Published 14.06.2024

Liza Sedler is a doctoral student in the Institute of Art History and Visual Culture at the Estonian Academy of Arts, as well as a collection keeper of the cultural and historical collection of Tallinn City Museum. She has studied interior design at the Estonian Academy of Arts and Aalto University in Helsinki and worked for various architecture companies. In her research, she focuses on the design history of everyday objects and their representation in popular media.

When talking about kitchen design, one is most likely thinking about built-in kitchen furniture, its configuration and finishing. The ‘morally outdated’ kitchen furniture and appliances are eagerly traded for new ones, with money and time spent, turning a blind eye to the amount of construction waste and the huge CO2 footprint produced. The excuse for this guilty pleasure is a sincere belief in the enhanced functionality of the new kitchen design. The default version of the modern kitchen already contains everything necessary for effective cooking, which lets the consumer focus primarily on questions of style, deciding between classical, Scandinavian, minimalist etc.1 The ‘timeless look’ of the kitchen is gained using materials like wood, natural stone, steel, glass and even concrete that are ‘one hundred percent natural, with unique colours and design’.2,3 Despite the need for regular cleaning, polishing and oiling, this type of kitchen still encompasses the idea of its original functionality for the average consumer.

The social mechanism behind this phenomenon may be explained by the economist Thorstein Veblen’s (1857–1929) term ‘conspicuous consumption’. In The Theory of the Leisure Class (1899), Veblen assumes that the consumer is never free in their choices. The acquisition of goods is always accompanied by a cultural value, for which the consumer is willing to expend their resources. Consumption does not occur only to satisfy basic needs, instead it is an act of confirming one’s social status. A similar theory was developed by the sociologist Georg Simmel (1858–1918) regarding fashion (Fashion, 1904). He elaborated on the theory of consumption by stating that the best way to confirm one’s social status is to consume fashion and trends. Fashion creates role models and thus the possibility to resemble the majority. At the same time, it also creates opportunities to stand out for those who have enough money to buy fashion items. Simmel’s theory is also applicable to the phenomenon of ‘kitchen fashion’. An up-to-date kitchen design and its representations implicitly reproduce the current cultural norms, satisfying one’s need for social recognition.

The radical transformation of the cooking room that had been considered secondary so far, was encouraged in the beginning of the 20th century by household experts and architects who aspired to alleviate the laborious work done in the kitchen. Both design history handbooks and design museums underline the heroic innovations related to the modernised kitchen design. At the same time, not enough attention is paid to the commercial aspect that followed the evolution of the kitchen. Manipulations of the image of the domestic kitchen in advertising, media, and architectural history guides show how the home kitchen gained the reputation of an efficient and rational space, while simultaneously losing its connection to cooking.

The reformers of the domestic kitchen were inspired by the American Christine Frederick’s (1883–1970) book The New Housekeeping (1913). Looking for solutions to reduce the workload of the middle-class housewife, she suggested applying industrial engineer Frederick Taylor’s scientific management principles, which were aimed to increase work productivity by making the working hours more efficient.4 Following the example of the factory assembly line, she put the different activities related to cooking, like preparing, heating and serving food, as well as cleaning up after a meal in order, and then organised the kitchen cabinets and appliances according to these operations. Written in the first person, The New Housekeeping might give a false impression that Frederick herself had been a worker in her own domestic kitchen-factory. But Frederick’s biographer, Janice Williams Rutherford, has pointed out that at the height of her career, the ‘household efficiency engineer and kitchen architect’ started devoting more time to marketing her ideas for home kitchen remodelling, thus delegating her domestic duties to paid housekeepers.5

