Published on

30.06.2023

Over the past twenty years David K. Ross has produced installations, photographic and filmic works that focus primarily on the architectural and social compositions of civic and cultural infrastructures. Ross is currently a guest lecturer at the Estonian Academy of the Arts in Tallinn, where he has been teaching in the Master of Contemporary Art, and Architecture and Urban Planning programmes.

1.

At the beginning of the 19th century Luke Howard, a self-trained meteorologist and professional chemist, projected the Linnaean system into the sky. He wanted to classify clouds. Five basic genera form the framework that now comprises close to one hundred named cloud ‘species’. However, unlike plants or animals, clouds are mutable, careening across multiple classifications in minutes. A wolf, or Canis lupus is always a Canis lupus, but a Cumulus humilis might pass into a Cumulus mediocris reforming into a Cumulus congestus before simply dissipating. Howard foregrounded this ever-present problem, acknowledging the fickleness of clouds in the title of his treatise On the Modification of Clouds. The Linnaean system, itself a construct of rationalist thinking, was pressed into service as a cloud identification device which, though reliable to a certain degree, is still a fiction. This is suitable, given that clouds themselves are the repositories and instigators of so many untruths.

2.

Everyone likes clouds, they lift the heart. They lift the eye. Actually, they lift the heart because they lift the eye. Cognitive scientists say that people place gods in the high blue sky because looking up causes a rush of dopamine in the brain. Yet clouds do more than draw your eye upwards; they invent your imagination.

This happens on a small scale when you lie on your back on a hill on a summer day gazing up and say:

“Oh look, that one’s a camel!”

“There’s Werner Herzog!”

“A can opener!”

“The Taj Mahal!”

The interpretation and re-interpretation of shifting shapes of cloud is one of the most basic exercises in free imagining known to you dwellers upon the earth. Also useful for reminding you that most of the ideas you conceive about the world are fragmentary, fugitive, self-ruining and soon forgotten.

— Anne Carson, Lecture on the History of Skywriting

3.

We are encouraged to think of clouds as mutable, without physicality or consequence, as manifestations of imagination and ephemerality. But this too is a fiction. Clouds are things of considerable substance. Imagine the kind of cloud that Anne Carson asks us to conjure: rounded, singular, benevolent, camel-like. This cloud (likely a Cumulus mediocris), placidly floating over your head on a summer day, would weigh about half a million kilograms. If that single cloud were to join other nearby clouds, accumulate extra moisture and energy, and become very large, you would look up to see a Cumulonimbus incus. A summer downpour may follow, with powerful winds and bolts of lightning generating 300 million volts of electricity.

4.

A version of The Cloud touches the ground in Estonia at the Greenergy Data Centre (GDC) in Harku, fifteen kilometres outside Tallinn. The GDC sits on a quiet country road in what was once a farmer’s field. But this building is a long way from being pastoral or genteel. The facility is flanked by one of the largest electrical substations in Estonia, surrounded by three-metre high fencing, and monitored by AI-controlled surveillance cameras and heat sensors 24 hours a day. The GDC is designed to deliver a limitless flow of data in and out of its walls. Data may come and go as it pleases, but don’t try to visit without an appointment and submitting to a mandatory pre-visit ID verification protocol.

GDC’s owners, The Three Seas Initiative Investment Fund is owned and managed by a cluster of former Soviet bloc countries, who came together to build their own data storage centre (amongst other infrastructure projects) to provide secure, environmentally positive data storage and transfer services for their partners and clients. No one at the GDC can or will tell you whose data is stored there.

The amount of electricity the centre uses on a daily basis is equal to that of a small Estonian city like Viljandi. Like all data centres, it survives by making its own weather, using complex liquid cooling systems designed to draw potentially damaging heat away from hard drives and servers, circulate it out of the server rooms, and dissipate it via roof-top chilling units. This need for electricity, and a lot of it, is why the GDC is plugged directly into a substation, and by extension, the Estonian electrical grid. But, as we know, the electrical grid is not, in the Cartesian sense, actually a grid. In the same sense that The Cloud, in the meteorological sense, is not a cloud.

5.

