Published on 28.11.2025

Annelies Thoelen is an art historian, curator, and educator. She is currently the coordinator of the newly established DesignPunt expertise centre at Design Museum Ghent, where she develops a platform connecting designers, researchers, and policymakers around contemporary design questions. She also teaches design history and theory at LUCA School of Arts. From 2018 to 2024 she was curator at Z33, House for Contemporary Art, Design and Architecture in Hasselt, where she organised exhibitions, including Fitting In (2022), and Healing Water (2023).

Curating is a verb that, in the art world, often carries a near-sacred connotation. In the fine arts, curating frequently means stripping away all external references. The artwork is isolated, placed in a white space, on a pedestal. It is expected to speak for itself, undisturbed by outside noise. This process of sacralisation can be effective in a context where the autonomy of the object is paramount. In design, the dynamic is quite different. Here, meaning resides not only in the object itself, but also in its relationship to the user, situation or environment it was made for. A chair without the possibility of sitting, a textile without the sensation of touch, a tool without the potential for use: we lose content when an object is removed from its surrounding world. When participation is possible, another way of understanding is developed.

As Catherine McDermott argues, design curation has increasingly evolved into a form of mediation. It is an active construction of narratives and contexts in which objects can unfold their full significance.1 Donna Loveday describes design curation as a practice where not only selection, but also positioning, audience participation and interdisciplinary collaboration are decisive.2 This article advocates, in the light of these ideas and a social constructionist view, that design curation is not a reduction of context (as in the fine arts world) but an expansion thereof. It does not strip layers, but a curator rather adds them, and it invites (if possible) interaction to also understand the functionality of a piece. This means the sacralising magic of a white cube is rather hampering than aiding exhibitions that focus on design.

The exhibition Colour. Seeing Beyond Pigment at Z33, House for Contemporary Art, Design and Architecture in Hasselt (Belgium), departs precisely from this premise. It functions in this article as a case study for how context, space and narrative are crucial for making the potential of design visible, even (and perhaps especially) when direct touch is impossible. Seeing Beyond Pigment shows contemporary, yet extremely fragile designs. Making it the ideal metaphor for all design exhibitions working with precious items such as historical or one-off pieces.

The starting point of Seeing Beyond Pigment is new scientific and artistic developments in the application of structural colours. Unlike pigments, these colours emerge from an optical refraction of light due to nanoscale structures in a material. The result is an iridescent hue that shifts depending on the viewing angle and the light. Structural colours occur in nature (e.g. butterfly wings or peacock feathers), but now also form inspiration for the laboratory research of sustainable alternatives to polluting pigments. They prove to be a pioneering contemporary alternative to both chemical pigments and bio-based options like those made out of plants, algae or fungi that are often resource intensive and not that lightfast.

In collaboration with Laboratorium, the biolab of KASK & Conservatorium Ghent, we invited a series of designers and artists to the art centre to work with this technology for the first time. The result is a set of new works that balance tactility and visual seduction. The creations are best viewed from all different angles, to catch all their iridescent beauty. In addition, they call to be touched. Yet that very touch would damage the colour: like the wings of a butterfly in nature, touching structural colours destroys the refracting nanostructures they are made of. This paradox became a curatorial challenge: how can you give an audience a rich, sensory experience (literally from all angles) of a design object when direct interaction is not possible?

The scenography was developed by Woman Cave Collective (Chloé Macary-Carney and Léticia Chanliau). Their design, inspired by archaeological sites, divides the space into raised platforms and walkways. The works can be enjoyed from all angles and are presented like findings: visible, accessible to the eye, yet protected. “We wanted to guide visitors without directing them,” says Macary-Carney.3 “The layout invites movement and viewing from multiple angles, while maintaining a certain distance.” Chanliau adds: “But the scenography also adds [its] own narrative to the show. The audience encounters the works as if they are traces from another time, perhaps from a possible future.” Furthermore, structural colours are precarious. Yet if they are preserved correctly, they can survive forever. This is why they are often found in fossils, telling us about a world of colour that has been. Adding the context of an archeological site augments and stresses this intrinsic meaning of the works.

