Published on 14.06.2024

Tõnis Jürgens is an artist and writer based in Tallinn, who works mainly in the medium of film and video essays. He holds degrees in cultural theory from Tallinn University (BA) and new media from the Estonian Academy of Arts (MA). Additionally, he has studied photography at the Academy of Arts, Architecture and Design in Prague. He is currently a PhD candidate and guest lecturer at the Estonian Academy of Arts. His artistic research practice involves themes like sleep tracking and surveillance capitalism. He is interested in the relationship between sleep and death and the measuring of something undefined.

“Sleep thou, Sancho,” returned Don Quixote,

“for thou wast born to sleep as I was born to watch.”1

Sleep and the feeling of security are clearly linked. Sleeping is one of the most vulnerable and private states where we can place ourselves, and the bedroom is a refuge where we can remove ourselves from the world and the everyday. In truth, houses – and we could even say the whole of society – are created for people to sleep as well as possible.

According to one theory of evolution,2 the first primates, who descended from trees to the ground to sleep, started experiencing substantially more REM sleep. This, in turn, contributed significantly to the development of their brains. Those who rest in trees cannot sleep as deeply since they are threatened by the constant danger of falling. Sleeping on the ground, however, they have to find new methods of protecting themselves from attackers. The cognitive and emotional development resulting from deep sleep allowed the primates sleeping on the ground to devise new and inventive ways of making their sleeping environment more secure; more REM sleep, in turn, brought about even faster development of the brain – and so forth.

The sleeping environment is therefore an essential topic. The spatial philosopher O. F. Bollnow3 states that the notional hearth of every home is actually the bed, since this is the place where we begin our days, where we wake up to do our deeds, and where we settle down at the end of the day. If wakefulness denotes facing the external world, then sleep usually denotes the opposite: a temporary and regular end of activeness, surrendering control, establishing a pause to one’s own world. Some thinkers have posited that sleep is, in a way, a routine exercise for death. It is an everyday pause or a hiatus, which we take in a space which is the most personal to us and which acclimatises us slowly with the idea of the “infinite hiatus”.

This delineates the duality of sleeping and wakefulness: we sleep to live and live (in the end) to sleep. Sleeping and wakefulness have historically been seemingly two sides of the same screen: they have a relationship, but they are clearly separated. I am mainly interested in how our approach to sleep has changed over the last centuries and has actually become increasingly “active”. In parallel with this, dualities like sleeping/wakefulness, private/social have become intertwined. The external world and the hegemony of efficiency has secretly infiltrated the private sphere of the bedroom and sleeping, and in recent years “correct” sleep has become part of a larger social debate.

Ever since my master’s studies at the New Media Arts programme of the Estonian Academy of Arts in 2014–2016, an image haunts me: I’m lying at night in my bed and am observing the headlights of the cars passing below on the street; how they flicker, stretch and fade on the walls and ceiling of the dark room. At the beginning of my studies, I toyed with the idea of constructing a life-sized simulacrum where the exhibition visitor could lie in bed observing the headlights of the passing cars in a similar manner. At that time, however, this idea lacked most of the necessary conceptual ballast: it seemed merely a cool idea. In the end, I used another theme for my master’s thesis: the theory section was based on the history of transhumanist philosophy and I took a critical look at technological immortality. All of this didn’t have a place for light spots flickering on ceilings (in truth, I couldn’t see the connection at that time) and this image was set aside for a while.

Years later, I’m in the Academy’s PhD programme examining the self-care industry, the digital measurement and tracking of sleep and am building stage set bedrooms. Somehow the image of passing car headlights keeps returning to me again and again. I still don’t know how to explain this to myself, but the cold light penetrating the darkness of the bedroom – and the sleepless tracking of those lights – has some sort of a connection with measuring sleep, the disappearance of privacy and the theme of ante-mortem limbo.

But first, a short historical overview of the handling of sleep on the scale of passive and active.

