Published on

30.06.2023

Ulvi Haagensen was born in Australia but has been living and working in Tallinn, Estonia for many years. She studied at City Art Institute in Sydney (BA) and College of Fine Art, University of NSW (MFA) and is currently a PhD candidate at the Estonian Academy of Arts. Her practice and research looks at the connections and overlaps between art and life, as seen through the eyes of an artist, for whom art, work and everyday life are closely interwoven.

I walk into the kitchen a little bleary-eyed. It’s dark outside and far too early. I’m barefoot and step on something hard. It’s one of the cat’s biscuits. Why can’t she eat more tidily? She manages to lick herself clean, why can’t she learn to lick the floor clean? We should teach her to use a broom.

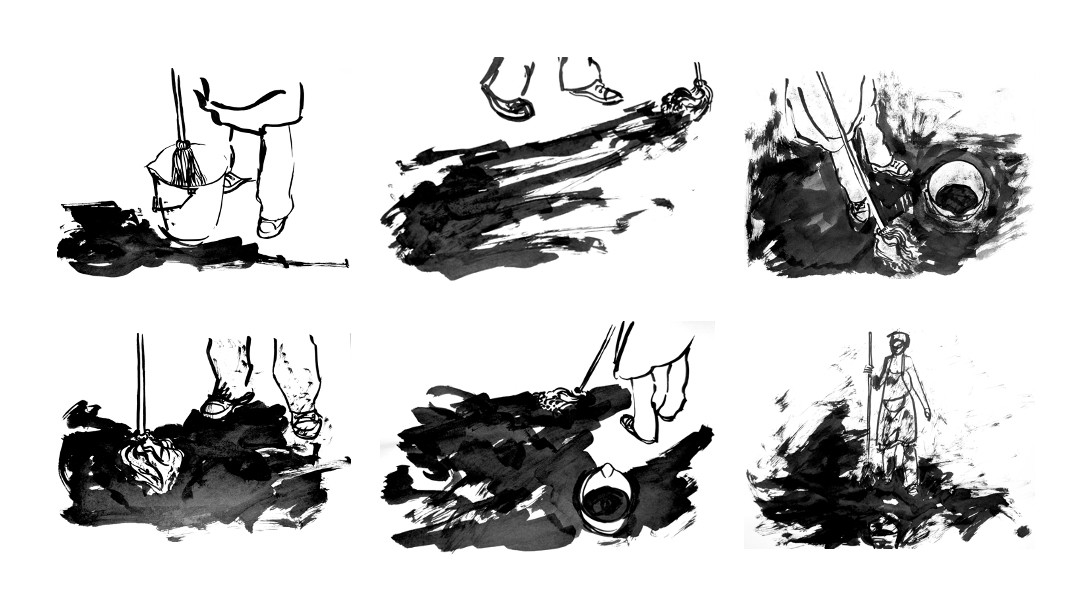

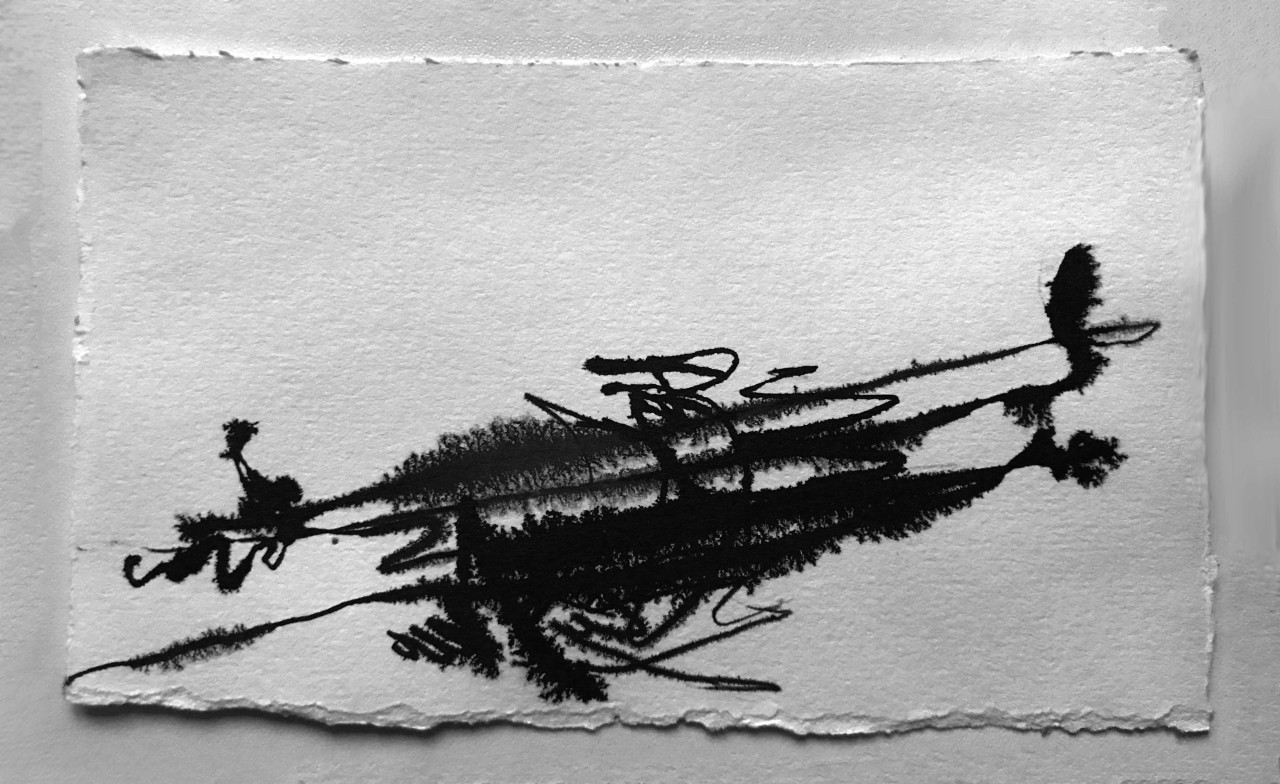

I began thinking seriously about cleaning when I started my PhD in artistic research at the Estonian Academy of Arts in 2016. Up to that point I had of course been doing it as part of everyday life and at some stage it had started to creep into the subject matter of my art installations with objects that looked like vacuum cleaners, tea towels and other things related to cleaning and domesticity. I had also drawn on the floor and walls of galleries and then ended each of those exhibitions by cleaning away what I had drawn. But it was a comment I once overheard at one of my exhibitions along the lines of ‘cleaning not being art’ that intrigued me and provoked me to explore this idea further. I was quickly overwhelmed by a flurry of questions about what is cleaning, why do I do it, how do I do it, what do I clean, how do I know when something is clean and what even is dirt? In my search for the answers, I started to clean, as art. I performed cleaning with my own homemade cleaning tools – brooms, brushes, cleaning cloths, feather dusters – and wearing my own homemade aprons, housecoats, headscarves and hats. If I framed the cleaning in a performance that was separate from everyday life, I might be able to see cleaning, dirt and what it was that I was doing more clearly.

Before I talk about what I discovered through these cleaning performances, I’d like to look at cleaning more broadly by looking at some of the reasons people clean. One obvious and very practical reason is because we want to clear a space, to get something out of our way, to make space. A footpath for example, will be swept to make it obvious where we are supposed to walk, so we don’t trip over obstacles or slip on rain-soaked