Published on 14.06.2024

Hannah Segerkrantz is a designer whose practice combines the notion of agency with the re-definition of what we address as our ‘surroundings’. With an interest in the intersection between architecture and radical ecologies, her approach to research is environmental, sensorial and contextual. Whether exploring the cultural background and gestures of architectural materials, or studying the relations between objects, people and local traditions, she offers tools and means for bridging our connection with the environments we inhabit. hannahsegerkrantz.com

Landscapes as a typology specific to each location have been something that humans arrived at. As environments, they are in constant change, which can be sped up as a result of our activity within them, but nevertheless, despite our behaviour they are never static places. Hence, the question of maintenance arises – is it our role as self-imposed ‘controllers’ of the environment to maintain the way our surroundings have always been, or could we allow nature to just be?

As Tim Ingold put it so well, we should “move beyond the sterile opposition between the naturalistic view of the landscape as a neutral, external backdrop to human activities, and the culturalistic view that every landscape is a particular cognitive or symbolic ordering of space. I argue that we should adopt, in place of both these views, what I call a ‘dwelling perspective’, according to which the landscape is constituted as an enduring record of – and testimony to – the lives and works of past generations who have dwelt within it, and in so doing, have left there something of themselves.”1 In regard to giving care and attention, maintenance does not necessarily have to mean that we should return nature to any particular previous state, or transform it into something new. Instead it is an ongoing process, a presence, a certain sense of attention that is only possible while existing with(in) the environment. It is about listening and understanding what could be best, and often that is very little. Maintaining a landscape is about maintaining relationships.2 Therefore, it is about time we gave up the false assumptions of human mastery over the environment, which is not about abandoning our relationship to land or place, but reinforcing relations by redefining them anew.

If we approach maintenance through Ingold’s dwelling perspective, our activities become maintenance, whether intentionally or not. What we do within and towards our environment inevitably affects it, and it is here that we can choose to approach the land with or without care, with the heart, focusing on perspectives of cohabitation and commons, or with the capitalistic and progress-driven ego. In either way, we are leaving a mark of our time. In this context, care could offer a useful entry point to navigate the space of relating to the landscape. To care is to feel concern or interest, attach importance to something, and care is attention given, the tending to, or the provision of what is necessary for something or someone. In dictionaries, care is mostly defined as a sentiment of concern and responsibility, a process of protecting, covering needs, or the act of maintenance.

How can we tend to nature in a way nature would like to be tended to? This is a question I have been asking myself since August 2022, during the Academy of Margins summer school organised by the Robida Collective. Throughout one week, each morning we carried out ‘useless acts of care’, an initiative guided by Ola Korbańska – we’d weed the narrow streets of Topoló and day after day make our way down towards the river, organising leaves on the forest floor, releasing trees from brambles, or cleaning stone walls from moss, all the while being read out loud essays by Tim Ingold. Questions arose like how do we relate to the landscape, or what does it mean to care for our surroundings, which ignited various discussions. In the Robida glossary, the term ‘useless care’ is defined through gestures and practices that barely make any difference or change the course of the landscape’s transformation. Rather, it is seen as a caress towards the surrounding environment, speaking of collaboration and co-habitation, rather than of control and use of the land. Small gestures of useless care could represent a possible feminist approach to abandoned landscapes to which we feel a certain affection.3

It was there that I realised that it’s a question of the ego wanting to show more care to feel better about taking. Perhaps being grateful and present is already enough, perhaps it is not about taking less, rather about allowing oneself to enjoy and take without the lingering feeling of guilt? In the context of Topoló and its surrounding landscapes I knew it was impossible to exist in the village without being temporarily involved in the community, which took away the pressure of having to contribute – instead contribution became an implicit act of care. Similar perspectives are implemented in the essay Serviceberry written by Robin Wall Kimmerer, where she proposes that gratitude is so much more than a polite “thank you.” It is the thread that connects us in a deep relationship, simultaneously physical and spiritual, as our bodies are fed and spirits nourished by the sense of belonging, which is the most vital of foods.4 If our first response is gratitude, then our second is reciprocity – to give a gift in return. These gifts can very well be the above-mentioned small gestures of (useless) care, tending to nature, the community, or even writing about it, to invite others into the same relationality.