Before the 20th century, sleep was mainly seen as a physically passive state: disappearance into some mystical and ephemeral void which is inaccessible to those who are awake and which could only be mediated to others by the sleeper after they had returned to consciousness. At first glance, sleep seems very similar to death. Therefore, it is probably no surprise that even in the 19th century people were sometimes buried in “safety coffins” equipped with little bells which could be rung by a person who accidentally woke up inside a casket. The methods of that time for identifying death (or sleep) left something to be desired compared to today and there were numerous stories about being buried alive. This is why solutions were developed to fight the fear of being buried when somebody was sleeping: it had become especially pressing due to the repeated cholera pandemics during the century and also thanks to Mary Shelley’s extremely popular novel Frankenstein.

Only in the 1950s did it become clear thanks to the electroencephalogram (EEG) and breakthroughs in scientific research that sleep is, in fact, not a passive state and a mere phantasmagorical void which temporarily subsumes the sleeping subject. Measurements of the brain activity of sleepers showed that during sleep the brain is exceedingly active in the bioelectric sense. Compared to psychoanalysis, which had found its footing in the beginning of the 20th century and which interpreted dreams as stock material that had been brought back from an obscure state, the empirical study of sleeping allowed us to make significantly more tangible and convincing generalisations about the sleepers. Besides, it took place in real time, while they were sleeping. Thanks to EEG, the different phases of sleeping in the brain activity of sleepers were mapped. It became clear that, in a practical sense, sleeping is something completely different to a mere absence of wakefulness. These discoveries led to the founding of a completely new area of science: the laboratorial and data-based research of sleep.

The laboratories of sleep are essentially very unintimate and the research of sleep that takes place is, one might say, like oneiric voyeurism. The sleepers are covered with the electrodes of measuring equipment, they are observed and filmed while they are sleeping, information is gathered about different involuntary actions made during sleep, and afterwards all the data gathered through the machines and observations is thoroughly analysed. (In other words: while the informants sleep, the laboratory technicians are awake observing their sleeping.) As an intern and participatory observer at a sleep laboratory, Julia Vorhölter4 has coined the term “techno-intimacy”: the sleep of the person sleeping in a laboratory is in intimate contact with external technological (measurement) instruments like electrodes, cables, masks, etc. Using the technological research of sleep, we will become (subjectively) more familiar with ourselves, but this happens through the (seemingly objective) mediation of machines. This, of course, means that machines which are used to research sleep play a very important role in shaping the research results. One important aspect of the work done at sleep laboratories is getting the sleepers accustomed to the presence of unwieldy machinery, to make the process of measuring them in the privacy of their sleep with various instruments as comfortable and normal as possible.

When I was an exchange student at the Photo Studio of the UMPRUM University in Prague in 2021–2022, I met my fellow student Matěj Kos whose master’s project contained themes which I was interested in: scenography and video art; creating the atmosphere of the living space of a fictitious person and telling a story about them using a room that had (temporarily) been left empty. I told Matěj of the idea about passing headlights and we decided to create a joint work for evaluation during the spring semester, which became the short film titled curtains are shut, the furniture is gone9 (2023, 3′36″).

