Published on 14.06.2024

Jaana Päeva is a bag designer, a researcher at the Faculty of Design and head of the Art and Design PhD programme. She is interested in sustainable values and the process of meaning-making which she studies using the methods of practice-based research, combining historical artefacts and traditional techniques with theories of product semiotics, emotional design and product attachment. Her research and creative practices focus on bag design, simultaneously facing the past as well as the future, remaining material-centric and valuing quality and craftsmanship.

From the point of view of design, history is an important discipline since every moment in time and everything that is created in that moment is located on an axis between the past and the future: it has a context and it is dependent on the interpretation of history. Ton Otto believes that the process of designing presupposes a simultaneous vision of the past and the future since designing and planning changes also contains the conceptualisation of the past. To “open up” the future to new opportunities, the past also has to be “opened” in order to find possibilities and as yet unmapped viewpoints for carrying out the desired changes.1 A desirable future relies on both our current needs as well as on the preconditions created in the past. Michael North goes even further with his definition of novelty and innovation, finding that newness cannot be created without referring to the past. Everything new is fresh and innovative only in comparison with the past which didn’t contain it. He finds that the 21st century “produces revolution from routine” or that the most common model for creating something fundamentally novel is based on incremental repetition.2

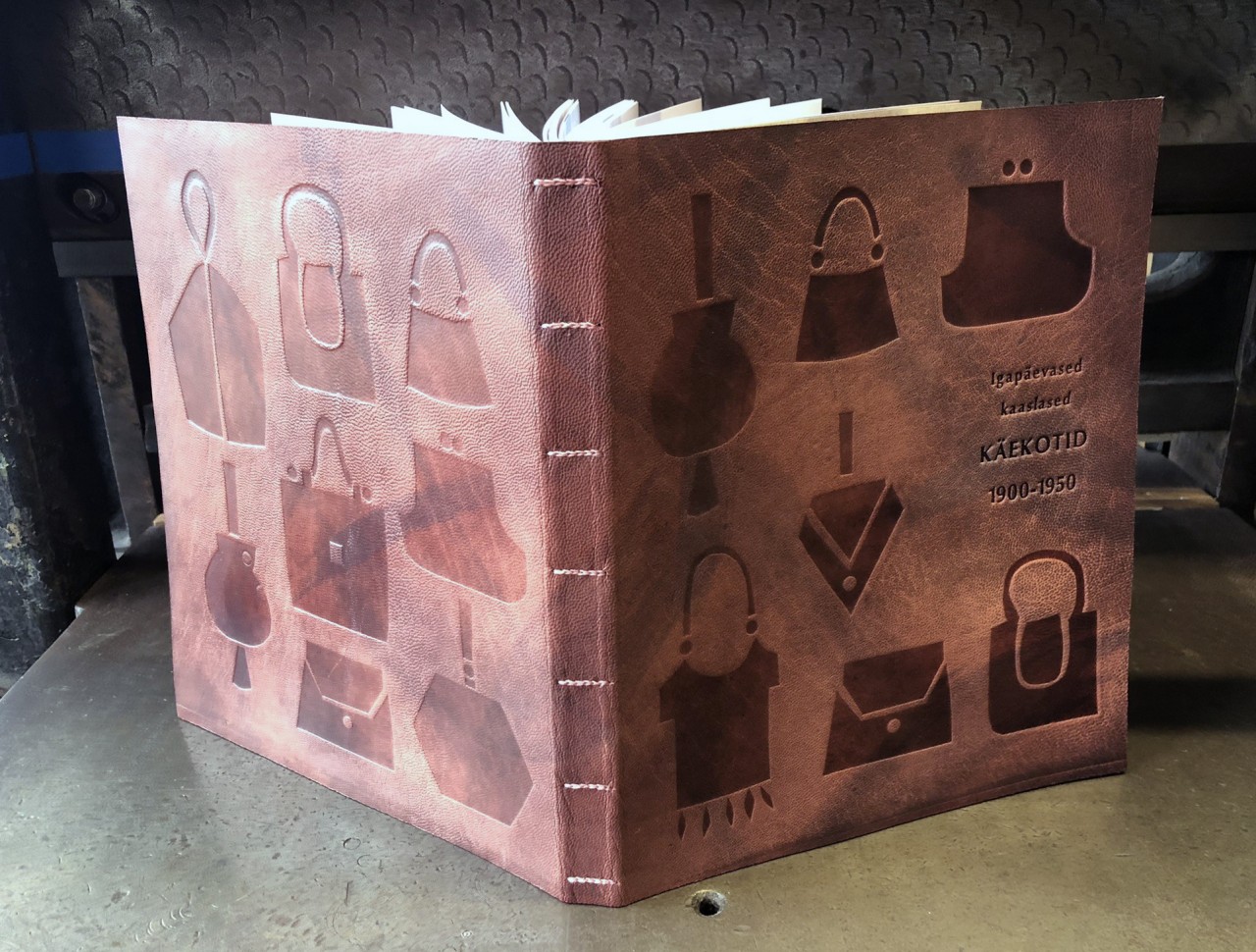

Based on the aforementioned idea and understanding that a thorough reflection of the past plays an important and potentially innovative role in designing the future3, this article introduces the opportunities which the research of traditional techniques with contemporary means can offer us in the face of our changed needs. It is based on the creative study Reconstruction and Creative Development of Historical Relief Printing carried out at the Estonian Academy of Arts which “reinvented” and developed a leather decoration technique that had been used in 1924 at the studio and workshop of the Estonian leather artist and bookbinder Eduard Taska and had later been forgotten.

