Published on 14.06.2024

Robert Rosenberger is President of the Society for Philosophy and Technology and an associate professor of philosophy in the School of Public Policy at the Georgia Institute of Technology. As one of the central developers of the postphenomenological school of thought, he studies human interactions with technology, including deep dives into topics such as imaging technologies, driver distraction, phantom vibrations, and the critique of anti-homeless design. His edited or co-edited collections include Postphenomenological Investigations, Postphenomenology and Imaging, Philosophy of Science: 5 Questions, and The Critical Ihde. His monographs include Callous Objects: Designs Against the Homeless, and Distracted: A Philosophy of Cars and Phones. rosenberger.spp.gatech.edu

Ave Mets is a research fellow of philosophy of science at the University of Tartu. She did her BA, MA and PhD under the supervision of the grand old man of Estonian philosophy of science, Rein Vihalemm, and continues his practice-based style of conceptualising science. She studies philosophy and the history of technology and science (especially chemistry), measurement, and scientific and alternative (especially indigenous) world pictures. She has spent considerable periods of her academic life at the RWTH Aachen as junior research fellow, Belarus State University as post-doctoral fellow, and Washington State University as Fulbright Visiting Fellow, and taught courses at several universities in Europe and elsewhere as a guest teacher.

In September 2023, Robert Rosenberger, one of today’s leading philosophers of technology, was invited to Estonia to give an intensive workshop “Postphenomenology, technoscience and hermeneutics”1, organised by the Chair of Philosophy of Science of the University of Tartu. The visit also included three public lectures which are available online.2 In this interview with Ave Mets, Rosenberger introduces the possibilities for using ideas from postphenomenology, the school of thought in the philosophy of technology founded by Don Ihde, in the analysis of our technology-based contemporary societies. The interview takes a closer look at human-technology interrelations – how technology mediates the world to us, how it enables, enhances and disables certain features and sets us on certain paths of social and technological development.

Ave Mets: You see yourself as doing philosophy of technology. Do you think your brand of philosophy can also be seen as social philosophy? Can one do philosophy of technology without consideration of social aspects?

Robert Rosenberger: Technology is social. Most of the technologies we use in a day were designed and made by other people. Much of our usage of technology has effects on others. And much of our lives involve the navigation of the effects of others’ technology usage. So, in the field of the philosophy of technology – my field, a field of thought that tries to wrap its head around the ethical, political, and various other dimensions of technology – social issues are necessarily central. This is why there is so much overlap between work in the philosophy of technology and work on the philosophy of language, social epistemology, science and technology studies (with their anthropological and sociological investigations of technology), and related areas of inquiry.

Nevertheless, not all work in the philosophy of technology necessarily begins with the social dimensions of technology as its jumping off point. That is, part of what we are doing here is grappling with the complexity of technology. So, any given philosophical investigation may begin with any specific aspect of this complex topic, such as the exploration of ethics, or metaphysics, or a person’s individual experience, or whatever. But it does seem that in any case, the study of the philosophy of technology must build up to an account of the sociality of technology.

We can note too that philosophical investigations into technology do not necessarily have social issues as their end point either. That is, work in the philosophy of technology may also build further from the topic of the social dynamics of technology to explore, say, larger economic or political structures, or may even consider technology’s impact on a global scale, such as in the case of climate catastrophe.

For example, my own work in the philosophy of technology is based on a perspective called postphenomenology. Don’t let that long and strange word intimidate you. This is the name for a useful and quite interdisciplinary school of thought, one that attempts to build a practical toolkit of concepts for describing people’s experiences with technology. These ideas help to articulate how technology usage shapes people’s experiences, choices, identities, and ethical situations. They’ve been taken up in the study of everything from technologies of the classroom, the laboratory, the roadway, public space, the household, and many of the other arenas of everyday life.

The postphenomenological school of thought builds centrally on the work of the American philosopher, Don Ihde, who actually passed away just after his 90th birthday earlier this year, a fact that I have not yet fully come to terms with. He often referred to his philosophy as the study of “human-technology relations,” and he explored how technology usage transforms human experience. In this language, technologies mediate human relationships with the world, and these technological mediations are never neutral, always involving complex transformations and trade-offs. The title above, stating that “technologies are non-neutral,” is a quote from Ihde’s 1990 masterwork, Technology and the Lifeworld3. But it’s a sentiment shared by many philosophers of technology. And it is a live and contemporary topic among both postphenomenologists and their critics to figure out how best to expand these insights about individual human-technology relationships into larger accounts of the social situation of technology.

