Published on

25.11.22

Britta Benno is a drawing and printmaking artist living in Tallinn. Benno is constantly extending the fields and combining conventional media with innovative unexpected layers.

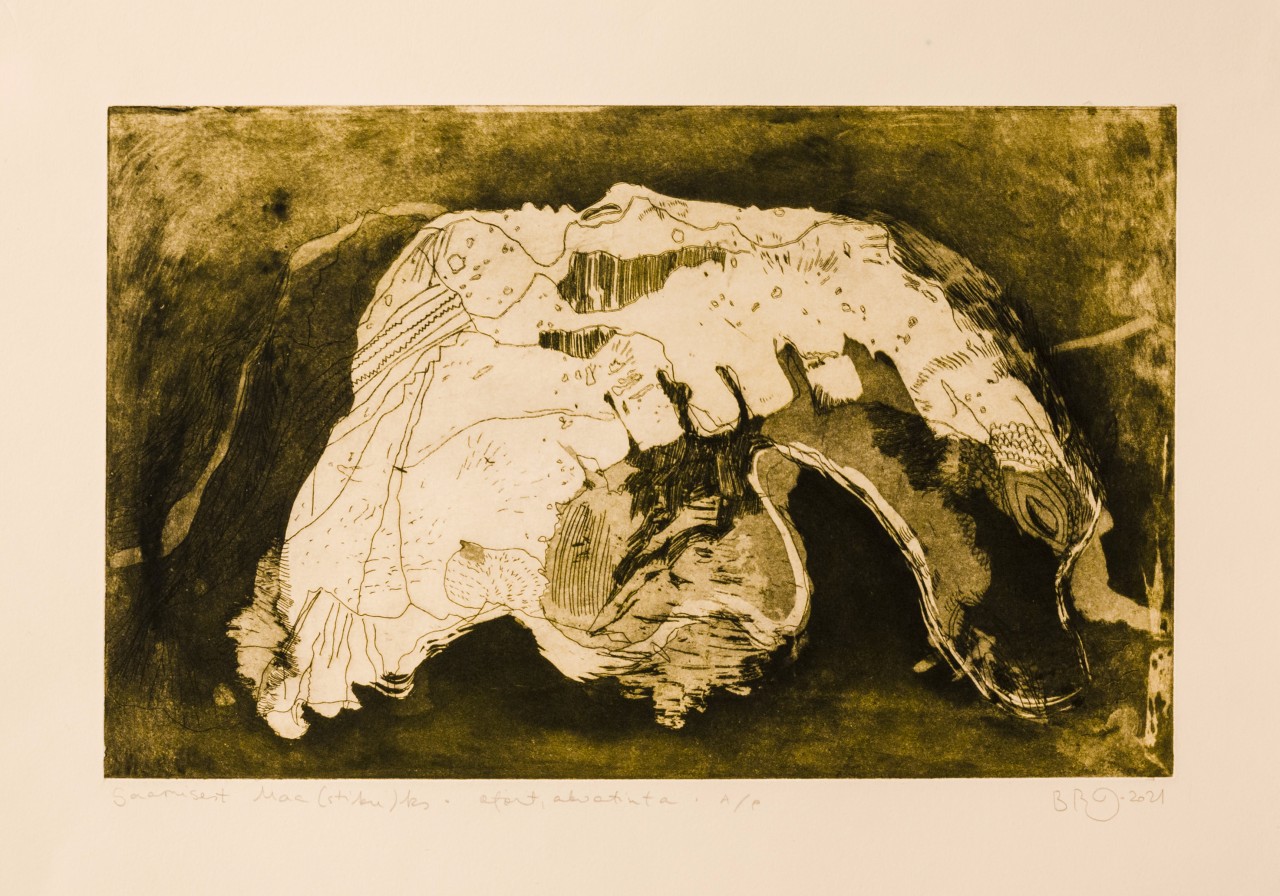

“Of Becoming a Land(Scape)” is her latest solo-exhibition, presented at the large gallery of the Tartu Art House in 2022. There she focuses on landscapes that previously appeared in the background of her artworks. Image is becoming abstract and architecture is backing away from the stage. A layered landscape comes forth, the rocks in the Earth’s crust reveal themselves underneath the soil.

