Published on 16.12.2024

Jörn Frenzel is a German professor of service design at the Estonian Academy of Arts. He has a background in architecture and over the last 25 years he has worked as an architect, designer and photographer in academic, artistic and business settings. As a co-founder of vatnavinir.is (friends of water) in Iceland, he co-pioneered nature-based strategic design. In his work, Frenzel combines systems and critical thinking to deliver designs born out of complexity and context.

Design, and consequently production, always happen against the backdrop of a wider context – political, social, technological, economic, environmental, etc. This article seeks to raise questions about the context and conditions of design related to production as part of complex adaptive systems, which cannot be predicted or controlled, but only engaged with. It seeks to point designers, and especially aspiring designers and students, to work in a contextual way and critically question their process and outcomes, not only as to their intended outcomes, but their positive and negative feedback loops on social systems, the economic process and the environment. The article also gives an account of recent research on the shortcomings of supposedly sustainable economic concepts – such as zero energy, electromobility, the sharing economy or here for this article the circular economy – and the importance of systemic thinking and context in order to understand the flows of material, energy and other resources in societal production and consumption.

The author supports concepts that aim at planetary regeneration and a radically lower use of resources. However, the answer to our environmental, social and economic predicament must not result in over-simplification, such as simply ‘not to produce’, to simply ‘recycle’ in a closed frame of reference, to simply lower our footprint (to be ‘less bad’) or to produce less in one sector while overshooting in others. The goal must instead be to produce in such a way that things add up across the sheet. Ultimately, overarching social meaning in design can only be produced when integrating various scales and lenses of observation.

... systemic transition requires a shift akin to that of the mobility challenge: simply producing cars with electric rather than diesel engines, yet manufacturing and using them in the same volume, will not reduce the impact of a twentieth-century mobility model. Transformation requires an overall reduction in private car-use counterpointed by an increase in public transport, shared transport and active transport, alongside visionary engaged planning. Mobility is in abundance in either model, but only the latter produces common good outcomes, environmentally and socially.1

The task of design in such a world is to visualise complexity across different scales and lenses, to hold the uncertainty of design outcomes in a dynamic world in different scenarios and to measure the possible outcomes and their meaning for society. Designing things with reliable, adaptive meaning is our job.

The problems with reduction and over-simplification

Few would still argue that production and the economic process can be separated from the planetary biophysical, material, social and environmental realities it is constrained by. This has become mainstream, yet when thinking about production in art and design we often look at the discrete processes of producing a particular outcome and the specific materials and resources used to this end in a closed referential system – usually within our discipline or project of production. In other words, we are largely concerned with the production of particular goods or services and the associated tools and technologies for a particular simplified subsystem that suits our frame of inquiry. Complex issues such as the sustainability of production processes are often reduced to ever new bite-sized concepts with an economic story-line that promises silver bullets for complicated problems. Examples here are solving the problems of economic growth with alleged closed loops (circularity), mitigating energy and resource extraction with mere footprint reduction (zero energy), or countering traffic and emission problems by simply exchanging the engines in vehicles (electromobility) or, as it were, the assumption that solidarity and generosity is simply a business model (the sharing economy).

Concepts such as the circular economy or electromobility have become labels used interchangeably with the term sustainability. However, circularity is not sustainability.2 Circularity or electromobility certainly can and should play a part in achieving sustainable goals, but they are not the same thing. As humans and societies, we need to simplify to some degree in order to communicate and to save our energy and time; but oversimplification and reductionist concepts will result in useless and potentially counterproductive buzz wording and un-reflected zeitgeist. Consequently, we have to explore how complex we need to go in our frames of inquiry or, vice versa, how much simplification can we allow ourselves as designers in order to produce something useful and meaningful.