The exhibition and scenography show how a design curator, as McDermott notes, can take on new roles: as a reporter who explains phenomena, and as an agent of change who addresses societal issues. In Seeing Beyond Pigment, the subject is not only colour as an aesthetic quality, but also colour as an ecological statement, as part of a broader discussion on sustainability, preservation and materiality. For this latter aspect, and to bring the audience as up close to the works as possible, binoculars were offered in the exhibition room. The resulting exhibition resists the isolating logic of the white cube. Instead, it embraces the friction between object and context and even augments the possibilities for social interaction.

Design as Social Mediation

In Social Matter, Social Design, Jan Boelen and Michael Kaethler argue that all design is inherently social.4 Objects are not neutral; they are embedded in networks of production, use, and meaning. For me, to curate design, therefore, is to curate relationships. It means positioning an object in the mesh of human and non-human actors that shape its existence. It is acknowledging that meaning and knowledge are created in a social context, and through human interaction, not in the absence thereof. That is why, as I argued earlier, design curation cannot follow the isolating logic of the white cube. This is where Social Matter, Social Design offers a compelling lens: design objects are never just physical artefacts, they are nodes in a network of social, cultural, and historical relations.

Especially in the chapter Everyday Resilience, Mariangela Beccoi points out that all artefacts are political.5 The chapter advocates the idea that objects enable our actions and reactions. We read how everyday objects like pots, umbrellas and goggles are turned into tools of resistance. This happens because they are part of the social context in which we all reinforce and reconfigure the function and meaning of objects by adapting how they are used.

From this perspective, design rarely gives us final answers. Humans keep adapting items and finding new ways to use the objects around them. For curators, this means exhibitions should acknowledge this flux, rather than cover it up. Objects do not need to appear fixed or finished. They can be presented as part of ongoing processes, where their meaning shifts over time. Audiences on their side are asked to do more than simply look. They may handle things when possible, move around them, or picture how these objects could take on different roles in their own daily lives. Design offers many more opportunities for audience participation than fine arts traditionally does.

In Seeing Beyond Pigment, this theory comes into practice. The works on show are more than formal explorations of a new colour technology. They are also touchpoints in a larger conversation about the environmental consequences of traditional colour production, the potential of nanotechnology, and the way scientific innovation filters into our material culture. The scenography reinforces this complexity. By referencing archaeological digs, Woman Cave Collective situates the works simultaneously in a speculative past and a speculative future. The visitor navigates these layers of time and meaning, never entirely outside the story being told. The added context equals added meaning.