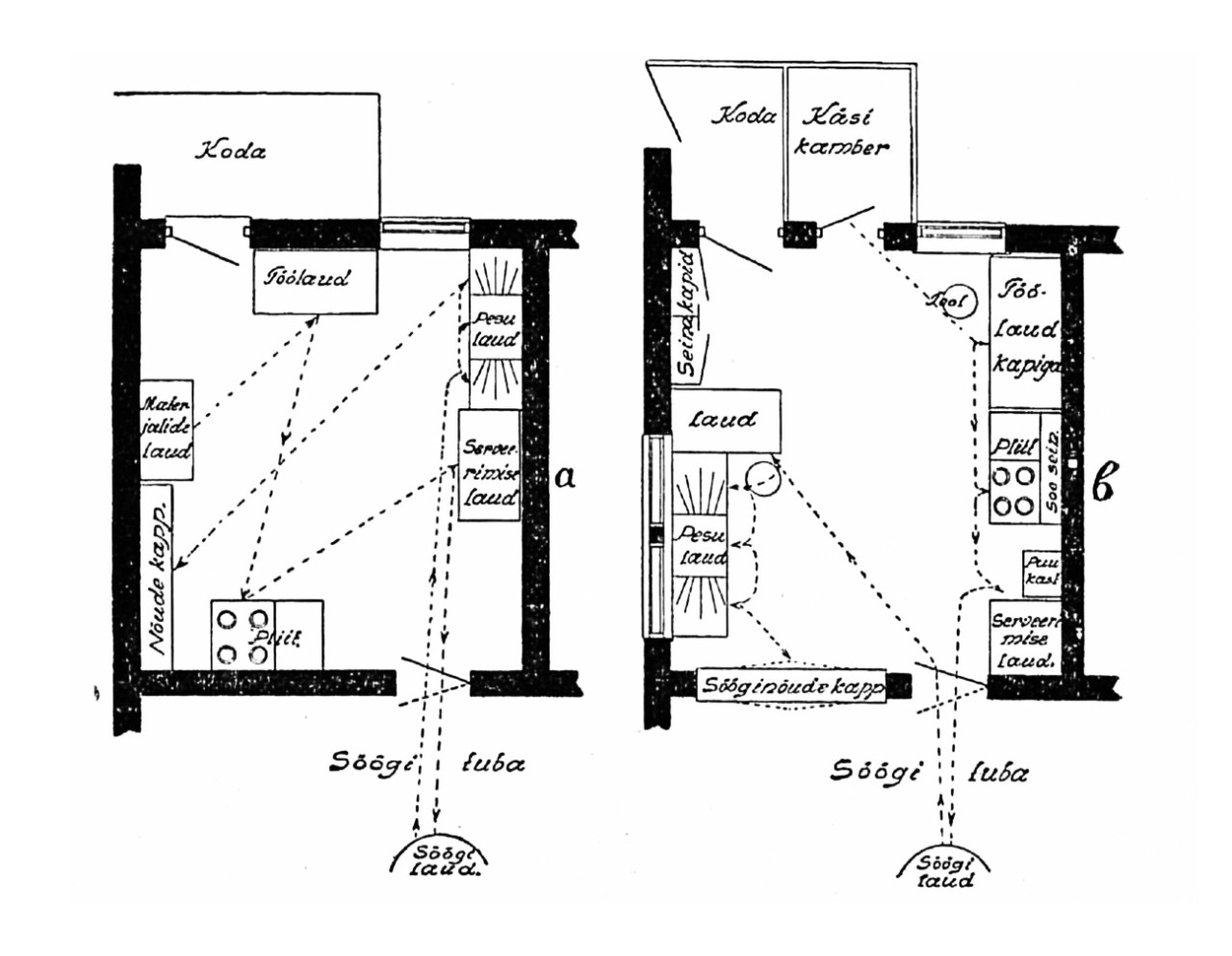

In 1922, The New Housekeeping was published in German (Die rationelle Haushaltführung, translated by Irene Witte) and became a bible for both housewives and avant-garde architects. Through the German cultural space, the ideas of domesticated Taylorism spread around the world. The permanent exhibition of the Estonian Museum of Applied Art and Design features two enlargements of Frederick’s kitchen plans before and after rationalisation, which were published as an illustration accompanying an article in the 1930 May issue of the magazine Taluperenaine (The Farmer’s Wife)6 (Figure 1). The marked down trajectory of the housewife with a dotted line has become iconic, as if giving evidence of the almost scientific reasoning behind every step and marking the end of going unnecessarily back and forth. However, when drawing her dotted lines, Frederick did not consider the simultaneous execution of several activities (e.g., preparing several dishes at the same time) or the possibility of several people operating in the kitchen at the same time. Despite these shortcomings, her space planning principles have become the cornerstone of effective kitchen design.