AM: Do you think artists, designers and engineers merely materialise the predominant ideas and attitudes current in a society? Or do you think they can also create ideas and attitudes? What is their (moral) responsibility in this?

RR: Ihde has usefully identified a kind of mistake that he sees people often making in their thinking about technology, something he calls the designer fallacy. An influential notion within studies of literature is what’s called the intentional fallacy, which refers to the mistaken assumption that what an artist’s work really means is whatever that artist had intended. This is a mistake, so the argument goes, because once it is out of their hands, a work of art (such as a book) can be meaningful in many different ways to the many people that interpret it in their own ways. Ihde argues that the same is true for technology. The meanings and the effects and the future versions of a device do not reduce to what its designer had in mind for it. In Ihde’s terminology, technologies are instead multistable. After they leave the hands of their designer, a technology can go on to be used for multiple purposes, or can mean different things to different users, or can be developed further along many different trajectories.

What does this all mean? According to Ihde, it means two seemingly contradictory things at once. On the one hand, it means that predicting how a technology will develop, and how it will have effects on the world, is exceedingly difficult. And yet on the other hand, it also means that we have an obligation to do our best anyway – as designers, as artists, and thinkers about technology – to predict how devices will affect people. To do so, we must keep close to a conception of technology as non-neutral, and not fall into the trap of assuming that technologies will necessarily lead in utopian or dystopian directions.

Accordingly, Ihde has long observed that philosophical analysis tends to happen after the technology has been made and it is out there in the world, and he’s argued that more should be done to get philosophical reflection – and especially ethical analysis – into the research and design (R&D) process itself. Through the work of Peter-Paul Verbeek and others, these insights have been developed into a full blown postphenomenological account of ethics in design, sometimes called technological mediation theory. As Verbeek puts it:

The Design of technologies is a highly responsible activity. Designing technology is designing humanity, in a sense. Any technology will help to shape human actions and experiences, and will therefore have an impact that can be understood in ethical terms. Designers materialize morality.4

Thus, it is imperative to draw out and understand how and where ethics takes place throughout the process of design, implementation, and usage.

This can help to more fully consider what it means to understand technological non-neutrality. Under this conception, it is not merely the case that technologies have both good and bad effects, although they do. It is that technology usage actively reshapes the world, and in the process it reshapes the users themselves. As Olya Kudina puts it:

Technology enables different or new perceptions that join our bodily and cultural awareness to form a basis for further interpretive processes. For this reason a person is not the same person and the world is not the same world when they find themselves in a technologically mediated situation.5

Technologies are thus non-neutral mediators of human experience not merely in that they enable new actions and perceptions and decisions; technology usage also co-constitutes who we are as actors, perceivers, and decision-makers, and at the same time also co-constitutes the world that is encountered and perceived, as well as the decision-making context.

To consider an example out of my own work, we can look to the topic of smartphones and driver distraction. In my book, Distracted: A Philosophy of Cars and Phones6, which comes out later in 2024, I explore in detail the scientific research which shows people to be bad drivers when they talk on the phone. One of the central findings of the cognitive science research literature is something that some people find surprising and inconvenient: both handheld and hands-free phone conversations are associated with a dangerous drop in driving performance. It is true that handheld texting while driving is found to be the most dangerous phone-related activity; it is of course distracting to look away from the road to read your phone’s screen. However, the findings are clear that conversation over the phone – including a hands-free phone, such as using a speakerphone or headset – is also dangerously distracting. This means that you can be dangerously distracted by the phone even if your hands are on the wheel and your eyes are on the road. After reviewing the stacks of empirical research on this topic, I spend most of Distraction attempting to develop theoretical accounts of how this kind of driving impairment is possible, building on both cognitive science and postphenomenology.

This also leads to a kind of practical critique of the design of contemporary cars. Building on the account of technological mediation developed by Verbeek, Kudina, and others, we can draw out the ways that the technologies of the car – and especially its dashboard – co-constitute driving as a specific kind of activity. I argue that contemporary dashboard infotainment systems (i.e., complex touchscreen displays that pair with smartphones to offer a variety of computing and communications functionalities) are non-neutral. They can be understood to anticipate a certain kind of driver, one that will be doing more things than only focusing on the driving task. Yes, one can and should decide to forego using the dashboard and phone for communicating with others outside the car while driving. But our cars are now designed with an expectation that drivers will engage in hands-free communications. And I’m trying to raise awareness of these dangers.