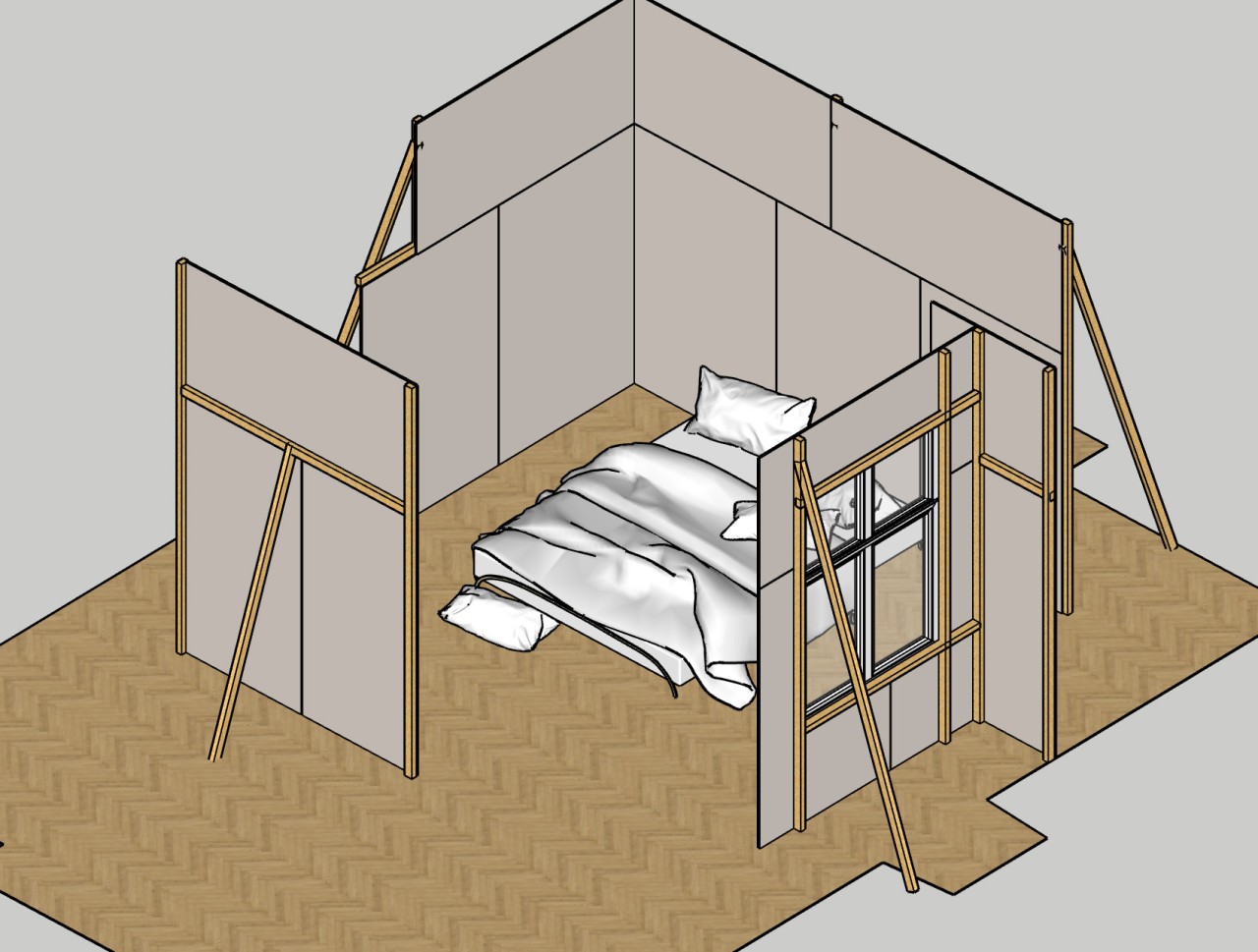

For this work, we constructed the set of a bedroom inside a former pool hall in the centre of Prague and later filmed the room for the work. To construct the room and to create the atmosphere, we used simple construction materials and methods: cheap wooden beams, plasterboard, textures printed on paper and other clearly bogus elements together with “real” objects. We painted the texture of wooden parquet onto a cardboard floor; a smaller cardboard piece was sprayed with satin black paint and thrown onto the bed to look like an iPhone that has been left behind; onto walls we glued electrical sockets printed on paper; we constructed a stand for a book and a chair out of random pieces of wood; we folded and glued an imitation of a half full coffee cup and flip flops left in the middle of the floor out of paper.

For filming, we used photography spotlights and movable mirrors to create an illusion of street lamps and passing headlights. The accompanying narration, which is only presented as subtitles (the audio background of the film consists of Prague traffic noise recorded from the window of my bedroom), offers an everyday story about a young woman alternating between anxiety and apathy, who is smoking in her bedroom (which is unusual for her) while she is thinking, looking at the flicker of passing lights on the wall.

Immediately after the joint work by me and Matěj was completed and presented to the evaluation committee at UMPRUM, I started making a “meta-film” or a making-of work for the recently completed video. This became the video essay A Practice for Surrender (from here on shortened as APFS) (2022, 12′49″). It is “meta” because it explores from my perspective (the perspective of artistic research) the reasons for creating the work curtains are shut, the furniture is gone, using certain excerpts from the film as visual material.

The main research theme of APFS is the simulacrum of passing car headlights. The film maps my exploratory journey towards the visual of headlights. One part of this has been collecting similar visuals from various feature films. Among these are films like Barfly (1987), Requiem for a Dream (2000) and The Big Sleep (1946).