Quiz: Imagine two monumental clouds of gas. One is comprised of the annual CO2 generated globally by the world’s data centres. The second cloud contains the CO2 generated globally by all commercial airline traffic over the same period of time. Which cloud would be bigger?

Uko Urb said to me during a recent tour of the GDC facility, “basically what we do here is convert electricity into heat.” Scratch the surface of any email, text, or social media post and you will find bits and bites, ones and zeros. Scratch further into those binary indicators and you’ll find microwatts. The movement of data requires electricity. And keeping that data in motion creates heat. And heat is dangerous for sensitive electronic equipment. Keeping this equipment cool with massive air conditioning systems requires energy. It’s a big hot loop.

Some data centres offload their excess heat, exergy, as it is known, to adjacent apartment buildings or even to swimming pools. This makes sense, but only to a certain point. Hard drives and servers are designed to store and circulate data, not heat. Can you warm your hands up on the top of your laptop? Yes, but there are better ways to do so, like putting your hands on something actually designed to convert electricity into heat. A radiator.

Answer: Both CO2 clouds are about the same size. Or, to put this another way: one Google search uses about the same amount of electricity as frying an egg, though no one is telling us to look up the difference between an alligator and a crocodile in a hardbound encyclopaedia to save the planet.

6.

If you had an extra thirty minutes and wanted to stretch your legs, it is possible to walk from the Greenergy Data Centre to the Harku Weather Station. Operated by the Estonian Weather Service (Riigi Ilmateenistus), this 18th century institution is separated from the GDC by just three kilometres. And yet it feels like a world away. One place is a metaphor for clouds, the other, a collector of them. Their close proximity and their rustic locations are not entirely coincidental. Both require unobstructed, isolated surroundings to function properly. In the relatively flat plain surrounding the coastal city of Tallinn, the facilities are perched on a rise of land forty metres above sea level. Not exactly the Alps, but high enough to catch unobstructed winds. The GDC uses the breezes to assist with its rooftop cooling units; the weather station makes an account of them, along with precipitation, barometric pressure, and of course, clouds. If you were to climb the tower that supports the rotating radar installation the station uses to ‘see’ the weather, you would easily spot the Greenergy Data Centre. The Harku Weather Station building pre-dates the GDC’s arrival by about thirty years. Was it a premonition?

7.

