Published on 14.06.2024

Hsuan-Hsiu Hung is a dance and movement artist, whose creative practice weaves together somatics, visual art, dance, and contemplative practices. Her work explores the unfolding experience of self in relation to others through somatic movements in performative, therapeutic, and research contexts. Currently, she facilitates regular Qi Gong lessons and contemplative movement practices that support sustainable self-care in everyday life. dancinginart.com

Kristi Kuusk is a designer-researcher working in the direction of crafting sustainable smart textile services. She explores new ways for textiles and fashion to be more sustainable through the implementation of technology. Kuusk currently works as a research fellow in textile futures at the Estonian Academy of Arts running the Sensorial Design research group. kristikuusk.com

Moving Awareables searches for embodied care through designing somatic interactions with multi-sensorial artefacts. Moving suggests the body setting artefacts in motion, it also refers to the body moving while interacting with artefacts. Awareables plays with the sound of “wearable” and points to something that makes us able to become aware of our own experiences1. In the process of design research, we asked the question of how to bring self-awareness and care through touch to material forms. We responded to the physical and mental tensions that arose from living fast-paced lives, without having many moments to stop and reflect, while witnessing isolation as never seen before (Covid measures), wars as we thought would not appear again, and crimes against humanity that make us doubt the direction we are headed. We contemplated how to offer embodied care to people facing these challenges.

The project kept a continuous loop of embodied practice, design and reflection between a movement artist and a designer-researcher. The transdisciplinary research built on practices and knowledge of embodiment2 by inviting awareness of oneself through touch. It engaged with Soma design where designers examine and improve on connections between sensation, feeling, emotion, subjective understanding and values3, and rely greatly on first-person experiences for design and research4.

Through embodied design ideation, which are practices that work with relationships between body, material and context to enliven design and research potential5, we developed three iterations of soft close-to-body artefacts while exploring the following topics:

Touch between the body and materials

Throughout the project, touch was the main tool for embodied research into oneself and the materials we worked with (Figure 1). Juhan6 describes the experience of touch “Every time that I touch something, I am aware of the part of me that is touching as I am of the thing I touched.” He further explains “we can never touch just one thing; we always touch two in the same instant, an object and ourselves.” Touch allows us to access subjective experiences by bringing attention not only to the physical sensations in the body but also awareness of inner intangible worlds (thoughts, feelings, emotions, memories, imaginations) that unfold through physical interactions.