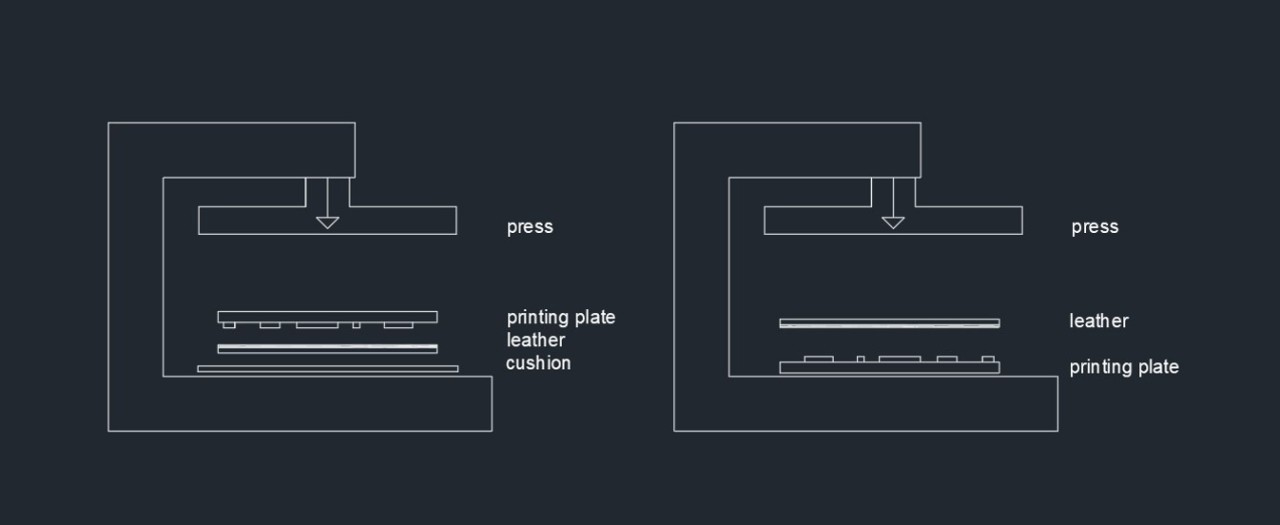

Of the technique under research, two patterned leather handbags survive in the collection of the Estonian History Museum (AM 15737/1 and AM 15737/2). The technique is a relief print or a method of decoration where a relief gets added to the surface of the leather by pressing it with a printing block. It is distinct from the usual metal cliché or linoprint by its two-dimensional result and the absence of graphic lines. As a distinct feature, the pattern is pressed onto the material without reinforcement glued to a base. As a team, we examined the technique used on the handbags in detail, comparing it to our own experiences and established a number of hypotheses of how it might have been achieved. Through subsequent experiments we tried to achieve a result that would be as close to the one seen on the handbags as possible using techniques, tools and materials as historically accurate as possible. We varied the materials that are suitable for the printing plate, tested both cold and hot pressing and determined the optimal set-up of the press. By comparing both sides of the experimental samples and increasingly improving our hypothesis, we arrived at a technique that is visually similar to the historic one, but which we called reverse printing. In conventional circumstances, a printing press pushes the printing plate against the right side of the material resting on the press base. To achieve a result similar to historical printing, a method was invented where the printing plate is placed on the press base with the pattern facing upward, leather is laid on top towards the printing plate, and the press, in contrast to the usual situation, presses the leather against the printing plate. (Figure 1)