In APFS, the light cast from a window or some other implied niche into an enclosed space becomes also a metaphor for (illusory) recognition. In the video I talk as the narrating voice about my mistaken understanding that the eyes of a crab are physiologically like caves: tiny openings in the exoskeleton of the being into which the light is projected and where it re-fractures in the same way as in a camera obscura. In reality, as I learned later, the physiological composition of the eyes of a crab is completely different. However, bound by this mistaken understanding, I had been thinking for a long time that crabs have an inexplicable but tight connection to my research, which will reveal its nature at the end after sufficient contemplation. (This actually did happen.)

My illusory and self-ironic understanding along with the eyes of the crab themselves accompany the rest of the film as a metaphor for a Platonic cave. The eyes of the crab, screens, windows, arrival of sleep and passing headlights will become a uniform, overlapping and extrapolating visual image in this video essay through which I as the researcher am trying to comprehend my chosen theme. This encompasses the video essay itself, the following chapters of the research as well as my personal contemplative patterns. This is followed by an impulse to “capture” passing headlights as a visual in an artificial environment created following my own volition. Which in the end is the constructed film set/bedroom.

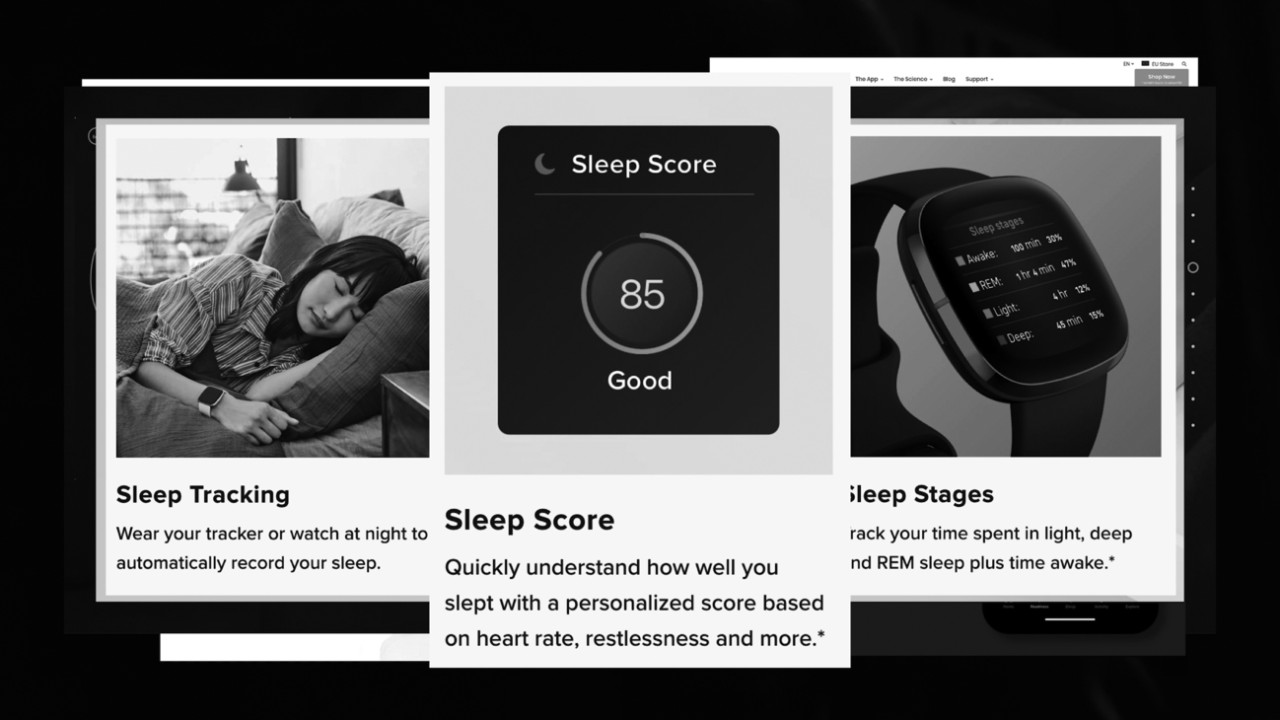

Today, the empirical tracking of sleep has become possible and popular also outside sleep laboratories, in the privacy of domestic bedrooms. This is especially apparent in the contemporary self-care industry, which has managed to subtly bring together sleep, the feeling of safety and surveillance society. Over the last few years, sleeping has become a societal and moral issue: the media talks about an expanding crisis of sleep and the optimisation of sleeping habits. During stressful and anxious times, it is important to be aware of sleep hygiene in order to be a healthy and clear-headed citizen. The opposition argues, however, that this way of thinking makes sleeping part of the general social credo of productivity. As the author of The Care Crisis Emma Downling5 states, taking care of oneself has become increasingly privatised and an activity that is strongly recommended because it raises the general productivity of society. Second, we have to take care of ourselves because nobody else will do it for us. British cultural theorist Mark Fisher6 has fittingly called it “the privatisation of stress”.

The self-care industry offers individual consumers numerous wearable and nearable (close to the body) tracking devices for taking care of themselves. Smart watches, rings, bracelets, blankets, pillows and speakers – the immense assortment of consumer tracking devices has made measuring and inspecting one’s sleep possible outside uncomfortable and clinical sleep laboratories. Smart devices equipped with different sensors track the sleeper’s pulse, blood pressure, movement, sounds made during sleep and other characteristics that allow us to make generalisations based on the data; how to raise the quality of your sleep, how to shape your everyday habits in order to achieve better sleep, how to optimise your bedroom.

Zillien, Wettmann and Peper7 talk about the tracking of sleep using “domestic” resources as an experimental activity which strives towards reducing everyday uncertainty. Science plays a larger role in shaping the public discussion than ever before; however, as a result of the overabundance of information, people are today more sceptical about science. Monitoring our sleep using smart devices allows us to take the control of our sleeping and living habits into our own hands and to experience practical results for ourselves. (“Self knowledge through numbers” is the slogan of the global self-tracking movement Quantified Self.8) The self-care industry allows us to actively interfere in our sleep based on data in order to improve sleep hygiene and health in general.