AM: Does nature in a philosophy-of-nature sense in any way fit into your philosophical approach? How do care and concern for other beings and nature (our home planet) influence and get influenced by technology? Can postphenomenology account for our responsibility for the environment, e.g. sustainable production?

RR: One of the key philosophical commitments of postphenomenology is the combination of insights from the phenomenological and American pragmatist traditions of philosophy. I take it to follow from these commitments that there is not a kind of essential distinction between the natural and the technological, or the natural and the societal. This is in tune with the kinds of claims made by the philosopher Donna Haraway, who often argues that nature and culture must be understood as essentially intertwined, emerging in relation to one another. She writes, “Subjects, objects, kinds, races, species, genres, and genders are products of their relating”7. In our contemporary world – one of globalisation, modern industrialisation, or the Anthropocene as some put it – nothing can be understood as merely natural anymore. And it seems that when we do encounter things out in the natural environment, they have the potential to be technological things if put to our own uses. For example, in my view a stick or branch from a tree becomes a technology the moment we use it for some human purpose; for example, as a lever, or a club, or a piece of found art. To take an example from the philosopher Albert Borgmann, when someone takes a jog in a park, this may on the one hand be understood as an encounter with nature, but on the other must also be understood in terms of the human designs on that park, that sequestered and manicured and maintained section of earth that is in its own way a kind of technology. In many parts of the world, the natural environment has been largely colonised by humanity, and what little wild nature that remains serves as a kind of border case. Writing back in 1984, Borgmann argues: “Thus respect for the wilderness will never again be nourished by its formerly indominable wildness. On the contrary. The wilderness now touches us deeply in being so fragile and vulnerable.”8

Of course we are faced with a generational challenge in the problem of how to address global warming. Many in my field of the philosophy of technology are flailing around for ways to think about these dangers and how they may be addressed. Postphenomenology, meanwhile, with its jumping off point of human-technology relations, is not especially well situated to immediately make contributions to this issue; it is not already an environmental philosophy. Critics are quick to point out that if one focuses mainly on individual human experiences, then it may be difficult to grasp Earth-wide problems, like global warming. I do agree that there is work to do to better connect postphenomenological insights to larger accounts of the political and social world. But even in the face of these limitations, on the issue of climate change, there are useful postphenomenological contributions being made.

It seems to me that one way that postphenomenology may be able to make a distinctive contribution to thinking on the environmental catastrophe would be to help to develop ways to break these issues into the everyday lives of technology users. One specialisation of the postphenomenological perspective is issues of human perception, and in particular the embodied and habitual aspects of human perception. One important element of the climate crisis, as I see it, is that despite its importance it does not always enter the everyday normal experiences of many people. For some people the problem can be easy to ignore, easy to dismiss as remote, easy to underestimate. It may be possible to work with activists trying to raise awareness of these issues to help develop ways to pierce the realm of people’s normal lives.

For example, one of my favourite inventions on this theme is the “SinkPositive” or the “Sink Twice,” a sink-like interface that mounts upon the tank of your toilet. With each flush, the clean water that fills the tank for the next flush comes up and out into the sink feature so that you can use it to wash your hands before it drains down into the tank. So, it’s a nice way to save water – using the water for the next flush to wash your hands. However, the interesting phenomenological moment comes when you are finished washing your hands and the water keeps flowing and flowing and flowing, continuing to fill up the tank. As you stand there with the water continuously flowing, it can be quite striking and instructional to see just how much water is used for each flush. A feature of the toilet that is usually hidden inside this device – namely, just how much water it is using – is now there for you to experience.

I would be interested to see more examples of this kind gathered, and to do some postphenomenologically-informed philosophical reflections on how best to insert these kinds of insights into our daily effects on the planet. Then, importantly, we would need to find ways to link these personal effects to the larger effects perpetuated by the larger-scale institutions (e.g., industries) upon the world around us.

AM: How can the philosophy of technology contribute to a more equal and humane society? To what extent does care depend on technology? How much do we rely on technology in tending for the beings to be cared for and looked after?