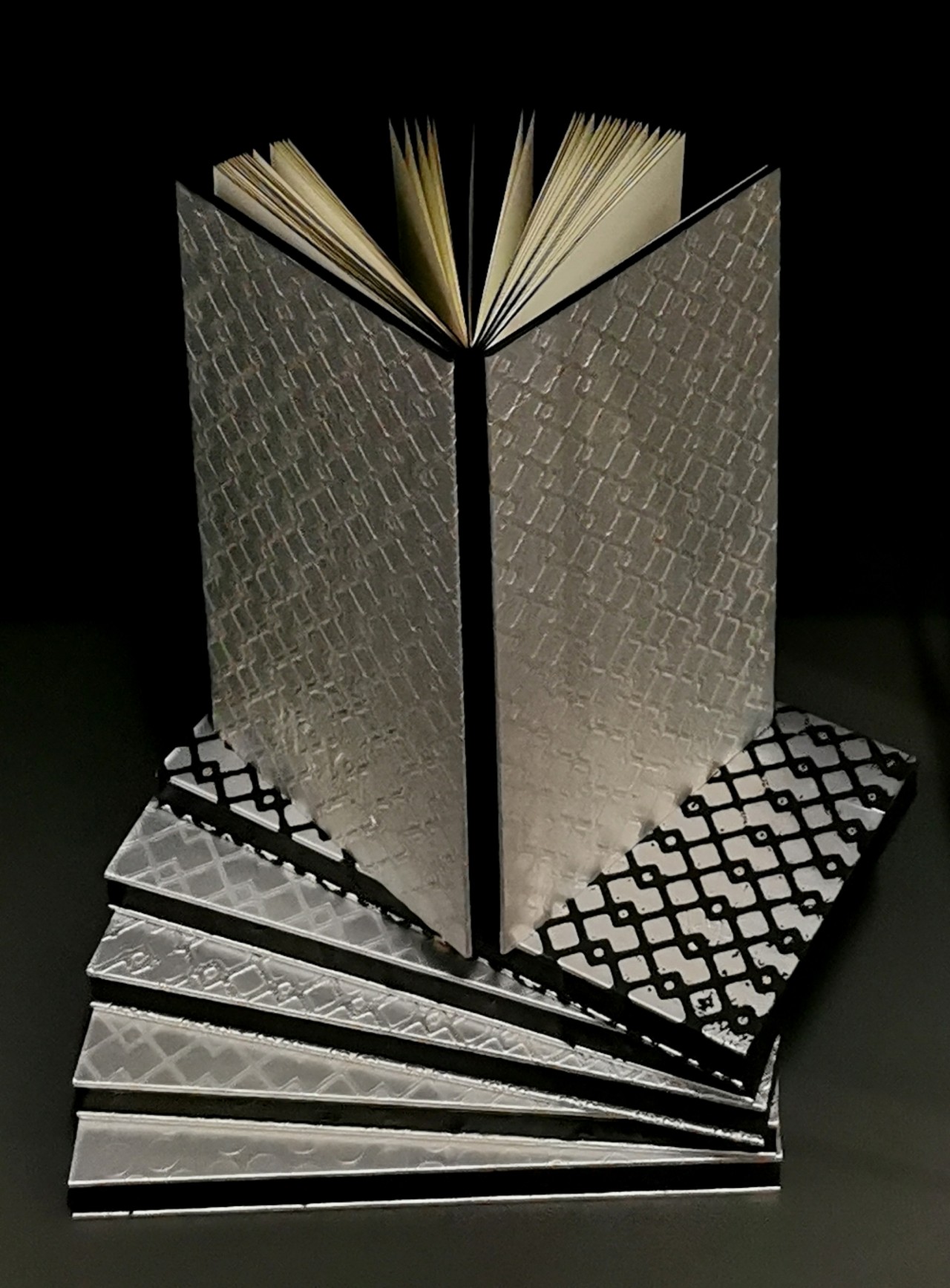

Due to the uniqueness and future potential of the technique, we continued its development and innovation in three directions. First, we experimented with cheaper and more easily available materials for the printing plates and with different manufacturing methods. For example, we CNC-ed a plate out of MDF board and laser engraved a linoleum plate. We also used laser cutting to add patterns onto waterproof electric insulation boards as well as onto various plastic plates. Second, we researched the effect that different pattern types had on the success of the reverse printing, meaning that we tested the ratios between patterns and their backgrounds, resulting in versions where the pattern remained higher and brighter or controversially lower and darker than the background. Up to this point we made all the printing tests on vegetable-tanned leather so that the results of different printing plates could be compared. However, as a third area of research, we started testing reverse printing on leathers with different tanning and surface treatment methods, textiles, washable paper, cork fabric and finally on recycled materials such as bonded leather, non-woven fabric leftovers and waterproof packaging for coffee and dog food.

In conclusion, we can say that the project was a success. The results of the tests showed the potential for developing reverse printing because a number of reusable and recycled materials could be used as printing plates, which means that the price, time spent and environmental impact of cutting the pattern is considerably lower than in conventional printing methods. The printing plates can be made using different technologies from manual to digital depending on the needs and the skills of the maker. Reverse printing is also an affordable option for relief printing large-scale patterns compared to the cost of etching the cliché or cutting the linoleum. Reverse printing can be used on materials that have defective surfaces: the relief and the differences in tonality enhance leather that has a modest facture or none at all while at the same time concealing surface mistakes and imperfections. Patterning can also be used to enhance and customise reusable materials like coffee packages or similar. The wide selection of printing plates and printable materials, as well as the extensive selection of technologies for making the plates offers potential for developing the technique and adapting it according to available technologies and needs. (Images 1–2)