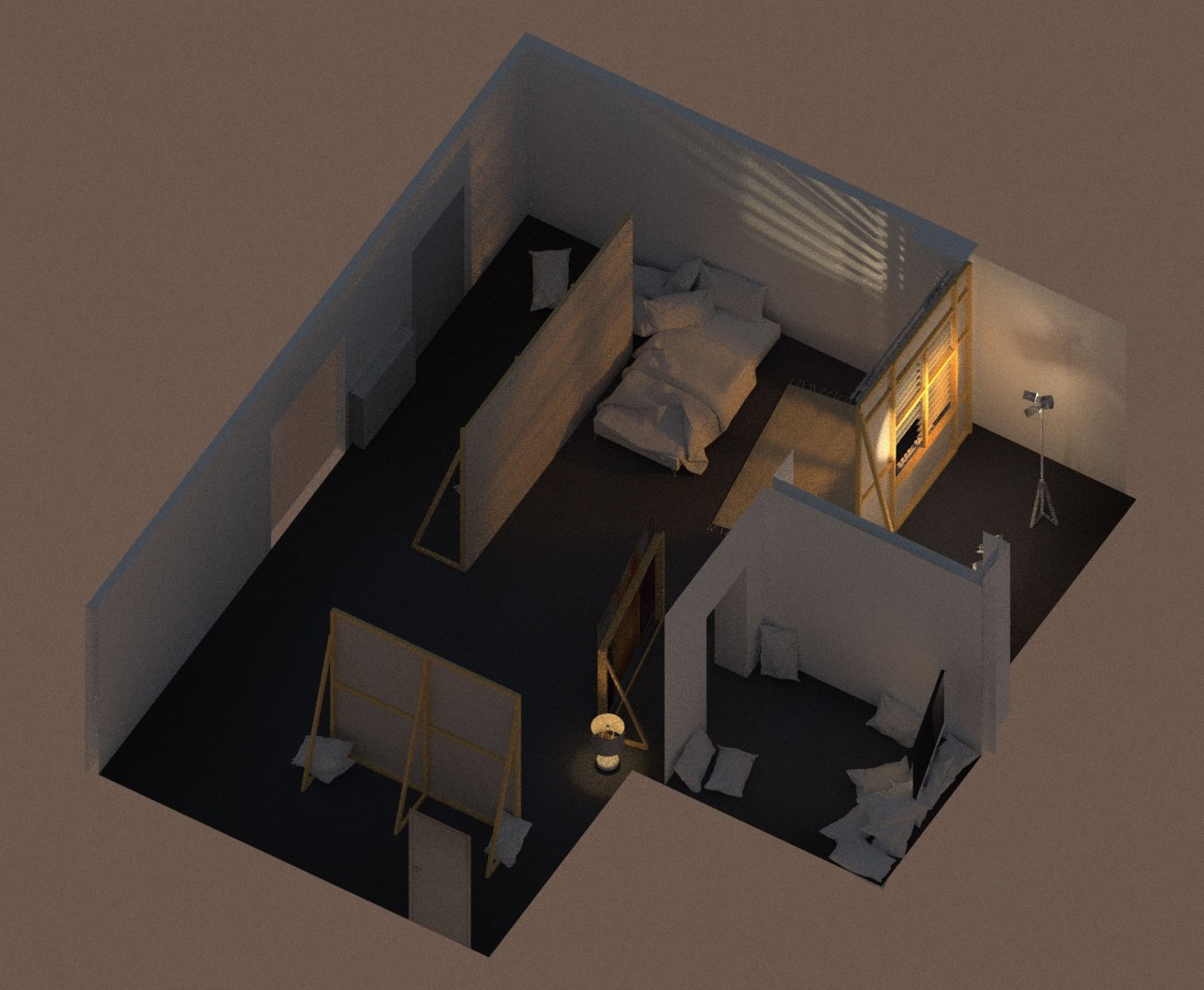

This work found an even more material form at the installative exhibition A Practice for Surrender at Vent Space project space (20–30 September 2022). For the exhibition I constructed an environment similar to the film set in Prague: fake walls supported by wooden beams, the texture of a carpet printed on paper, a partition wall covered with a misleading texture of a wardrobe, pillow cases filled with sand. Through the window of a partition added to the gallery, a warm light similar to street lamps shone into the room with the harsh sweeping illumination from a flatbed scanner cutting through it at regular intervals as if car headlights had been reflected into the space. During the filming of APFS, I used the scanner in a similar way for “scanning” the various corners and objects of my bedroom.

In the video essay I talk about the artificial nature of contemporary sleep. On the one hand, it is represented by Arnold Schwarzenegger’s world-famous sentence about simply “sleeping faster” since there are not enough hours in a day to accomplish everything. To me, Schwarzenegger’s joke with its accelerationist undertones goes strongly together with the ideology of the digital tracking of sleep and self-optimisation whereby the crisis of sleep could be solved by data measurement and using time as efficiently as possible. Sleep is enlisted in the service of wakefulness in order to be as productive as possible outside the bedroom. In many ways, this idea is controversial since streamlining sleep can create the pressure to sleep better, which, in turn, might lead to greater sleeplessness.