STRATIGRAPHIC FANTASY

At the beginning, the Earth was a large molten stone. Afterwards it cooled down, the magma crystallising into a crust and solid rocks. Even now there is a hot sphere of magma inside the

The paleobiologist Jan Zalasiewicz uses geology to describe what comes after the humankind. By revealing the origin and development of rocks and the Earth’s crust, he offers a geological viewpoint of the future Earth. I use his texts about the development and layering of E/earth as a point of comparison and place them in the context of my artistic practice. Thinking and depicting in layers is my main method of creative research. Zalasiewicz calls Earth a machine of layers, which, unlike its neighbouring planets, and thanks to its hot core, is constantly reacting and in motion, growing and recreating new materials by taking them from a solid state to a liquid one and back

The stratigraphic descriptions of Zalasiewicz are very similar to the technical processes of making art. When I am printing, painting, animating or building installations, I am adding new layers of traces from materials, colours, (conceptual) motions and other means of depiction to a base structure. In printing, I am using different methods and mechanisms of transfer to create imagery. When drawing directly onto the canvas or on paper, I use a tool to create the new layer with a pencil or the tip of a brush leaving its trace.

Sometimes, however, I also remove layers: I erase, wash off with water or tear the textile into shreds.

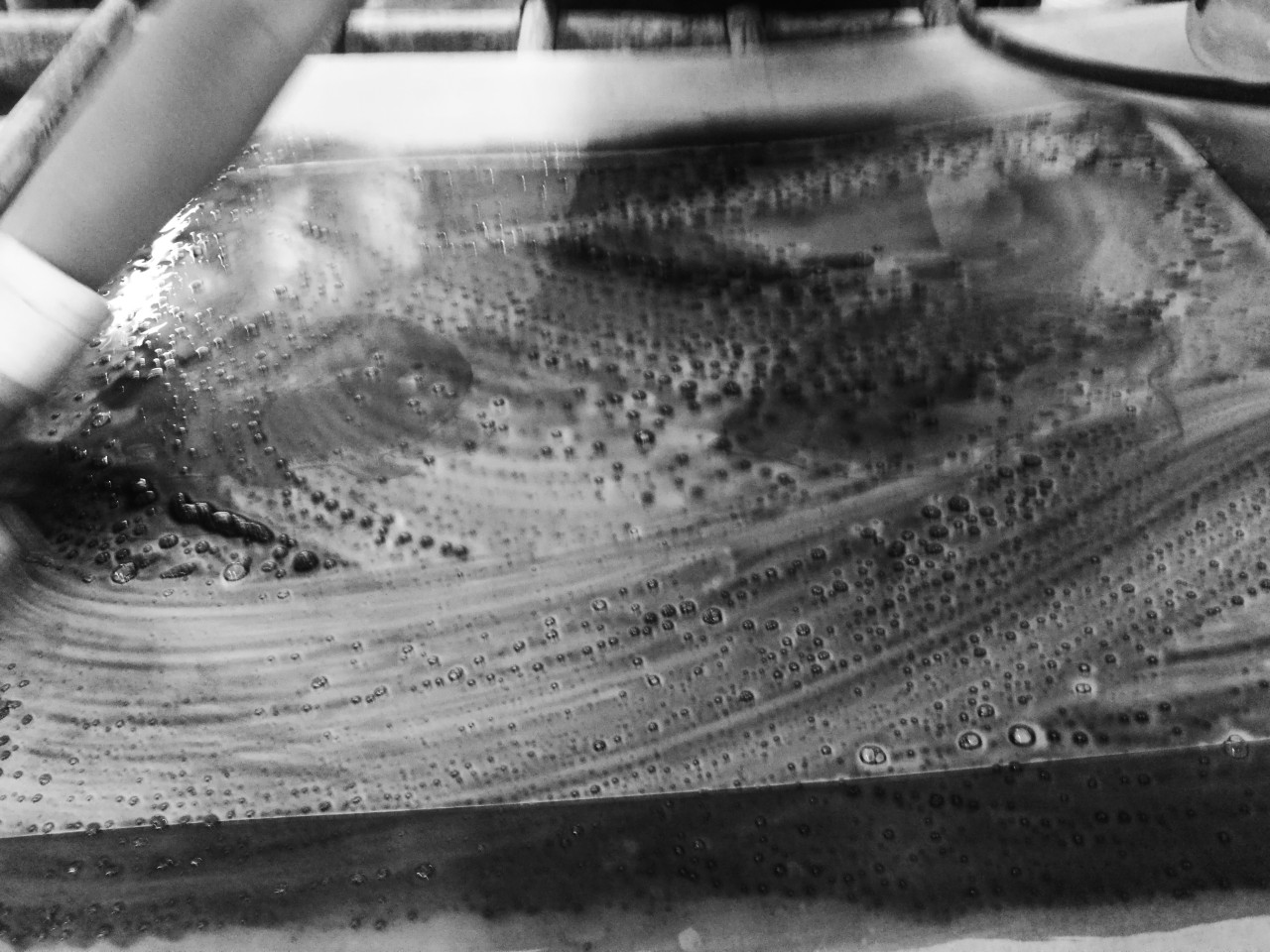

The forms of landscape are developed through erosion, but the creation process of artworks also consists of cutting out and wearing away forms and shapes. The essential nuances of etching are the most pronounced when the metal plate is used for various intaglio techniques. The acid corrodes copper and the surfaces and lines drawn on the plate disappear to be replaced by cavities instead of surface layers.