Arjun Appadurai claims that objects are surrounded by two types of knowledge. First, input type knowledge which covers the technical, social and aesthetic know-how necessary for making them, and second, output type knowledge or know-how related to consuming the items. These two types of knowledge will diverge from each other proportionally as the social, spatial and temporal distance between producers and consumers increases.4 In collaboration with the reinvention and creative development of reverse printing, it became clear that researching known traditional techniques with new methods or from new viewpoints could offer similar novel knowledge. This will definitely increase the technical capabilities of the subject, but will also expand the user base of any given technique.

Empirically, the descriptions of traditional techniques are too superficial for self-training, and lack the nuances needed for success. Skills are usually obtained through practice and training, the skill is dispensed from masters to students through observation and imitation. The context of practice-based research will change this situation because it forces the participants to document their actions, the sequence of movements and the placement of materials and tools, and to notice, verbalise and interpret their mutual relations. During the process of experimentation, we made the descriptions of our experiments and actions increasingly explicit, increasing the detail and nuances, which, in turn, allowed us to start analysing the necessity of our actions, to justify our choices and to reach logical conclusions. For example, we formulated one of the most significant differences between regular and reverse printing. In regular hot stamping, the heat emanating from the press first passes through the plate and only then reaches the printed material, but in reverse printing the heat first passes through the material, only then reaching the printing plate. This led us to conclude that the material of the printing plate used for reverse printing does not have to be made from highly heat conductive material, which allows us to use a wide variety of options like leaves, feathers or lace doilies. This observation led us to experiment with foil printing. Foil is an extremely thin sheet material which is placed between the printed material and the printing plate during hot printing and the layer of colour on it will be transferred to the printed material at certain temperatures during the process. In regular relief printing, the printing plate has to be a good conductor of heat (e.g. metal) to impact the foil, but in reverse printing the heat was transferred to the plate and impacted the foil on top of it through the printed material. The experiments thus far show that reverse printing allows us to use foil for printing relief images using any pressure and heat resistant material as well as ready-made objects and the patterns created out of them as printing plates. (Images 3–4)