Developing this stream of thought towards the caretakers of the planet, I have to wonder whether it is only women who are able to care, or whether it’s a collective capacity disregarding gender, sex and race? In her book Stolen Harvest, Vandana Shiva highlights that it’s often women who are most severely affected by ecological disasters, as they are responsible for gathering food, collecting water and carrying and caring for children.5 Both Shiva, an Indian scholar, environmental activist and ecofeminist, and Carolyn Merchant, an American ecofeminist philosopher and historian of science, are critically contributing to the global discourse on ecofeminism by highlighting the deleterious impacts of patriarchy on the domination of women, and colonialism and sciences on the degradation of the environment as well as indigenous knowledge. As further stated by Timothy Morton, “putting something called Nature on a pedestal and admiring it from afar does for the environment what patriarchy does for the figure of Woman. It is a paradoxical act of sadistic admiration.”6

Deriving from the theory of women as gatherers,7 carriers and caregivers, the more ‘essentialist’ ecofeminism advocates for the perspective of woman as Mother Earth or goddess, reclaiming the women-nature connection as an ability to care better, mainly due to women’s reproductive capacities. The ancient identity of nature as a nurturing mother links women’s history with the history of the environment and ecological change – the female earth was once central to the organic cosmology that was later undermined by the Scientific Revolution.8

But both concepts of nature and women are historical and social constructs. In her work The Second Sex, Simone de Beauvoir, a French existentialist philosopher and feminist, argued that women are not born but rather become women through the social construction of gender roles, stating that these roles limit women’s freedom and opportunities, and that they stifle their creativity and potential. Juxtaposing the movements of ecology and feminism could suggest new values and social structures, based not on domination of women and nature as resources, but rather on the maintenance of environmental integrity, returning to the feminine in terms of practices and knowledge. Therefore, if we would opt for care and cooperation instead of the currently common aggressive and dominating behaviours towards nature, we would benefit both landscapes as well as women.

My own practice is driven by the mission of bringing harmony between the planet and the people, a goal so big I sometimes wonder how I can ever even get close. It’s definitely not something that would scream from my portfolio – my acts are implicit, my work careful, so as to not impose my stream of thoughts upon the viewer, but unconsciously guide them towards being more in tune with their surroundings. When we blame another for not being with the environment in a certain way that we ourselves consider ‘good’ or ‘sustainable’, we create resistance over receptiveness. This way we can never return to the sense of being one with nature.