A further development of Frederick’s principles and one of the most important prototypes of modern built-in kitchen furniture is a kitchen project developed in 1926 by the architect Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky for social housing in New Frankfurt. Lihotzky dictated the housewife’s every step, designing the kitchen accordingly with furniture and the latest technology using, for example, appliances completely unfamiliar to the common man at the time, such as the gas stove, steaming pot, electric light, ironing board and a rotating stool designed to ‘prevent varicose veins’.7,8 Her kitchen design based on socialist ideas reflected the modernist maxim ‘form follows function’. The architectural historian Susan R. Henderson has pointed out that, unlike the projects of the ‘form and style’ architects, Lihotzky’s work, which focused on improving the quality of life of the working man, was recognised by the design historians only posthumously.9

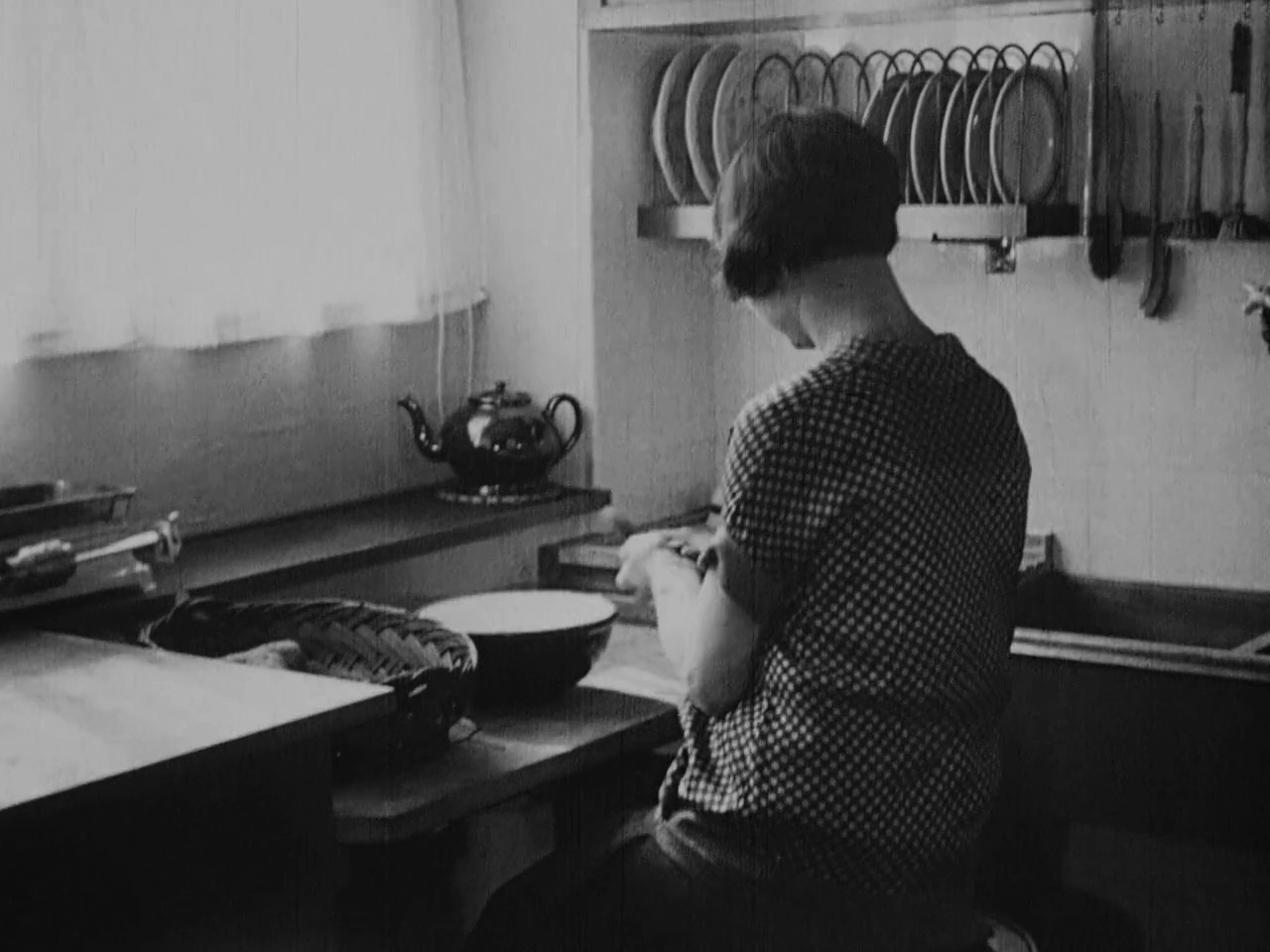

The film Frankfurter Küche (directed by Paul Wolff, 1927) that popularised Lihotzky’s extraordinary design, fought for the sympathy of the potential users for enlightening purposes, while using the prevailing techniques from commercial advertising. The first part of the film demonstrates the tiresome routine taking place in the traditional kitchen, while the second part exemplifies the easy workflow in the new Frankfurt kitchen. The last frames of the film show the housewife’s moving trajectories marked on a plan in Frederick’s style. The ‘before and after effect’ is further enhanced by the contrasting female characters. The lady working in the traditional kitchen resembles a Victorian era domestic servant. She is wearing a long, old-fashioned skirt with an apron, her hair tied back in a bun. The protagonist of the second part of the film, however, is an emancipated young lady wearing a short dress and a modern haircut (Figures 2–5). By drawing a connection between the modern clothes and the new kitchen furniture can be seen as a premonition of the future ‘styling culture’: “that implies progress, novelty, and sophistication, highly valued qualities in our society.”10