RR: Care is an under-theorised notion within philosophy, best brought to prominence perhaps only in recent decades by the feminist care ethicists. And the philosophy of technology has been slow to integrate these insights, although some new work has been making some important connections. I’ve also always thought that there were connections just waiting to be drawn between the postphenomenological perspective and issues of care, especially in an ethically and politically activist sense. Even in the short review of postphenomenological themes here, we can see links to issues of care in the emphases on the inextricable relationality between entities, the integral focus on practical issues of concern, and the ethical responsibility that is a part of art and design. Pulling these together, there is room for the development of themes of care within postphenomenology specifically, and the philosophy of technology more generally.

In a postphenomenological spirit, it can be helpful to follow these implications through the details of a practical case. Let’s turn to my own work on the politics of the design of public spaces. I have been criticising the way that the objects of public spaces are often designed to discriminate against the poor and homeless. One way to consider the issues of technology and the notion of care is to reflect upon the converse of this idea: the notion of hostility. The topic of what is sometimes called hostile architecture or hostile design has been a tool for the criticism of public-space design in discussions within social media and online journalism for some time, and has been recently receiving attention from academic researchers. One paradigmatic example is the design of benches, such as those located in parks or subway platforms. Sometimes people who are living unhoused will use public-space benches as a place to sleep. In terms of the postphenomenological framework, we can think about this in terms of the notion of multistability. A bench is multistable, usable for multiple purposes, including both its normal designed purpose as a place to sit, but also for the alternative purpose as a kind of improvised bed. The hostility comes in when we see examples of benches set with armrests or seat dividers that function to close off the bench-as-bed stability – the possibility of using the bench as a place to lie down. Here we see a pervasive and everyday example of the politics of design, with implications for ethics and issues of care, framed in a language of postphenomenological multistability.

And we can see these kinds of things everywhere. For example, while travelling through Tallinn, I noticed this kind of garbage can design (see Figure 1).

I am no expert on how the poor and unhoused are treated in Estonia. But this kind of garbage can design is interesting to me because it serves multiple purposes at once. Not only are these devices receptacles for trash. But public space garbage cans in many cities around the world serve an alternative usage: a source of discarded food, or recyclable materials that can be traded for money. A can like this one with a small opening can deter people looking to reach in and take things out from inside. The locking mechanism that is built into the housing further protects the garbage inside from access by unauthorised people.