When I am doing silkscreen printing, I wash off the stencil exposed on the mesh using ultra-violet light: the uncovered areas in the polyester mesh become a clearly delineated shape which lets the paint pass through.

Just like paleontologists can read the cavities inside the rocks left behind by once living bodies and the traces of their lives, we read the cavities, holes, erasures and torn out parts of artworks as elements of a complete image. The spaces between the letters form a silence which talks to us in the same manner as words and sentences do.

What could the Earth be like in a distant future? Compared to the present, it will probably be hotter and covered with more ocean blue. What relicts of our existence could the explores of the post-human Earth discover? The ruins of an old city, the rusted pieces of a car or the crumbs of plastic bags from a landfill? In his book The Earth After Us, Zalasiewicz speculates about the traces we would leave behind, reminding us after millions of years on the geological timescale. Strange chemical and isotopic signals in the rocks will testify to the global transformations that happened during the age of

Every once in a while, the Earth becomes old, crumples up and crinkles into striped mountains. Then again, it is rejuvenated, becoming smoother with landscapes levelling out through the ceaseless rhythm of winds and

When thinking about the Earth, one’s way of thinking also becomes muddy and dark, striped like the geological strata which are not a uniform and monolithic mass, but a stratification of layers with different characteristics. One of the international pioneers of sculpture and painting, Robert Smithson has called the way of thinking that is muddy and imitates the processes of the surface of the Earth “abstract geology”: the spirit and the land are constantly eroding, the power of thoughts moves the abstract shores, ideas dissolving into the rocks of