Designing artefacts that invite embodied awareness

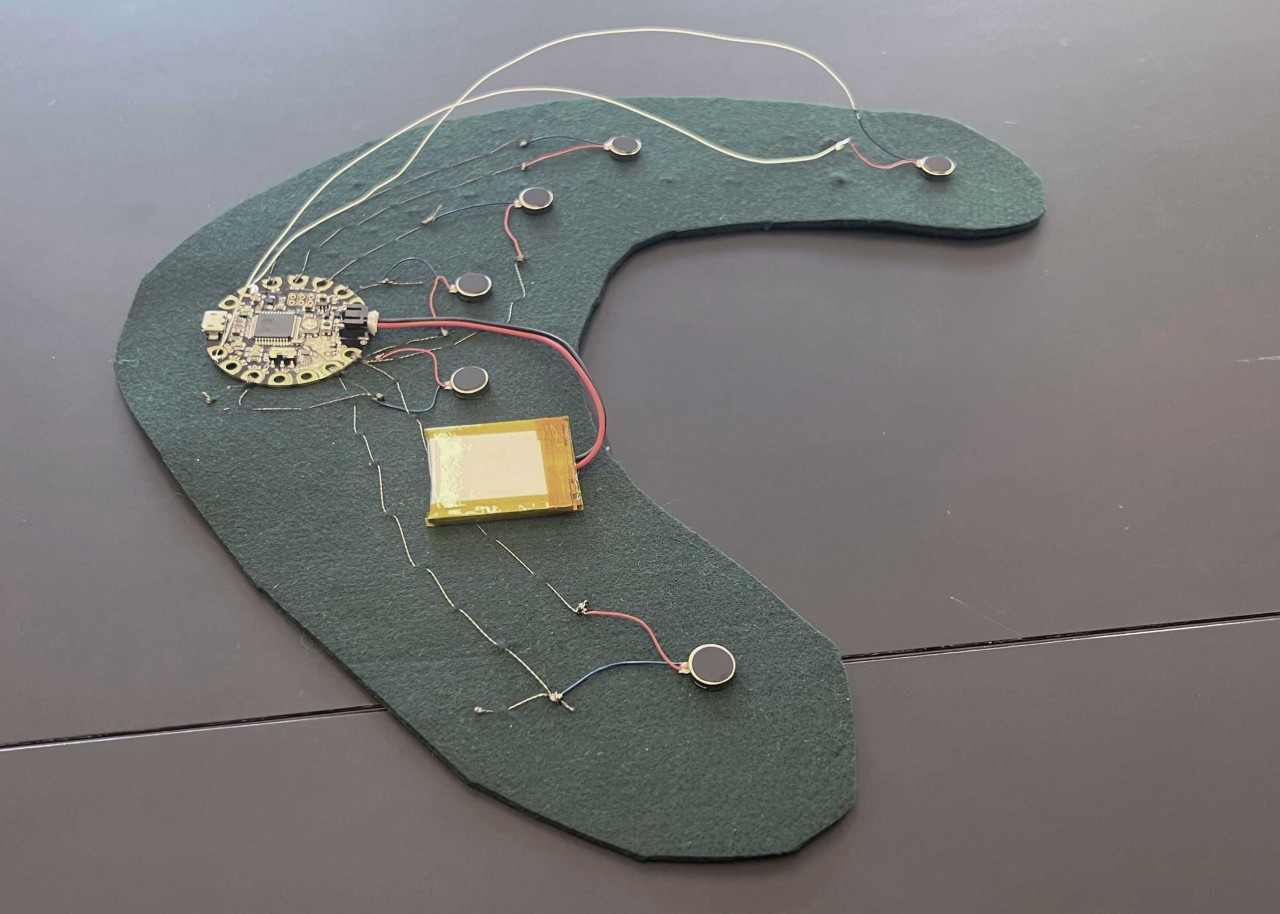

The movement artist initially explored touch with everyday objects to feel her body as well as the somatic responses when meeting the materials. For the first design iteration, we explored the touch sensations of the hands, various textile materials and small vibrating motors. We created a wearable form embedded with 12 vibrating motors (correlating to 12 acupoints on the body) on the felt surface (Figure 2.1). It wraps around the upper back and shoulder area to bring sensations that invite relaxation. The second iteration focused on bringing the sensations even closer to the wearer’s body by attaching the felt surface to an elastic textile which wraps tightly around the upper body. A set of soft textile tubes filled with cotton was added externally for the wearer to lean against to increase the sensation of vibration (Figure 2.2). However, while the vibrating sensations were enhanced, the elastic wearable form inhibited the wearer’s freedom of movement. This led to the third design iteration to create a set of soft tubes with various textile surfaces and fillings (Figure 2.3). Half of the tubes became interactive beyond the movement and textile properties by having electronic components, such as tilt-sensors and vibration motors embedded inside. They widened the scope of reactions we could play with for sensing and actuating in order to bring attention to the (specific part of the) body. The material characteristics of the Awareables invite the wearer to touch, bend, wrap, shake, hold and squeeze the Awareables, making exploratory movements that expand their kinesthetic awareness to enhance the experience of the self7.