Issues with simplification in teaching design in academia

When talking about over-simplification in production and design, there are several strategies to address environmental issues that can be observed in academia and education itself. One strategy relates to a current occasional reluctance on the part of designers to produce original goods or artefacts, since adding to human production and consumption are conceived as part of our ecological and social dilemma. The role of design as an integral part of production is supposed to either integrate into larger cycles or processes, or to even render itself invisible in certain ways. Circular design, in reality, is part of the larger narrative of a circular economy that is understood as an economic process based on perpetual recycling, repairing and reusing energy and materials, closing the material loop within a production system, and thus decoupling material and energy flow from economic growth. The individual circular (ecological) patterns, however, are not understood as part of a larger economic process or the societal metabolism consisting of different sectors and subsystems. Life cycle assessment (LCA), for instance, analyses the value chain of one design outcome (a car, a building, a pair of trousers) along its life stages, but does not consistently regard system boundaries and feedback loops with other systems.

Alternatively, the role of the designer itself is changing in the context of the post- or de-growth strategies in which designers are not to produce more, but less. Designers become, for instance, resilient gardeners3 that produce modestly and coexist with natural cycles in perfect and small worlds of ecology detached from the greater economic process of society. This strategy of ‘folding the butterfly of the circular economy’4 – that is, combining technical stock management and renewable flows, repair with maintenance, etc. – is often done within the constraints of one’s own discipline or one’s individual projects. The attempt to make a transition from extractive to regenerative practices is important, but again happens in national, regional and global contexts. Degrowth has to happen in the context of a still growing global population (even if plateauing is on the distant horizon). Any strategy for, say, local food production has to recognise that only a fraction of humanity (in the Western world) could live on locally produced organic food.

Both of these strategies have their limits – the former has recently been increasingly criticised due to biophysical impossibilities,5 and the latter is not answering the question of how strongly localised design strategies might be scaled to globally. Furthermore, both narratives remain stuck in an economic language. Circularity or post-growth concepts have their place within the larger goal of regenerative design practice. It remains problematic, however, that they partly create over-optimistic scenarios as regards sustainability, underplay scientific principles of energy and material loss, and restrict themselves to economic terminology. Green growth is still growth and degrowth is still using economic vocabulary to structure its thinking. Education and academia are the spaces where a departure from old terminologies and mental structures can happen, where new group narratives can be born. These new narratives all end up in discussions on multiple scales. If these approaches embrace complexity and multi-level inquiry they have a better chance of fostering deeper meaning.

Explaining the bottled water studio

In order to study the great complexity of seemingly simple design challenges, in spring 2024 students of various design specialties at EKA enrolled in a studio course on Sustainable Design, which focused on the topic of bottled water. The course instructors – Stella Runnel and the author of this article – chose this topic as it exemplifies the complex entanglement of various systemic issues in a simple product. Students opened up the many scales and implications of water in single-use plastic bottles, ranging from health issues (microplastics) to water-carrier designs of the future, all the way to campaigns for better public drinking water systems avoiding single-use plastic bottles. Hence, this design studio looked at the different scales of the problem with different tools. The students discovered that the water sold as mineral water is very often simply re-bottled tap water (micro level), that it takes up to 5–8 litres of virtual water to produce a 1-litre-water-bottle (medium or meso-level of production) or that EU regulations focus on standards for water bottle caps, while failing to promote different water policies (macro-level). The different scales of production were considered by re-conceiving minimalist interventions to influence user behaviour (micro-scale); challenging the (unsustainable) production of bottled water through the promotion of community-based, public water sources (meso-scale) and opening up international implications of water consumption (macro-scale).

The outcomes reflected the different scales and lenses of inquiry: one group designed speculative new objects of personalized water transportation and consumption in the future and designed containers inspired by biomimicry; another team developed speculative scenarios and prototypes in a practice-based research on user behaviour and preferences related to tap water and single-use bottles; yet other teams created campaigns, services and interactions targeting the network of public water sources for international visitors or ‘tap water bars’ as communal, non-commercial meeting points and poignant, humorous vessels of critical discourse.