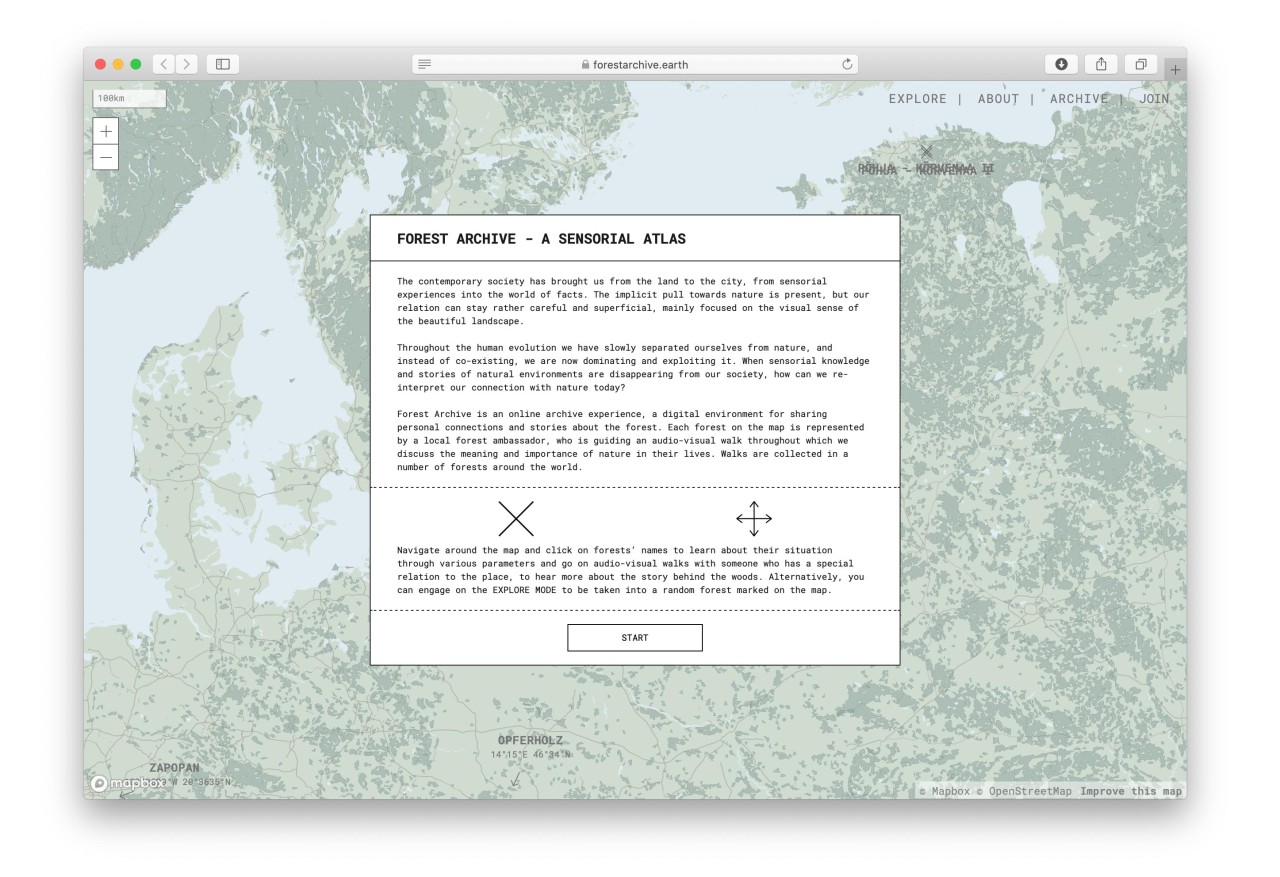

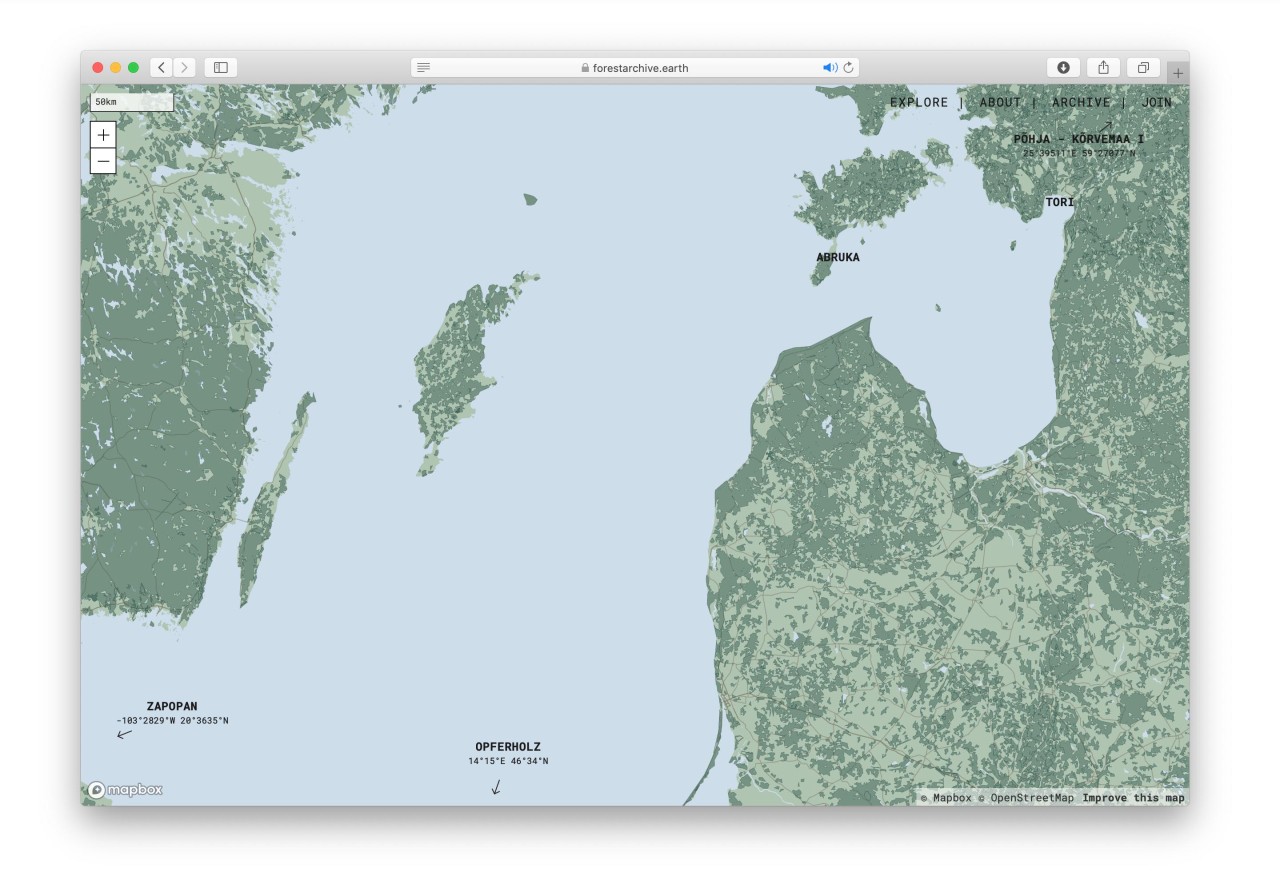

In 2020, I created a platform titled forestarchive.earth, where I went on forest walks with people. It was the beginning of the pandemic, and all of a sudden the usual syndrome of having unlimited freedom of movement and not enough time was reversed – from that point onwards there was an unlimited amount of time with total restriction of movement. I chose to be stuck in The Netherlands, with little to no access to real nature, all the while receiving images and videos of sunsets from my parents, who spent a lot of time walking outside. On one random spring day in 2020, I called a friend who was walking in the forest. He constantly interfered with our call with notes such as “I just stepped into the stream…” or “I’ve never seen this mushroom grow here before!” or “this cloud looks like a dragon”, which felt like a teleportation to an utterly familiar context – the woods of Lahemaa National Park. From that call onwards, I started interviewing people who lived in close proximity to nature, about their experience of oneness. If my work usually guides me to researchers, scientists and ecologists, this time it was normal people, experts of their own experience. All the walks were recorded by the walker attaching their phone to their hat with two rubber strings, and their view guiding our discussion.