Contemplative movement practices informing the design

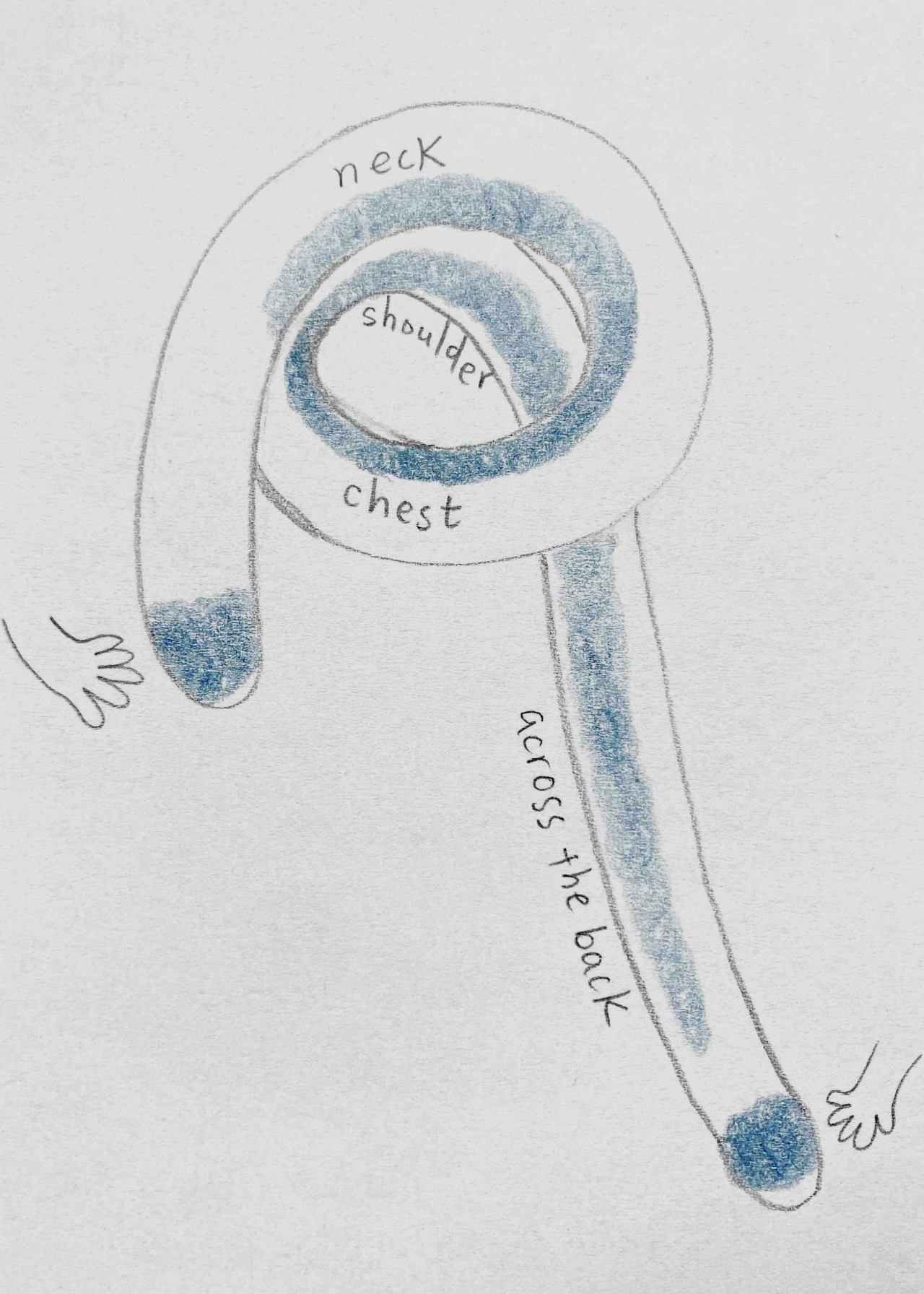

To understand more deeply how the artefacts function, the movement artist developed specific embodied practices that allowed her to track her somatic experience8 (Figure 3). After the interactions, the movement artist took time to reflect and document the experience through drawing portraits of the Awareables (Figure 4). The contemplative documenting process enabled a deepening of the experience, it also made it possible to transfer the embodied knowledge to the designer-researcher in order to feed the knowledge back into the design.

Figure 4. Portraits of the Awareables that document the positions of the artefacts (pencil line), the contact areas with the movement artist’s body (in blue), and the vibrating sensations (in red). The drawings are accompanied by a short journal that describes the artist’s mental and emotional experiences. Drawings: Hsuan-Hsiu Hung

Figure 3. The movement artist explores the artefacts in everyday life settings to track the relationships between the needs of her body, the positions of the artefacts and the resulting somatic experiences. Photos: Mikk Tamme

In addition to the movement artist’s first-person experiences, guest participants were invited to experience the artefacts at different stages of the research. Their interactions with the Awareables ranged from free play and exploration to fully guided sessions, including the final participatory sharing event (Figure 5). Their embodied experiences co-shaped the design of the artefact during the research process.

Moving and being moved by the Awareables

While the artefacts emerged from the somatic movement research, the design outcome also invites somatic experiences. Touch with the artefacts brings attention to the place of contact for the wearer to sense and feel the textures and the buzzing sensations on the body. The embodied awareness creates short moments of pause inviting the attention to notice what is happening with the body now. Moreover, it brings awareness to the more intangible feelings and emotions that emerge from the contact. From the experience of the movement artist and later the invited participants, the gentle contacts with the materials often provoke feelings of care. The material characteristics of the Awareables (soft, smooth, warm, fluffy, etc) invite physical relaxation, which occurs through micro movements in the body. These micro movements come as intuitive responses, such as reflexes, sometimes leading to impulses to move, stretch, or go into specific movements or postures that offer comfort. From this perspective, the body is not only moving but also being moved by the Awareables (Figure 6).