The other extreme of the artificiality of sleep is represented in my video essay by the protagonist of Ottessa Moshfegh’s bestselling novel My Year of Rest and Relaxation. When she is beset by grief and a loss of the meaning of life, she seeks help in a motley collection of prescription medicines, experimenting with a variety of antidepressants and tranquillisers in order to sleep as long as possible to replace reality with dreaming, get lost in sleep and to emerge from its dark cocoon as a new human being.

The above-mentioned techno-intimacy has therefore penetrated our homes and our bedrooms. Under the guise of measuring and optimising sleep, the makers of smart devices collect data from the sleepers into their data centres: the hours slept, changes of side, nocturnal snores and private mumblings ooze into the general data stream where they can be used to improve the user experience as well as for marketing new products. With the pretence of efficiency, control, sense of security and innovation, the self-care industry and digital self-tracking has furtively assisted in blurring the border between the privacy and publicity of sleep.

In parallel (and maybe also paradoxically), the focus of my research has shifted from the ethical and philosophical discords of the digital measurement of sleep to a broader topic which can be called “the disappearance of the subject”. As the Egyptian philosopher Haytham El Wardany10 contemplates, sleeping subjects don’t actually exist for themselves:

“[Sleep] is impersonal. We don’t know who is doing it. Or rather, the one doing it is always an absent party.