Figures 2–5. Housewife in a traditional kitchen. Excerpts from the film Frankfurter Küche (directed by Paul Wolff, 1927) <https://www.filmportal.de/video/die-frankfurter-kueche-1927> [accessed 05.03.2024]. Images: Screenshots by author

Already in the 1930s, some elements of the modern kitchen furniture implicitly became symbols of efficiency. A shift in paradigm can be noticed; for example, in the film Die neue Wohnung (New Living, directed by Hans Richter, 1930) promoting the achievements of the Werkbund. While in Frankfurter Küche the focus was on detailed work done in the kitchen (peeling vegetables, throwing out garbage, heating food, washing dishes, etc.), then in Richter’s film the exemplary kitchen is already represented by the sliding doors of the kitchen cabinets, the drawers and a folding table on wheels that seem to move almost as if by themselves. The visual sequence created with the help of animation gives the impression that in a well-planned and technically well-equipped kitchen the workflow happens as if by itself, without the direct interference of a person. Hiding the work that takes place in the kitchen imperceptibly became the norm in modern kitchen representation, still used in advertising and kitchen photography today.

After the Second World War, the kitchen area became bigger, new finishing materials emerged and kitchen appliances became cheaper, and thus more accessible to the general public. The open plan kitchen regained its popularity in the 1960s and 1970s.11 The isolated work space was turned into a presentable open space that allows communication with guests.12 That was also the time when kitchen furniture and appliances lost their initial industrial aesthetics, as the consumers no longer tolerated a connection with factory work.13 Smooth surfaces, streamlined forms and cheerful colours were used to make one forget the daily grind and instead fantasise about the carefree lifestyle of the leisure class. The kitchen island was added to the kitchen plan. In terms of its function, the kitchen island does not differ from Lihotzky’s kitchen worktop, but it takes up more floor space. This lets the person working in the kitchen enact the role of a TV show chef, even when reheating pre-prepared food. Playfulness and performance are key elements of the stylised kitchen.