Figure 6. The four images above demonstrate that by attending to the somatic touch experiences, the movement artist follows her impulses to move and to be moved by the Awareables. Photos: Mari Rostfeldt

Through the research, we understood that the somatic effect of embodied awareness is care. The awareness of touch brings caring attention to how one feels in their own body while meeting the material world. We explored designing for those caring attentions through designing the Awareables – a co-designing process that relied on the designer-researcher, the movement artist, and the affordance of our situations (in terms of materials and technologies). Once the Awareables were made, the embodied caring experiences depended on various factors:

1) The material characteristics of the artefacts

2) The different ways people interacted with them

3) How the movement artist facilitated the session

4) The time and space in which the experience took place

5) Personal histories of embodied experience which shaped the current one with the Awareables

6) People’s perception of their own experience

Through embodied explorations with the Awareables, we began to shift our perception of the Awareables from objects to subjects because of their material agencies and what they could potentially do to us9. We began to consider them as other non-human bodies that actively co-designed the experiences with us.

When sharing the project through a participatory event, we noticed both the human and non-human bodies were each relating to, responding to, and influencing each other. Each person formed a unique relationship with their chosen Awareable. Some even said they did not want to be separated from them because of the closeness they had developed together. The Awareables invited caring attention towards the way we interact with materials, and even more, the awareness of how we ourselves are cared for in this meeting between the self and the artefacts. Through the event, we opened up intimate spaces of care between individuals and artefacts, we also witnessed a collective caring space co-created by every body through the event.

At this point in the research, we continue to learn about how somatic interactions with soft close-to-body artefacts could transform our relationships to the self and others. We also look for other possible material forms that the Awareables could use to take shape. Furthermore, we reflect on how we can continue to facilitate such co-created embodied caring spaces and experiences. Among the feedback from the participants, some imagined having the Awareables (and participatory events) regularly in everyday life settings, where people could take time to care for themselves. Some suggested possible materials (that are easy to clean), spaces (office/school/library), and target groups (young children/the elderly/teenagers) based on personal wishes and professional expertise. Together with the participants, we co-envisioned how care could be embodied in society through different people and their ways of moving with Awareables. In practice, it is with our own moving, sensing and feeling bodies that we touch and share this caring experience with whoever (and whatever) we meet in the world.

The project was partially funded by the Cultural and Creative Research Support Measure of the Estonian Ministry of Culture.

References

- Merleau-Ponty, M., Phenomenology of perception (This ed. 1. publ. in paperback) (Routledge, 2014).

- Cohen, B. B., Nelson, L., & Smith, N. S., Sensing, feeling, and action: The experiential anatomy of body-mind centering® (Third edition) (Contact Editions, 2012).

- Höök, K., Designing with the body: Somaesthetic interaction design (The MIT Press, 2018).

- Tomico, O., Winthagen, V. O., & Van Heist, M. M. G., ‘Designing for, with or within: 1st, 2nd and 3rd person points of view on designing for systems,’ Proceedings of the 7th Nordic Conference on Human-Computer Interaction: Making Sense Through Design (2012), pp. 180–188. <https://doi.org/10.1145/2399016.2399045>

- Wilde, D., Vallgårda, A., & Tomico, O., ‘Embodied Design Ideation Methods: Analysing the Power of Estrangement,’ Proceedings of the 2017 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (2017), pp. 5158–5170. <https://doi.org/10.1145/3025453.3025873>

- Juhan, D., Job’s body: A handbook for bodywork (3rd ed) (Barrytown/Station Hill 2003).

- Sheets-Johnstone, M., ‘Kinesthetic experience: Understanding movement inside and out’, Body, Movement and Dance in Psychotherapy, 5(2) (2010), pp. 111–127. <https://doi.org/10.1080/17432979.2010.496221>

- Adler, J., Intimacy in emptiness: An evolution of embodied consciousness (Inner Traditions, 2022).

- Abram, D., The spell of the sensuous: Perception and language in a more-than-human world (Pantheon books, 1996).