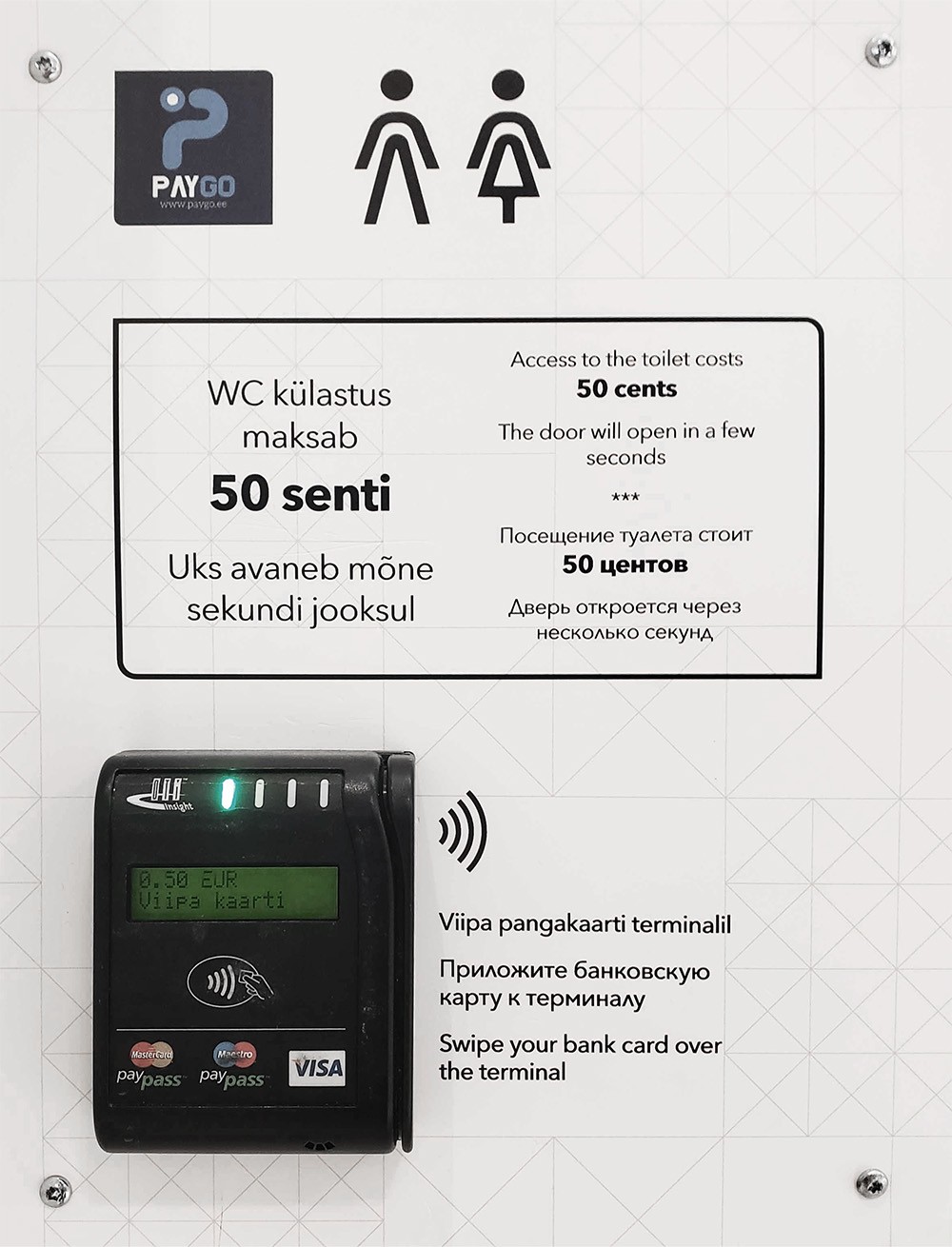

Or take for example this setup (see Figure 2), which requires payment for access to a restroom in a Tallinn shopping mall.

Another typical example of hostile design is the restriction of access to particular amenities by adding a monetary charge like we see here, or even by simply removing these amenities altogether. Restrooms are a good example. Some cities will not feature any restrooms at all across large areas, except for those within exclusive spaces such as private office buildings or restaurants restricted to paying customers.

My argument is that these kinds of hostile designs, when taken together with other institutions that also target the unhoused (such as anti-homeless laws), can have the effect of pushing vulnerable people out of shared public spaces. We see in these kinds of examples that technologies are shot through with issues of power. Another part of what it means for technologies to be non-neutral is that they may issue advantages to the already privileged, and may further disadvantage the already vulnerable. They also have the potential to challenge these already set political arrangements.

What’s more, we as users can become implicated in these political dynamics. Again the examples from the public space are useful. For many of us who are neither poor nor unhoused, in our everyday lives we may fail to notice the political dynamics built into the world around us – the locked garbage cans, the anti-homeless laws, the restrooms only available to paying customers, etc. In this way, our own privileges are reflected in our perceptions, and can become over time set within our normal and habitual relationships to the world. Our own sense of normalcy itself can become implicated within the ethical and political dynamics around us.

With these kinds of thoughts, we can begin to bring some of these insights into issues of care and technology that could be developed through the postphenomenological perspective. We’ll need to contend with the complexities of technological mediation, and the obligations of designers and artists who create the world around us and shape how we live within it. And we’ll need to contend with the politics of design, not only in our obligations to care, but in our criticisms of those who discriminate against and take advantage of others.

References

- <https://filsem.ut.ee/en/node/152561> [accessed 23 February 2024]

- The videorecording of the lectures can be found here: “The Philosophy of User Interface: On Smartphones and Driver Distraction” <https://uttv.ee/naita?id=34766>; “Philosophy of Technology and the Control of Public Space” <https://uttv.ee/naita?id=34767>; “How Scientists “Read Images”: The Technological Mediation of the Mars Global Surveyor” <https://uttv.ee/naita?id=34768> [accessed 23 February 2024]

- Don Ihde, Technology and the Lifeworld (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1990), p. 144.

- Peter-Paul Verbeek ‘Beyond Interaction: A Short Introduction to Mediation Theory’, Interactions, May–June, 2015, pp. 30–31.

- Olya Kudina, Moral Hermeneutics and Technology: Making Moral Sense Through Human-Technology-World Relations (Lanham: Lexington Books, 2024), p. 112.

- Robert Rosenberger, Distracted: A Philosophy of Cars and Phones (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2024).

- Donna Haraway, The Companion Species Manifesto (Chicago: Prickly Paradigm Press, 2003), p. 7.

- Albert Borgmann, Technology and the Character of Contemporary Life (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1986), p. 194.