Lessons learned and outlook

In the Bottled Water Studio, we worked on different orders of design6 from the production of films and graphic materials to designing objects, public water services and systemic notions relating to the wicked problem (in Horst Rittel’s sense) of sustainable water use in society. Gigamapping7 and system-oriented design, two design frameworks for system innovations and transitions,8 have proven effective methodologies and frameworks to avoid simplification and introduce multi-scale inquiry into design studies. The challenge for students is often to maintain a rich picture of scales and representations (text, images, diagrams, etc.) and the complex feedback loops and connections within them. The temptation to solve overarching societal problems instead of deep diving into the intricate complexities of production, usage, and communication in a basic context, such as drinking water consumption, remained an ongoing challenge. Zooming in and out of scales and traversing the different system boundaries helped overcome this bias and proved productive for the course.

The usefulness and impact of systemic and multi-scale design on our systems of societal production depends upon our willingness and ability to deal with what Dan Hill has called the Dark Matter of design. He talks about the unknown, often hard-to-grasp, strenuous and even boring stuff surrounding our first, second or even third order design products – the matter; he stresses the importance of getting into the nitty-gritty of policymaking, actually measuring the real impact our design concepts have, or engaging in system-oriented conversations about what sustainability might mean in very specific cases, abstaining from silver bullets and solutionism.9

Over the past 120 or so years, the scope of design has gradually changed. From text, signs, products and brands to services and interactions and systems and strategies. This refers to an increasing complexity of individual design tasks, but does not yet answer the need for complex, multiscale analysis across sectors or scales in complex adaptive systems. If we are to engage communities and measure impact, then marrying design methodologies with scientific rigour and accountability – or literally accounting10 – may be one of the possible answers. In Mario Giampietro’s words, the most important role of universities nowadays is ‘... to involve the society in the formation of a new group identity because... this is not about technology or business models... We have to move from producing and consuming goods and services to taking care of ourselves and nature.’11 Integrating quantitative, science-based storytelling with qualitative design methods would hold considerable communicative and creative potential in building robust design frameworks with deep meaning.