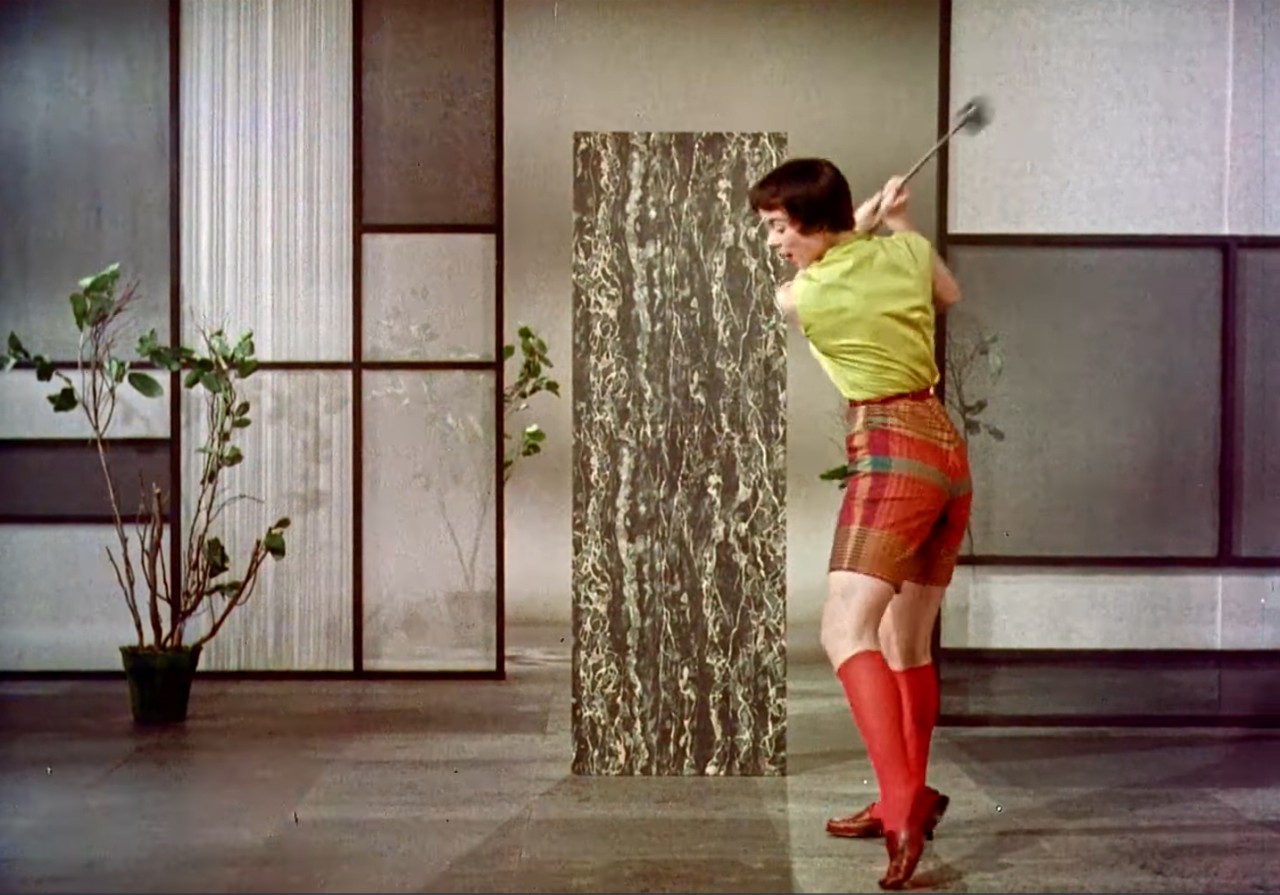

Although the kitchen is a place primarily meant for cooking, food only appears in the images of an exemplary kitchen mostly in the form of an artificially staged still life consisting of flowers, fruits, candles, etc. One might think these elements serve the same purpose as they did in historical paintings, hinting at the riches of the commissioner; that is, demonstrating “what gold or money could buy”. 14 The figure of the housewife in the kitchen interior no longer resembles the kitchen-factory worker, but the stereotypical “perfect hostess (spectator-owner’s wife)” or sex-object.15 Elegantly dressed, she welcomes either guests or the husband himself who has returned from work. One example full of the clichéd techniques of ‘styling culture’ is the General Motors promotional film Design for Dreaming (directed by Victor D. Solow, 1956). A kitchen with a dancing housewife (Thelma Tadlock) is presented as an object of desire, similar to a Buick, Chevrolet, Corvette or Cadillac (Figures 6–8). A cake decorated with whipped cream and candles is ready at the push of a button, while the sexy female protagonist changes outfits related to the leisure class’ recreational activities; that is, slipping into the roles of a tennis player, golfer and beachgoer. The kitchen on the other hand is presented as a conditional architectural form wrapped in shiny steel, plastic and glass (Figure 9).

The forecited examples may seem outdated. Nonetheless, the marketing methods of kitchen design have not changed much. The kitchen design principles have basically remained the same since the Frankfurt kitchen. Functionality and efficiency are considered integral features of the modern kitchen, assured by ergonomic solutions developed a hundred years ago. The only varying components are the surface area, materials and style. In order to market these, routine kitchen work and cooking with its associated sounds, smells and tools have been marginalised. This phenomenon can be linked to the desire to imitate the carefree lifestyle of the elite, which lacks the obligation to cook or clean the kitchen. Similar to the fast fashion brands, the cycles in kitchen fashion are becoming shorter. Analysing the real