THE ARRIVAL OF CHAMELEON MEDIA

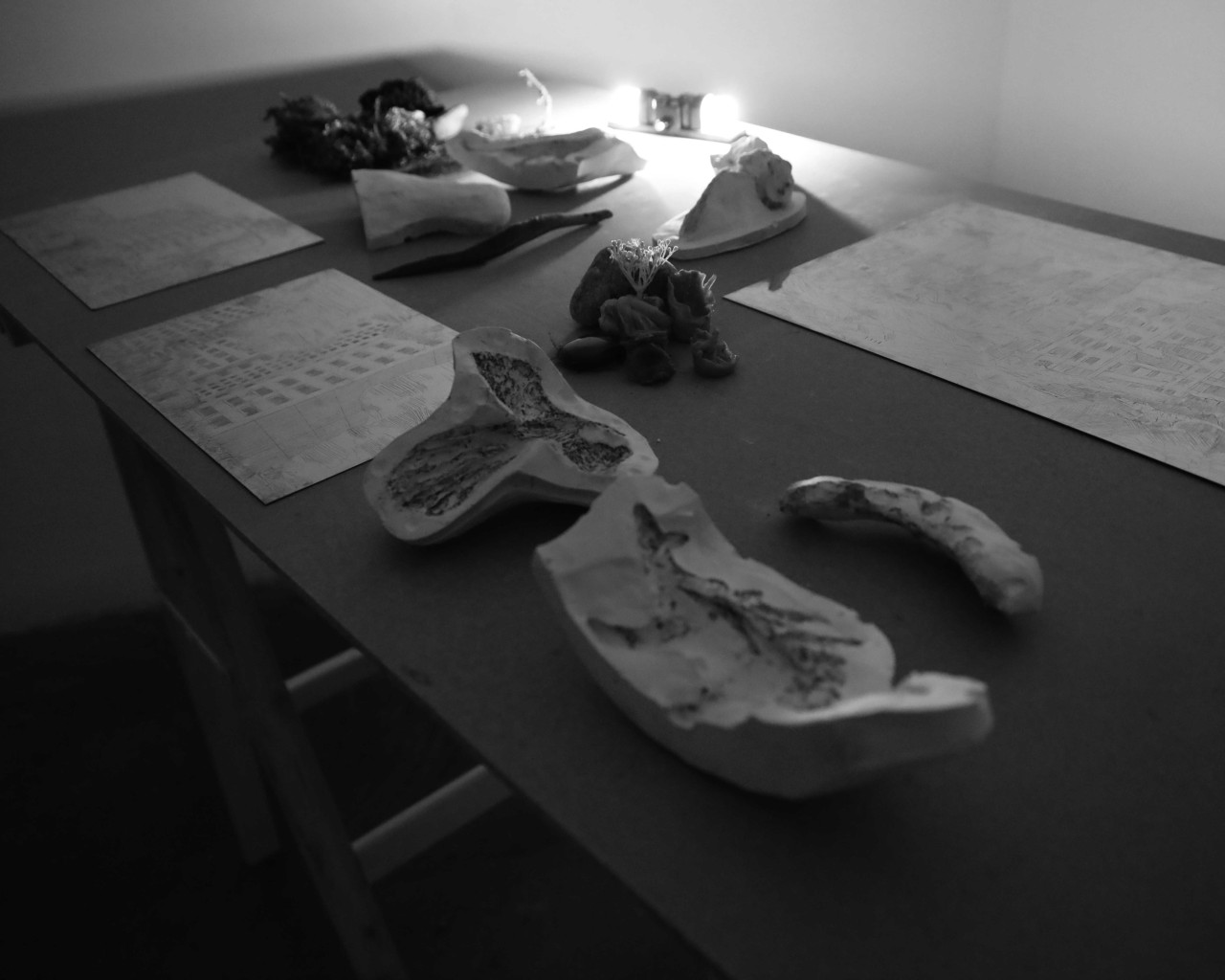

What to call large works that consist of canvas, stretchers and frames, priming, printed images, watercolours, charcoal, acrylic paints, Indian ink and plexiglass? I don’t have a definite answer to that, but the works themselves direct me to use different techniques and materials. I reuse the paintings that I made some time ago: respecting the already existing shapes and surfaces, I carefully cover them with new traces. The existing surfaces point the way for the new lines. The existing work and their materials become the deciders, they are the quiet voice with whom I am having a wordless discussion.

The question of whether one should create new things, including works of art, and why to do it, is more topical than ever in our general overabundance and availability. I’m also troubled by the question of what will happen to my works or art as material objects after the exhibition is over. This question haunts me every time I reach for a new white sheet of paper. Is this truly necessary? What might be the afterlife of this object? The responsibility that goes along with the creation of a work of art is always implicitly there. I have the feeling that maybe nowadays the aim of a work of art is not to be permanently preserved as has been the desire of visual arts for centuries. Besides using sustainable materials to make artworks, it seems also ethical to make art which perishes over time, using materials that are soft and impermanent.

The greyish brown threads of the canvas, which I pulled onto the wooden stretchers, feel warm and soft to the touch although they are strong and sturdy. I fall in love with this material and its colour and abandon the white primer. I print, paint, draw and glue semi-transparent layers onto the canvas. Stains and touches work together. The planned lines and blurry incidents act as conversation partners. The transparent primer reacts to water and changes the colours of Indian ink. We feel each other: it’s not only me getting a hold of the canvas, but the canvas is also getting a hold of me.