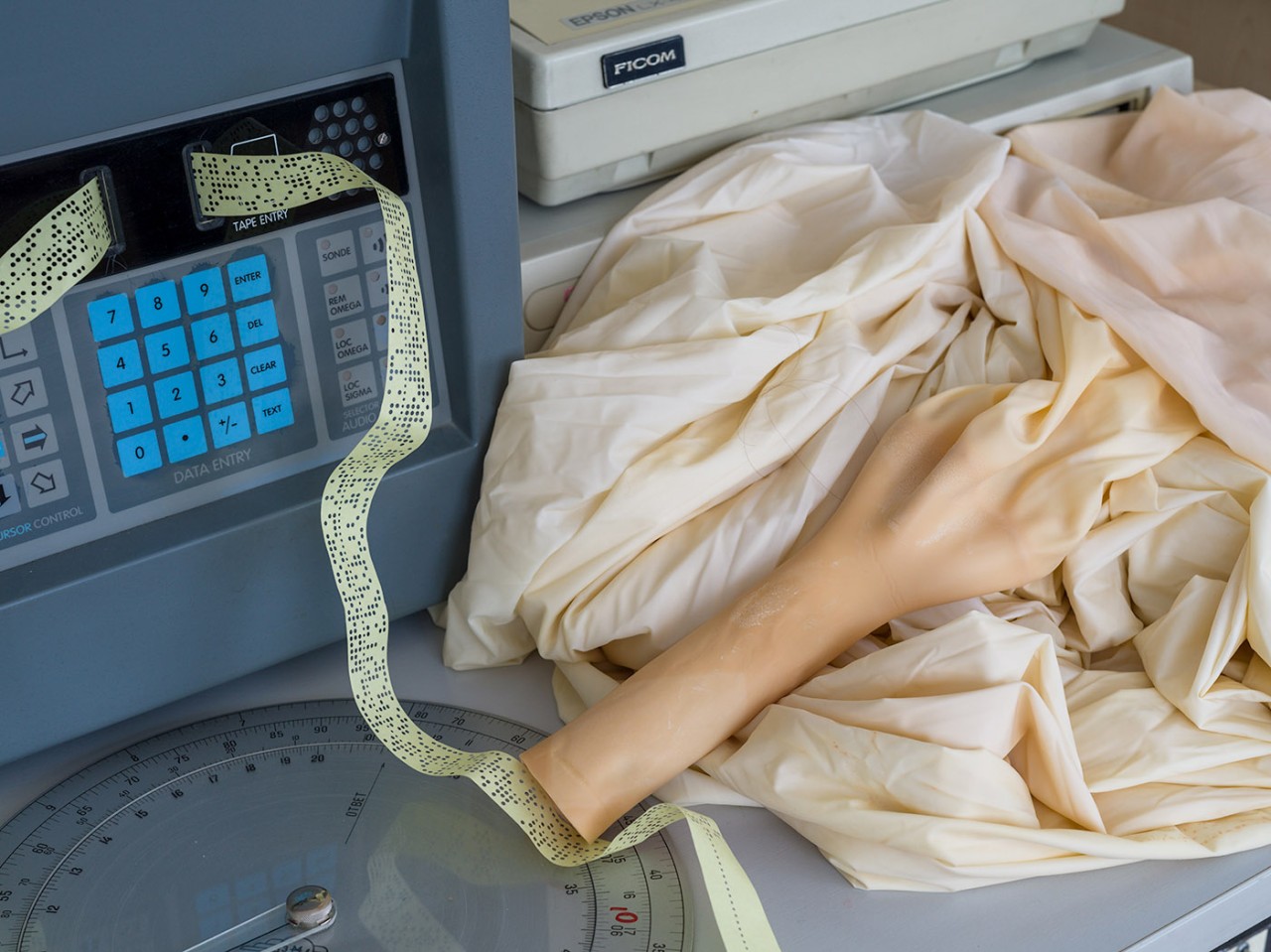

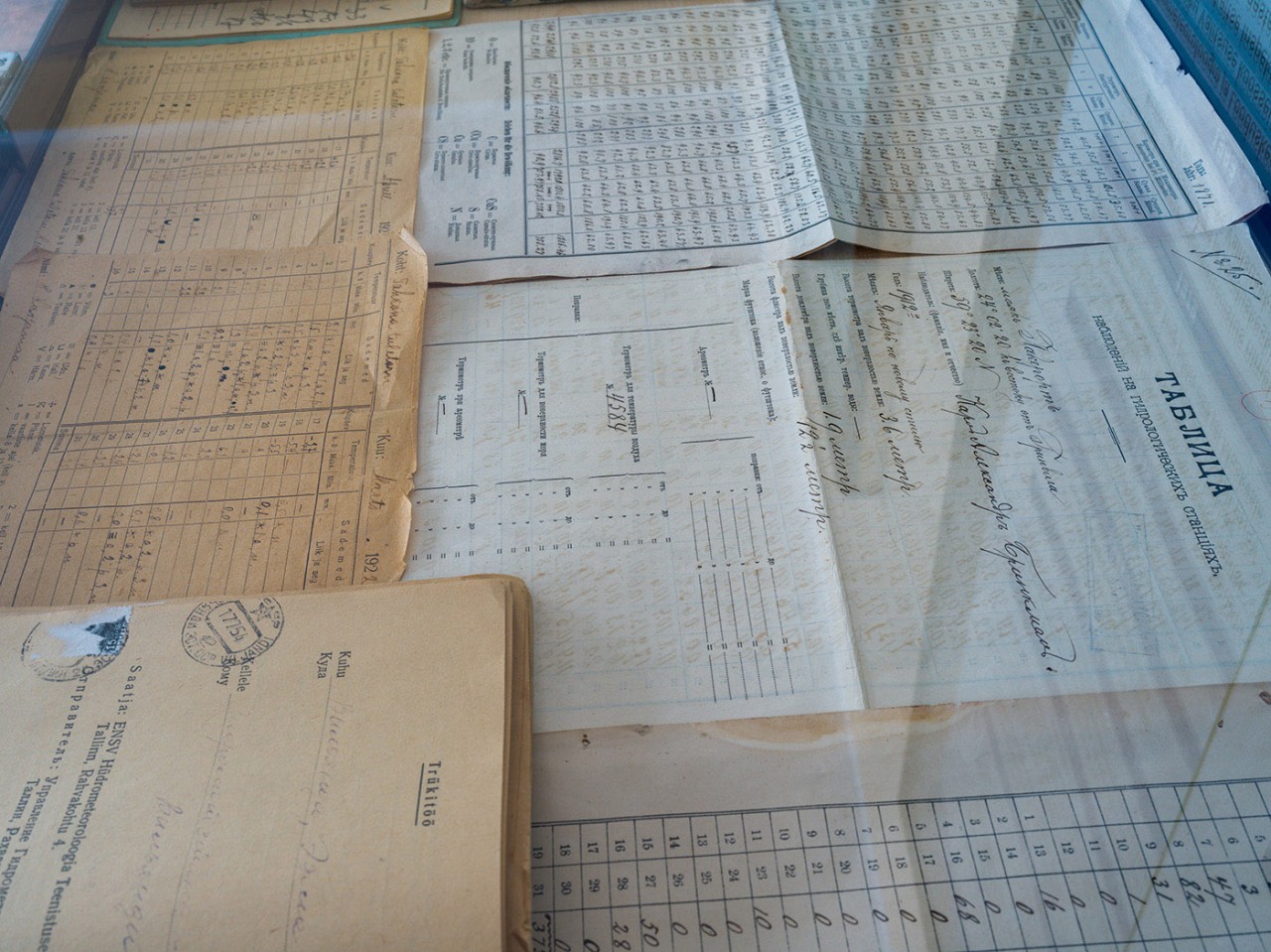

The Harku Weather Station is also a working museum of sorts. Almost all data collected by the centre is now achieved with automated equipment and remote sensors. Like the GDC, the weather station is designed to both acquire and disperse data. A powerful laser shoots straight up into the sky precisely measuring as many as three separate cloud heights and their densities. An automated system selects, fills, and releases one gas-filled weather balloon fitted with an electronic monitor every day at 2:30am. But a surprising amount of analog equipment is still maintained. “If the electricity goes out we need a backup method for collecting weather data,” Miina Krabbi, the Head of Meteorological Observation Department and tour guide, told me.

Inside the station are two museum rooms filled with equipment too old to be pressed into service in the event of a blackout. There are cabinets filled with tools and devices that once had a purpose, though still have substance. They have the simple elegance of analog cameras or farming tools from the 19th century. One can easily surmise their function just by looking at them. Metaphors are not required.

8.