needs of the kitchen user and social design have become a thing of the past. The kitchen design serves the styling culture, driven by images that encourage consumption. Could we offer an alternative to this kind of design holdover? I would assign this task to the critical designers who might dare to run counter to the overproduction and overconsumption driving modern culture.

References

- Advertising text <https://krauskoogid.ee/> [viewed 03.03.2024]

- Advertising text <https://fmpdesign.ee/category/marmor-tasapinnad/> [viewed 26.02.2024]

- Advertising text <https://www.tootasapind.ee/marmor.html> [viewed 26.02.2024]

- Frederick, Christine, The New Housekeeping. Efficiency Studies in Home Management (New York: Doubleday, 1919), title page.

- Rutherford, Janice Williams, Selling Mrs. Consumer: Christine Frederick and the Rise of Household Efficiency (Athens: University of Georgia Press, 2003), p. 105.

- Martin, I., Köögi sisustusest, Taluperenaine: rahvalik kutseajakiri, 1930, No. 5 (May), p. 126.

- S. R. Henderson, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. A Career in the Design Politics of the Everyday, The Responsible Object. A History of Design Ideology for the Future, edited by M. Van Helvert (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2016), p. 70.

- P. Overy, Light, Air and Openness (London: Thames and Hudson Ltd, 2007), p.95.

- S. R. Henderson, Margarete Schütte-Lihotzky. A Career in the Design Politics of the Everyday, The Responsible Object. A History of Design Ideology for the Future, edited by M. Van Helvert (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2016), p. 84.

- M. van Helvert, Design for Consumer Society, The Responsible Object. A History of Design Ideology for the Future, edited by M. Van Helvert (Amsterdam: Valiz, 2016), p. 114.

- D. Clarke, Open Plan gone Mad?, Sanctuary, 16 (2011), p.86.

- A. Surmann, The Evolution of Kitchen Design: A Yearning for a Modern Stone Age Cave, Culinary Turn: Aesthetic Practice of Cookery, edited N. van der Meulen (Transcript Verlag, 2017), p. 54.

- A. Forty, Objects of Desire (London: Thames and Hudson, 1995), pp. 207–221.

- J. Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: BBC, 1977 ), p. 99.

- Ibid., p. 138.