In my drawings, I disassemble and reassemble both abstract forms and more clearly defined shapes. Like in a dream, I place the memories on top of each other in layers. The stain and the intentional line – the result of the touch with the bristles of a brush – gain the same importance: “If touch is a mark on the surface that indicates the trace of the material and presence of the hand, then tache is a defamiliarization of the very

The openness and liminality (being in between, on the threshold) of drawing contain the immense potential of transformation, the inherent non-being and hybridisation. Becoming something or somebody feels like flowing or writing: it is a place that requires common construction; it is a time which does not flow in a linear manner. As the post-humanist philosopher Rosi Braidotti has claimed, the process of becoming is not predicated on a stable centralized Self who supervises its

A liminal state as being somewhere in-between or in a state of transition can also be attributed to printmaking. Such states or objects are hard to define because they have crossed the characteristic boundaries of a specific phenomenon but are not yet part of a clearly defined category. It is an uncomfortable state of expectation. The printmaker Tess Barnard defended her doctoral artistic research

Print graphics have been accompanied for a long time by the shadow of the technical approach which does not go deeper into the aspects that are more conceptual, naturalist, philosophical, cultural or

The expanded field of printmaking is transitory and ambiguous, which like a chameleon imitates and includes a wide spectre of media that are hard to

Just like the crust of the Earth which I described earlier, the field of printmaking is like the skin: it is a porous and absorbent medium which imitates or recreates other media through its formally ever-changing nature. Printmaking is breathing and alive like skin, yet it is not like a sponge that allows passive

The printed work is like the skin and the printing the embrace of two bodies tightly squeezed against each