Student outcomes

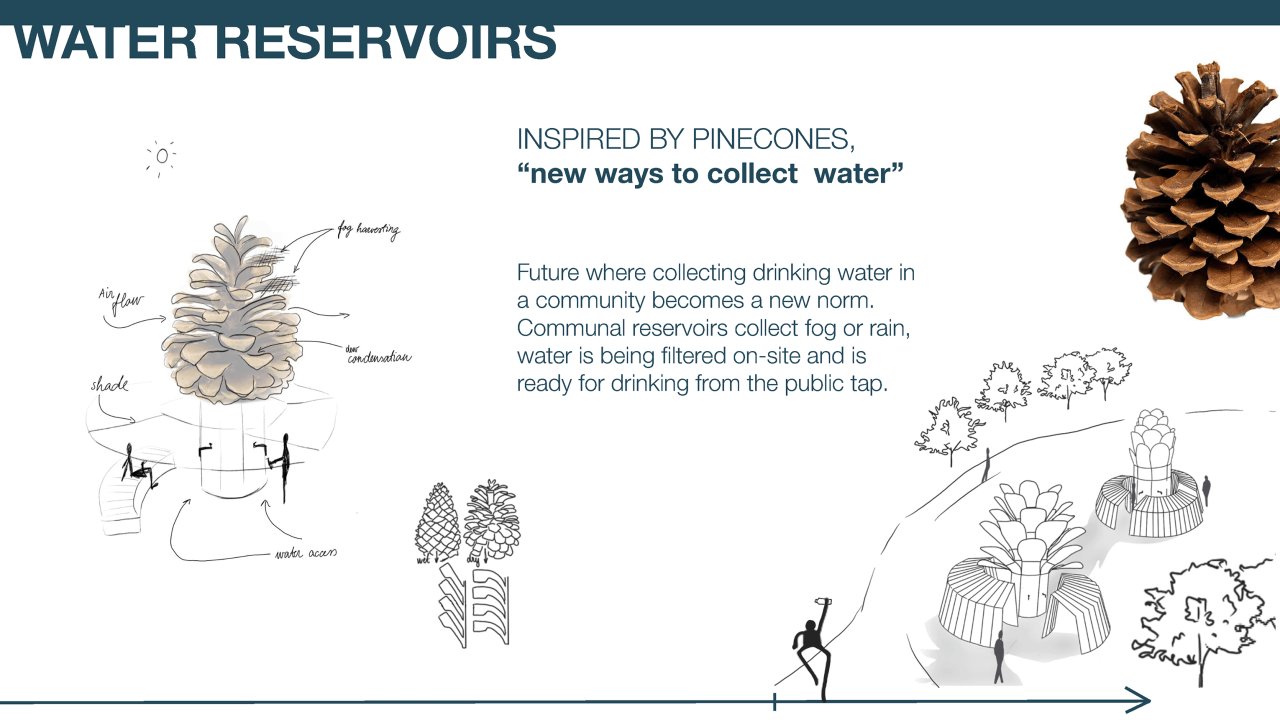

Team ‘Future of water’

Doreen Mägi, Katrin Lepa-Ruben, Maarika Piirimees-Juurikas, Susanna Belinda Kõgel

The students created options for public indoor water stations that are easily accessible all year round, to be implemented from 2030–2050, and added speculative design sketches on how to carry and store water individually in times of water scarcity.