Sleep becomes personal after I’ve woken up.”

This is, of course, a purely philosophical approach to sleep and personalisation. Looking at it from the viewpoint of the science of sleep and neurology, the brain of a sleeper is exceedingly active during sleep. El Wardany’s interpretation limits personalisation or subjectivity to wakefulness: subjects disappear into their sleep to afterwards reappear again, but during the sleep they don’t exist for themselves. They do exist, however, for everybody else: for the people who are awake and for the machines that can observe the sleepers without them being aware of it. During the digital measurement of sleep, the sleeper is mediated to those who are awake by the data collected by tracking devices. The data, metaphorically, becomes an outline which delineates the subject who has otherwise dissolved into the unknown of sleep.

Using similar principles, I have identified for myself the empty bedroom as the symbol of a film set. It is something which allows for the rough delineation of the missing subject, similar to a sheet thrown on top of a vague physical mass. Emphasising that it is, in fact, a staged bedroom, “the set of sleep”, has been based on the idea of highlighting the illusory nature of film-like and dream-like qualities.

Sleep is a “necessary illusion” which moves the sleepers’ attention away from the fact that in their sleep they are under observation. Sleep is a smokescreen, which surrounds the sleepers who do not exist outside the sleep for themselves. The empty room is an implement of delineation pointing out the missing subject. It is actually a mental image of the subject’s inexistence, which is conveyed through the things and phenomena that are left behind by the subject: they are represented by the walls of the bedroom supported by thin wooden beams or the shadows disappearing under the fading artificial light on the walls. It is something that I don’t know how to imagine in any other way (at least not right now).

Broadly speaking, the polemics about the measurement of sleep – and self-tracking and optimisation in general – are about the confrontation between disappearing mysticism and encroaching pragmatism. In the self-care narrative, sleep has long ceased to be a passive zone where the sleepers can routinely disappear to avoid the everyday. Instead, sleeping has become an active ideological element in our twenty-four-hour cycle of production-(surveillance-)consumption.

Maybe the practical side of this artistic research points towards the aforementioned passive, pre-artificial sleep where the sleeper could unconditionally disappear, and that has nothing to do with efficiency or productivity. The walls of the bedroom supported by the beams do not only delimit the theoretical aspects of my creative research, but they apparently delimit me as well. Like a Don Quixote beset by nostalgia who tries to bring back the imaginary Better Times despite the inevitable onslaught of progress. Measuring sleep and the absence / emergence of the subject in the data has offered me a pretence. It has created the possibility of using spots of light captured inside bedrooms, and pillow cases filled with sand to jump over my own shadow. On some level the empty room therefore helps me to cope and come to terms with the inevitable disappearance of myself (and my subjectivity). Or, to paraphrase El Wardany, sleep is a long practice for surrender.

Viited

- Miguel de Cervantes, The Ingenious Gentleman Don Quixote of la Mancha, vol. 4, trans. John Ormsby (New York: Dodd, Mead and Company, 1896), p. 337.

- Matthew Walker, Why We Sleep (New York: Scribner, 2017), p. 82.

- O. F. Bollnow, Human Space, trans. by Christine Shuttleworth, ed. by Joseph Kohlmaier (London: Hyphen Press, 2011), p. 156.

- Julia Vorhölter, ‘Sleeping With Strangers – Techno-Intimacies and Side-Affects in a German Sleep Lab’, Historical Social Research, vol. 48(2) (2023), pp. 23–39.

- Emma Downling, The Care Crisis: What Caused It and How We Can End It (London, New York: Verso, 2021).

- Mark Fisher, Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? (Winchester: Zero Books, 2009), p. 19.

- Nicole Zillien, Nico Wettmann, and Frederik Peper, ‘Sleep Experiments. Knowledge Production through Self-Tracking’, Historical Social Research, vol. 48(2) (2023), pp. 157–175.

- <https://quantifiedself.com/about/what-is-quantified-self/> [accessed 13 March 2024]

- The title of the film is borrowed from the lyrics of Jubilee Street by Nick Cave & the Bad Seeds.

- Haytham El Wardany, The Book of Sleep, trans. by Robin Moger (Kolkata: Seagull Books, 2020), p 158.