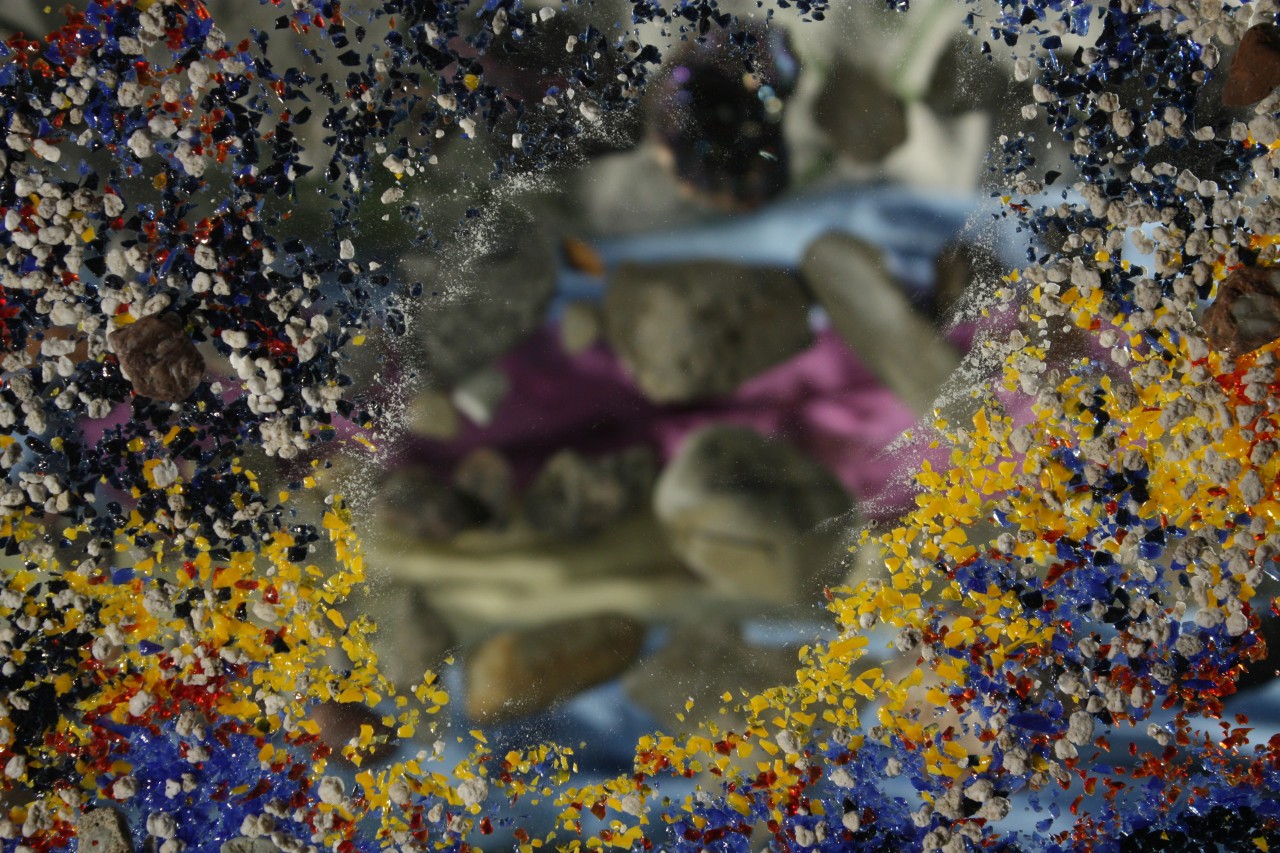

Stones, mountains, holes and landscapes are distorted into colourful shapes both on canvas and on paper but also in spatial installations and cutout animations. In contrast to the warm greyish texture of the canvases, I add shapes cut out of coloured plastic to the compositions. Plexiglass – the sleek, shiny and bright artificial material, i.e. the thermoplastic shatter-resistant polymethyl methacrylate – is laser cut using a previously drawn shape and engraved in freehand. Through this process, the scanned drawing becomes a vector file which can be sent through an application to the cutting machine where the blazing beam will burn the shallower lines onto the surface and will cut a precise shape out of the rigid material using the deeper lines. The pieces of plexiglass will become elongations and expansions of the freely flowing mountains and rocks. The painting moves out of the rectangle of the frame, on it, into the space surrounding the frame. The freehand drawing is converted into a vector format in a way that it acts like a matrix for the following material. Laser cutting is the expansion of printmaking in a shiny and cold new format.

The plastic, textiles and other (found) materials combined into metamorphic rocks deep in the lithosphere create new landscapes of thought. I discover poetically flowing mountains in the heap of blankets on the bed, on topographic maps or in the atlas of non-existent beings.

References

- Jan Zalasiewicz, The Earth After Us, p. 20.

- Ibid., p. 29

- Ibid., pp. 13, 17.

- Ibid., p. 122.

- Ibid., p. xiii.

- Leonid Saveljev, Jäljed kivil. Tartu: Teaduslik kirjandus, 1947, pp. 66–68.

- Robert Smithson, A Sedimentation of the Mind: Earth Projects. – Materiality. Ed. Petra Lange-Berndt. London, Cambridge, Massachusetts: Whitechapel Gallery, The MIT Press, 2015, p. 152.

- Laura Kenner, Stain. – Drawing: The Invention of a Modern Medium, pp 98.

- Laura Kenner, Stain. – Drawing: The Invention of a Modern Medium. Eds. Ewa Lajer-Burcharth, Elizabeth M. Rudy. Harvard: Harvard Art Museums, 2017, pp. 97–105. Citation from: Charles Blanc, The Grammar of Painting and Engraving. New York: Hurd and Houghton, 1874, p. 170.

- Rosi Braidotti, Metamorphoses: Towards a Materialist Theory of Becoming. Oxford: Polity, 2002, pp. 118–119. Cited in: Marsha Meskimmon, Phil Sawdon, Drawing Difference: Connections Between Gender and Drawing. London, New York: I. B. Tauris & Co. Ltd, 2016, p. 80.

- Ibid., p. 88.

- Tess Barnard, S L / \ S H Embodiment, Liminality, and Epistemology in Relief Printmaking Through the Linocut Process. Edinburgh: The University of Edinburgh, 2018.

- Ruth Pelzer-Montada, Introducution. – Perspectives on Contemporary Printmaking. Critical Writing Since 1986. Ed. Ruth Pelzer-Montada. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2018, p. 4.

- Barbara Balfour, The What and The Why of Print. – Perspectives on Contemporary Printmaking, p. 118.

- Ibid., p. 119.

- Ruth Weisberg, The Syntax of the Print: in Search of An Aesthetic Context. – Perspectives on Contemporary Printmaking, p. 63.