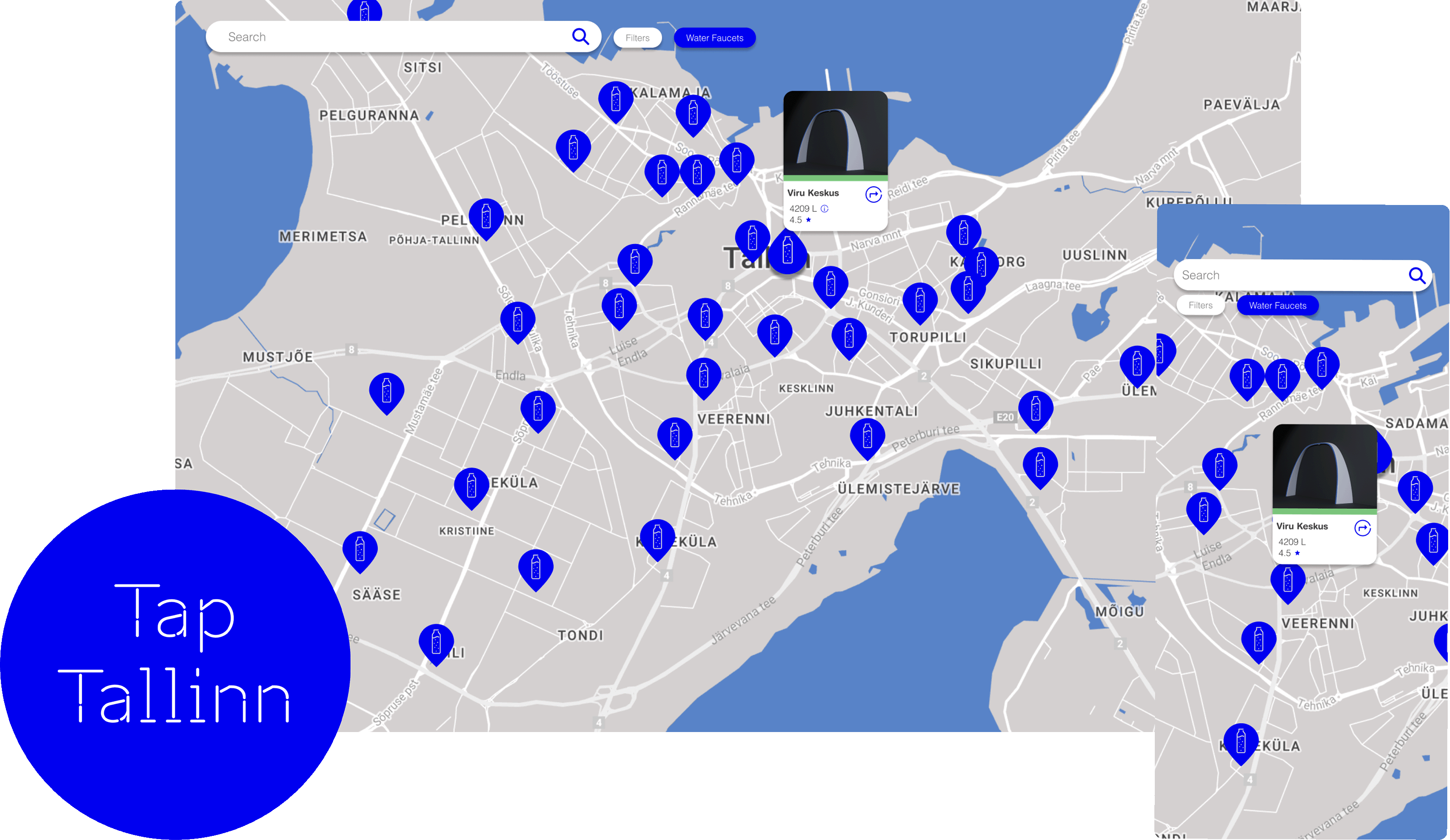

Team ‘Tap Tallinn’

Maris Vahter, Sandra Luks, Nika Aduashvili, Emma-Liisa Kalvik, Liina-Mai Kaunissaare

This project was a self-organised cooperation with Tallinna Vesi and Visit Estonia to create a proposal integrating information, maps and product design for public water taps around Tallinn, targeting the partner organisations’ communication challenges as well as international tourists specifically.

Team ‘Wicked Water’

Mirjam Mõttus, Annu Muiste, Eva-Liis Lidenburg, Jan Teevet, Alyona Movko-Mägi

This work targets the wider issues around water as a commodity; in a poignant, humorous and performative way the students created places and services around them serving free tap water, inviting public discourse around the topic of just and environmentally responsible drinking water usage.

Illustration: AI

Team ‘Minimalism and experimentalism’

Kaisa Moora, Eva Reiska, Kerttu Reinmaa, Claire Mathieu, Carl-Eric Uibo

On a micro level, this project aims to facilitate and encourage the use of existing tap water infrastructure for university students and employees at EKA, experimenting with alternative bio-materials at the same time.

References

- Dan Hill and Mariana Mazzucato, ‘Modern Housing: An environmental common good’, Council on Urban Initiatives (CUI DP 2024-02). UCL Institute for Innovation and Public Purpose Working Paper Series: IIPP WP 2024-03

- Tom Bosschaert, ‘Circularity is not sustainability: How well-intentioned concepts distract us from our true goals, and how SiD can help navigate that challenge’, in The Impossibilities of the Circular Economy, ed. by Harry Lehmann, Christoph Hinske, Victoire de Marjerie, and Aneta Slaveikova Nikolova (Routledge, 2022).

- <https://www.artun.ee/et/kalender/eka-doktorikooli-konverents-2024/>

- <https://www.ellenmacarthurfoundation.org/topics/circular-economy-introduction/overview>

- Reinier de Man, ‘Circularity dreams’ and Mario Giampietro, ‘The entropic nature of the economic process’, in The Impossibilities of the Circular Economy, ed. by Harry Lehmann, Christoph Hinske, Victoire de Marjerie, and Aneta Slaveikova Nikolova (Routledge, 2022).

- Richard Buchanan, ‘Worlds in the Making: Design, Management, and the Reform of Organizational Culture’, She Ji: The Journal of Design, Economics, and Innovation, 1.1 (2015), pp. 5–21.

- Birgir Sevaldson, Designing Complexity: The Methodology and Practice of Systems Oriented Design (Common Ground Research Networks, 2022).

- Fabrizio Ceschin and Idil Gaziulusoy, ‘Evolution of design for sustainability: From product design to design for system innovations and transitions’, Design Studies, 47 (2016).

- Dan Hill, Dark Matter and Trojan Horses: A Strategic Design Vocabulary (Strelka Press, 2012).

- Refer to Mario Giampietro, Kozo Mayumi, and Jesus Ramos-Martín, ‘Multi-scale integrated analysis of societal and ecosystem metabolism (MuSIASEM): theoretical concepts and basic rationale’, Energy (2009), 34.3, pp. 313–322. <https://doi.org/10.1016/j.energy.2008.07.020>

- <https://www.thegreatsimplification.com/episode/107-mario-giampietro>