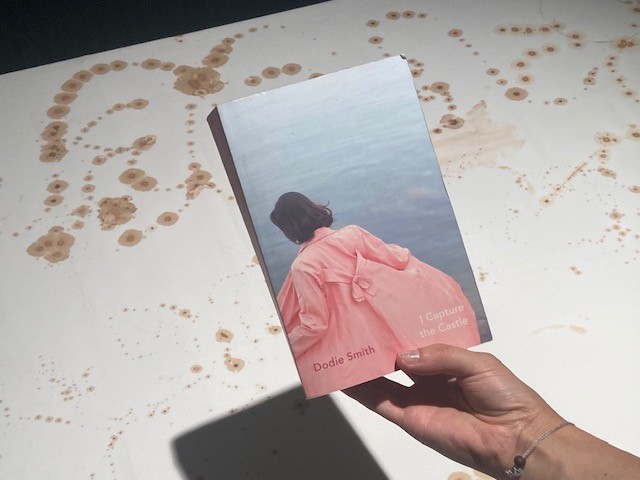

I visited the exhibition another time with a peer of mine, a student of the Craft Studies department at EKA who mainly works with ceramics. I was curious how someone from a different discipline would approach this exercise, considering that textiles and ceramics are both represented at the exhibition under the umbrella of craft techniques. This student brought along the book I Capture the Castle by Dodie Smith, first published in 1948, and decided to pair it with the work Tablecloth9 by Kärt Ojavee. The work is a stained tablecloth, serving as a material investigation and, in a way, a documentation. The tablecloth is covered in droplets and rings from the bottoms of glasses and cups. The student explained that in I Capture the Castle the characters are often sitting down together to drink tea because as a poor family this is one of the few ceremonies that they can afford, becoming a simple ritual. I couldn’t help but notice that in the connection between the fabric and the book, the ceramicist had instead brought into focus an object, the cup. I noticed that by pairing two different media we had arrived at a third; the combination of textile and text brought forth instead the ceramic cup.

This exercise allowed us to connect different materialities in a physical space and see elements in both the exhibited works as well as the texts that we brought that we otherwise potentially would not have noticed. Craig Leonard, a former professor at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design in Canada has an exercise called Performing the Library, which he conducts with students in his Printed Matter class. The exercise focuses on finding texts by browsing the bibliography of a book or by looking at books that are adjacent on the shelf, rather than through databases or other search tools. By using the book as an object and seeing the action of browsing at the library as a choreography and performing it, it brings forth another dimension of the space, one that focuses on the physicality of books and browsing, rather than the conceptual dimension of the text in a publication. This can also remove a lot of pressure and ceremony from a potentially daunting academic space, by interacting with it through play or pantomime. This is also what I aimed to do with the textile students at the exhibition. By using a book as a grounding tool to select a work it allows you to pay attention to a work through a different set of characteristics, ones that don’t immediately engage the conceptual meaning of the works. The exercise allows you to focus on the materiality of the physical space around you, leaving space for the conceptual significance to be revealed later.

Performing the library I

- Retrieve the call number of a book by an author of interest related to your research.

- Find the book in the library and carry with you.

- a) From the book’s bibliography, select a book of interest and find it in the library; or b) If no bibliography, peruse adjacent shelved books until you find a book of interest with a bibliography.

- Repeat #3a/b until you have collected five books.

- Sit and skim attentively through the books you have collected.

- Keep the books if relevant to your research; put aside those that aren’t.

Performing the library II

- Retrieve the call number of a book on a theme of interest related to your research.

- Find the book in the library and carry with you.

- a. From the book’s bibliography, select a book of interest and find it in the library; or b) If no bibliography, peruse adjacent shelved books until you find a book of interest with a bibliography.

- Repeat #3a/b until you have collected five books.

- Sit and skim attentively through the books you have collected.

- Keep the books if relevant to your research; put aside those that aren’t.

The title of the exhibition, Between Borders, Between Materials, also reflects the blurring of boundaries between materials and techniques, as we see from the contradiction of rough textile by Katrin Pere and tender metal by Eike Eplik. The curators Karin Paulus and Ingrid Allik bring forth the idea of ‘merging meanings’, asking whether ‘there are persistent “obsessions” linked to materials that drive the artist to weave or sculpt in a specific way?’10 The curators also mention the role of ‘fellow travellers’, musing on who a collaborator could be, for example, a partner, co-author or technician. I would suggest that a ‘what’ could also be a collaborator, especially if the exhibition seeks to go beyond borders and materials. ‘Increasingly, artistic authorship resembles a collective – as has long been the case in architecture and design’, thus the curators ask: ‘Does this suggest that art has become synergetic?’11

I would argue that art needs to be synergetic to find new angles. Art needs to cross boundaries and cross-pollinate to find meaning and perspective. The principles of looking at textile as text and vice versa allowed our Textile Theory class to see textile in places where they hadn’t seen it before and bring text into their work through unassuming ways. By attaching arbitrary books to works at an exhibition, we saw new layers in the story and created a narrative to the work which before felt impenetrable. Crossing boundaries between material and medium is not just a step within a process, but an outcome in itself. The outcome isn’t material or concrete, it’s rather a step towards something else. We have arrived not at an answer but a possibility for further inquiry. Things go unseen with tunnel vision, a crossover is sometimes needed to shed light on new connections, and this was an exercise for a different way of questioning.

References

- Museo Chileno de Arte Precolombino, Quipu: Counting with knots in the Inka Empire <https://precolombino.cl/wp/en/exposiciones/exposiciones-temporales/exposicion-quipu-contar-anudando-en-el-imperio-inka-2003/quipus-y-cuentas/los-quipus-de-laguna-de-los-condores-region-de-chachapoyas-peru/#!prettyPhoto> [accessed 15 September 2025].

- Tim Ingold, Lines: A Brief History (Routledge, 2007), p. 72.

- Embroidery – a history of needlework samplers, Victoria and Albert Museum <www.vam.ac.uk/articles/embroidery-a-history-of-needlework-samplers> [accessed 15 September 2025].

- Ibid.

- <www.ibm.com/history/punched-card> [accessed 15 September 2025].

- <www.si.edu/object/jacquard-loom:nmah_645517> [accessed 15 September 2025]

- Eike Eplik, Nad ajavad juuri ja helisevad, justkui homme oleks (olemas), 2024.

- English translation by textile design student Pihla Alina Teder:

I will come to you, through every landscape, whatever

time of the day.

In the tent there is smoke, jars, seashells and sand.

Your face in the light shadows; map of the world and vanishing

point. A leather jacket fades against youth,

pain pierces through a person as sheets. But we are

here now, in the tent, you and me. I say: the closer

someone is to you, the unknown and complex

they are. I drink the well empty, introverted thirst

in my mouth. Dishes fall over, sea hatches.

I try to grab your thigh like the terrain. The wind

empties the face and opens them without form.

Your paw like some unconditional goodness pets

my forehand’s iron, crooked light of my skull.

And so it happened, your mind blossomed

in my jar; a rose. So the history twirls, shows

it’s clam like routes: so you wake up

from a dream, fall asleep again. The shore

rumbles like a small crippled universe. But we are

here now, in the tent, you and me.

In the aura of your rose, I splash and scoop,

the fish of warm waters.

Maria Matinmikko, Kolkka, 2019, Siltala, Helsinki, pp. 137–138. - Kärt Ojavee, Laudlina, 2007.

- Ingrid Allik, Karin Paulus, exhibition text, Between Borders, Between Materials, Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design, 2.5–5.10.2025.

- Ibid.