The weather centre is manned – or rather womanned – 24 hours a day. Its staff is all female and, according to the archival photos mounted along the building’s main hallway, it has been a gyno-positive space for a very long time. The photographs show women from the last fifty years using the same tools which are stored in the adjacent display rooms. Every day and every night that the centre has functioned over the decades, these women have collected data. Wind speed, precipitation, barometric pressure, temperature, cloud cover. Repeat.

Tucked away in one corner of the weather centre there is a room with a wardrobe, a small table, a bed, and an alarm clock. Despite advances in automation, every three hours, day and night, the woman on duty is required to walk outside, look up, and take note of the clouds overhead. No automated system yet exists that can look up and say: “that is Stratus nebulosus opacus.”

9.

Question: Is ultraviolet light stronger on sunny days or cloudy days?

Everything is filtered now. Algorithms sieve desire. Suggested playlists, recommended readings, “people who bought,” and ads for the thing you just searched for: all routine. The difference between desire and need is becoming increasingly foggy. We should not be surprised that clouds are synonymous with aspiration and bewilderment.

Answer: Cloudy. Ultraviolet light is amplified by clouds, bouncing around inside them, then escaping, then hitting the ground, then bouncing back up, more amplification, then blasting down to the ground again, stronger still.

10.

Quiz: Which best describes you:

a) My head is in the clouds.

b) My head is in The cloud.

c) All of the above.