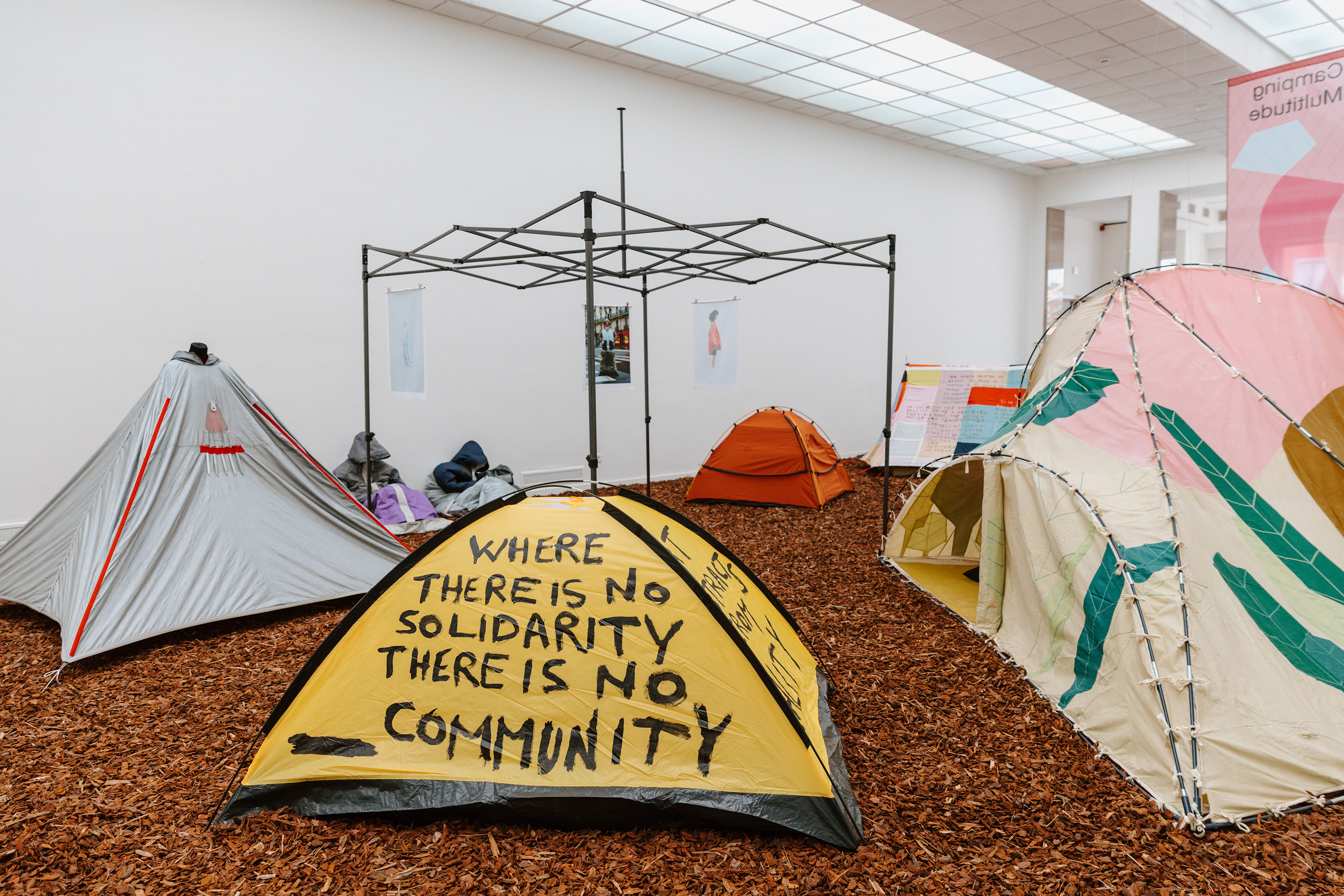

This was exactly also the case in 2022, when I curated another exhibition in the same space – Fitting In, an exhibition focusing on identity and the multiverse. We showcased in the Camping Multitude section eleven different artistic tents all centring on the exhibition’s theme. By adding wood chips to the floor, we created a dusty and (for a museum at least) noisy space. The woodchips turned the space into a true camp site, where tents could be visited and used, and they all started interacting with each other and with the audience. This intervention was very much appreciated by the participating designers, as it added context and elevated the tents from individual objects to a fuller narrative. People started using and appropriating the space and the objects. But it was not understood by the more art-oriented press covering the show, experienced with seeing every object as an artwork in its own sacralised individuality. One reporter critiqued the added context as if the white cube had “to yield to the dogged dictates of accessibility”. It reveals a confusion: what was dismissed as a lowering of standards or a concession to accessibility was in fact a conscious curatorial act of adding narratives. In design curation this is a strength, yet within the white cube tradition such gestures are illegible.

As Loveday notes in her chapter on Curating Narrative and Experiential Exhibitions, design curation thrives when context is layered and when narrative supports the audience’s engagement.6 Objects are a part of a living system, so should be touched and used. Such an approach demands more than simply selecting and displaying works. We need to orchestrate a spatial, sensory, and conceptual framework in which objects can be encountered. In this sense, curating becomes a form of design itself. It becomes a practice of shaping interactions. As design curators, we need to sequence experiences and enable a co-creation of meaning between object and audience. Understanding curation in this way also reframes spaces as something more than neutral containers. It is an actively designed environment, a crafted place to mediate between an object and the meanings it might generate in a social context.

In this sense, design curation operates much like crystallisation in qualitative research as described by L.L. Ellingson.7 The task is not to simplify reality into a linear account, but to create a more nuanced and multifaceted understanding. Like a crystal refracting light in different directions, a well-curated exhibition refracts meaning. By doing so it reveals unexpected facets, angles and resonances. I understand each curatorial decision as a new cut in the crystal, refracting and reflecting the project’s potential meanings. The created complexity does not reduce clarity. It sharpens it. In a social constructionist view, things do not become smaller when examined closely, but bigger. Adding perspectives, contexts and frameworks expands possible meanings and shows what would otherwise remain unseen. What results is not a monological truth, but a field of interpretations that can be co-created by the audience.