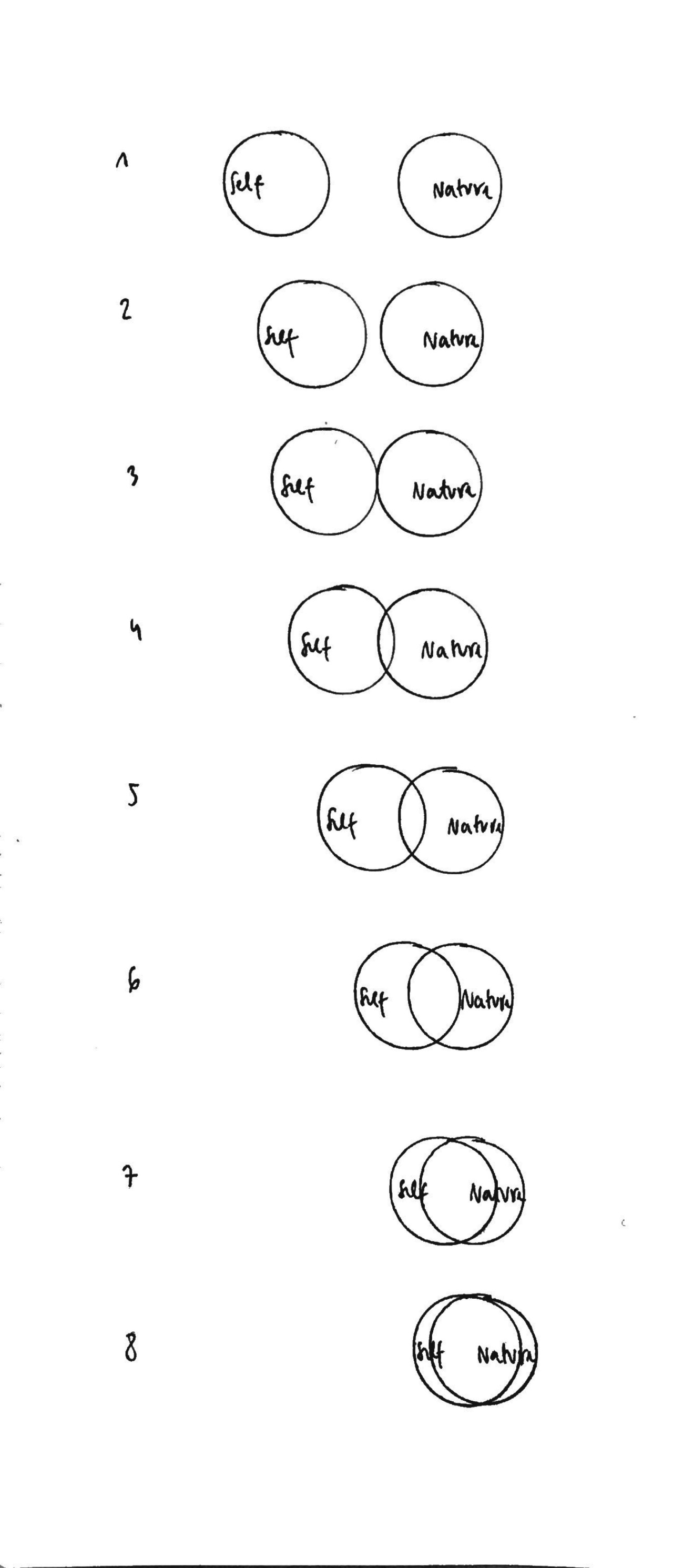

Through digitalising the forest and creating an interface for walking in nature, the aim of Forest Archive was to help people understand the value of existing together with nature and through the shared stories, rediscover their intuitive connection with their surrounding environment. As said by Andy Goldsworthy, we often forget that we are nature, that nature is not something separate from us. So when we say that we have lost our connection to nature, we’ve lost our connection to ourselves.

It’s not just land that is broken, but more importantly, our relationship to land.9 The assumption of human mastery over nature must be courageously confronted to make way for other practices to emerge. The references above serve as proof that I am not alone in believing that there are other ways of living with and relating to the landscape, and thus designing, growing and building with an augmented sense of responsibility and care.

References

- Tim Ingold, ‘The Temporality of the Landscape’, World Archaeology, 25, 2 (1993), pp. 152–174.

- Antonio Sotgiu, Maintenance in the Robida Glossary <https://robidacollective.com/> [accessed 6 March 2024].

- Vida Rucli, Useless Care in the Robida Glossary <https://robidacollective.com/> [accessed 6 March 2024].

- Robin Wall Kimmerer, ‘The Serviceberry’, Emergence Magazine, 2022. <https://emergencemagazine.org/essay/the-serviceberry/> [accessed 6 March 2024].

- Shiva Vandana, Stolen Harvest: The Hijacking of the Global Food Supply (Cambridge: South End Press, 2000).

- Timothy Morton, Ecology Without Nature: Rethinking Environmental Aesthetics (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 2009), p. 13.

- Elizabeth Fisher, Women’s Creation (New York: Anchor Press, 1979).

- Carolyn Merchant, The Death of Nature (San Francico: Harper & Row, Publishers, 1980).

- Robin Wall Kimmerer, Braiding Sweetgrass (Minneapolis: Milkweed Editions, 2013).