The precision of modern machinery allows us to monitor the technical processes which, in turn, enables us to make the solutions found through trial and error repeatable. The mastery of many traditional leather designing techniques is based on experience. For example, the combination of the pressure, duration and temperature needed for relief printing, is identified on any given machine through experimenting. (Images 5–6) The more experience you have, the faster the desired result can be achieved. In the reconstruction stage of the project we monitored the entire tuning of the machine from the very first tests, which meant that by the time we arrived at reverse printing, we could also identify the optimal settings for its success: press heated to 120 °C must use 1500 N of compressive force to press the leather for 30 seconds. This was a good starting point for the subsequent experiments and it accelerated the whole process significantly. This taught us that systematically mapping the appropriate conditions of a technique using new technologies will accelerate the speed of applying the technique and simplifies its use which means that the potential user base of the technique will also grow.

During the creative research, we used many novel technologies: CNC milling, laser engraving and laser cutting. These allowed us to create very precise and detailed printing plates, but also require digital skills during preparation and specialised machinery during production. Taking into account that reverse printing is suitable for prototyping and for creating products with unique or limited print runs, we focused in our research on the choice of materials which would simplify the process of making printing plates for new users. For example, we used packaging cartons, plastic laser cutting leftovers and items with suitable patterns and textures for creating new patterns. (Images 7–8)

We discovered that details cut from 1mm thick magnetic sheets using scissors or a knife can be easily combined with a steel plate because the elements of the pattern magnetically attach to the steel base and moving them around on the plate to achieve different compositions is simple. The amount of detail, their direction and mutual distances can be varied. With limited resources it is possible to exchange or add new details and to reuse old ones. (Images 9–10)

In conclusion, it can be said that the research of historic techniques allows us to continue our connection with the past, protecting, preserving and understanding what is traditional and characteristic to our culture. At the same time, this also allows us to learn from these techniques and to obtain new knowledge, to adapt this to the spirit and the needs of the era. When Susan Stewart talks about design education, she calls such uninterrupted progression “care”, defining care as understanding that the past and the future are connected. Where we are headed to, what we notice and what we care about, but also what and how we create in any given moment, is dependent on the historic epoch in which we live.5 Interpreting the past influences the future where we are headed. Following the ideas of Anne-Marie Willis: we design the world while the world designs us.6

Project team: EKA researcher Jaana Päeva, EKA Bookbinding Workshop Manager Eve Kaaret, technologist from the IKIGI book binding garage Lennart Mänd and EKA textile design MA student Riina Samelselg

Project partners: IKIGI OÜ and Estonian History Museum

Project funding: Ministry of Culture’s Artistic Research Support Programme in the field of culture and creative industries

References

- Ton Otto, ‘History In and For Design’, Journal of Design History, 29(1) (2016), pp. 58–70.

- Michael North, Novelty. A History of the New (Chicago, London: The University of Chicago Press, 2015).

- See, for example: Ton Otto, ‘History In and For Design’, Journal of Design History, 29(1) (2016), pp. 58–70; Sarah Ganz Blythe, ‘Object Lessons’, in The Art of Critical Making. Rhode Island School of Design on Creative Practice, ed. by R. Somerson, M. L. Hermano (Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons, 2013), pp. 116–137.

- Arjun Appadurai, ‘Introduction: commodities and the politics of value’, in The Social Life of Things: Commodities in Cultural Perspective, ed. by A. Appadurai (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1986), pp. 3–63.

- Susan Stewart, ‘And so to another setting…’, in Design and the Question of History, ed. by T. Fry, C. Dilnot, S. C. Stewart (London: Bloomsbury, 2015), pp. 273–301.

- Anne-Marie Willis, ‘Ontological designing’, Design Philosophy Papers, Volume 4, Issue 2 (2006), pp. 69–92.