This is particularly evident when the work on display is design itself, because the curator is then designing the conditions for one design to be understood through another. It requires understanding design non-hierarchically, and seeing scenography (and graphic design) as an equal artistic practice to the other design fields. The idea of curation as design means for me also accepting that it is iterative, adaptive, and collaborative. Just like other forms of design, it makes use of prototypes (in the form of models or mock-ups), user-testing (observing how people move through and respond to the space), and revisions (adjusting lighting, captions, or sightlines). Curators and designers share in this sense a methodology, even if their final products differ. The exciting thing here is that this means design exhibitions can change their form over the course of time.

Method and process

As the meaning of design (and all art for that matter) is constructed in social relationships, and as stories are conveyed through those same social interactions, bedabbling an exhibition with human interaction is key in crafting it. When starting the curatorial process for Seeing Beyond Pigment, our research therefore began with the tension between the seductive tactility of structural colour and the impossibility of human touch. This limitation was not a constraint to be hidden but a condition to be addressed openly. Rather than compensating with excessive textual explanation or didactic panels, I looked for ways to embed meaning in the spatial experience of the exhibition itself.

The scenographic collaboration with Woman Cave Collective was essential in this regard. Macary-Carney and Chanliau approached the exhibition space as a terrain to be navigated rather than a container to be filled. “The works needed both protection and visibility,” recalls Macary-Carney. “We imagined them as if they were archaeological artefacts. Delicate, irreplaceable, yet still part of a wider landscape.” The raised platforms and narrow walkways became more than pragmatic solutions. They choreographed movement, framing each object as a moment of encounter.

The shifting tones of the structural coloured works are perceived differently depending on light, movement and viewing angle. This perceptual variability became a key curatorial concern. Without touch, how could the audience engage bodily with the works? The scenographic design addressed this question spatially. By elevating the pieces and creating narrow pathways, Woman Cave Collective forced visitors into a choreography of looking. Every step altered the visual impression. “We wanted to make the act of viewing active,” notes Macary-Carney. “The audience is not static; they are co-producing the experience through their own movements.” As Macary-Carney and Chanliau made clear in our conversations, this approach was not about illustrating the works, but about creating a setting in which their multiple meanings could coexist.

Rather than dictating the scenography, I worked with Macary-Carney and Chanliau as co-authors. Their scenography to me was equal to the other more object-related designs presented in the show. Decisions emerged through dialogue, iterative sketches, and adjustments to the physical and conceptual demands of the works. For me, this is exactly what Loveday identifies as a shift to a more interdisciplinary practice.

Reflections: Curating as Context Creation

My experience with Seeing Beyond Pigment confirmed for me once more: design curation is not an adapted form of fine arts curation, but a fundamentally different practice. As design curators, our discipline requires us not only to present, but also to mediate and to contextualise. We have the opportunity to operate in the space between object and audience. In doing so, we have to acknowledge that meaning is not static. It is co-created, shifting with every encounter, every movement through the space. We cannot pretend there is only one way of understanding our present concerns or our speculative futures.

Seeing Beyond Pigment was, in this sense, both a case study and a manifesto. It demonstrated that even when touch is denied, design meaning can still be co-created – through the choreography of space, the layering of narrative, and the deliberate weaving of context into a coherent yet open-ended experience. This is the work of design curation: not to strip away, but to add. Not to isolate, but to connect. And, above all, to recognise that in the interplay between object, context, and audience, new meanings are always waiting to emerge.

References

- Catherine McDermott, ‘New Sites of Practice – educating new curators of the contemporary’, in Defsa 2007: Design Education and Research Conference, Design Education Forum of Southern Africa, pp. 1–6 <www.defsa.org.za> [accessed 18 November 2025].

- Donna Loveday, Curating design: Context, culture and reflective practice, 1980–2020 (Lund Humphries, 2022).

- Chloé Macary-Carney, & Léticia Chanliau, Interview by Annelies Thoelen (Unpublished manuscript, 2024).

- Jan Boelen & Michael Kaethler (Eds.), Social matter, social design: For good or bad, all design is social (Valiz, 2020).

- Mariangela Beccoi, ‘Everyday Resilience, On pots, tear gas and creativity’ in Social matter, social design: For good or bad, all design is social, ed. by Jan Boelen & Michael Kaethler (Valiz, 2020), pp. 99–105.

- Donna Loveday ‘Curating Narrative and Experiential Exhibitions’, in Curating design: Context, culture and reflective practice, 1980–2020, ed. by Donna Loveday (Lund Humphries, 2022).

- Laura L. Ellingson, Engaging crystallization in qualitative research (Thousand Oaks: Sage, 2008).