leaves. In István Szabó’s film The Door, based on Magda Szabó’s semi-autobiographical novel of the same name, the character Emerence, played by Helen Mirren, is seen many times throughout the film sweeping the footpath outside her house and that of her neighbours. In autumn she sweeps leaves, in winter she sweeps snow. Throughout the film we keep coming back to her sweeping. It’s a task that needs to be repeated.

Another reason is for hygiene; cleaning and the end result – clean – removes germs and bacteria and also communicates the notion of health and our belief in its importance. The connection between cleanliness and health is revealed in the words sanitary and sanity. Both derive from the common Latin root sānitās meaning health.

Failing to look after our bodies and our surroundings can be a sign of disorder, and can reveal itself as physical, mental or emotional ill health, and maintaining order can help to keep these ills at bay. As Szabó’s film progresses, we become aware of Emerence’s traumatic past that continues to haunt her. It seems she wants to restore something. As she sweeps her shoulder, arms and head move rhythmically with each energetic stroke of her broom. Her sweeping is vigorous and slowly becomes a symbol of her battle, as though by sweeping she will right all the wrongs. Chaos and uncertainty are frightening. The repetition of her strokes and the sweeping as an activity repeated through the changing seasons is a kind of ritual to provide structure and reassurance. Kathleen Norris explores the connections between mundane domestic tasks and spirituality in her book Quotidian Mysteries: Laundry, Liturgy and Women’s Work and draws a parallel between religious liturgy and domestic chores, stating that they ‘serve to ground us in the world’. In other words maintaining contact with the mundane everyday world can provide a stabilising sense of our physical presence in the physical world. And a sense of order is also aesthetically more pleasing. Cleanliness also communicates care – care for others, our surroundings and ourselves.

It can also be an expression of an attempt to do the right thing, to be good and do what is expected of us. Parents, grandparents, other relatives, endless books and YouTube videos endeavour to instruct us in the most efficient and often correct way to clean.

But cleaning can also be arduous and seem completely pointless. On a day-to-day basis the repetition of cleaning can seem like a waste of time; I sweep the floor but know that tomorrow I will need to do it again. So, why not leave it until then? Why do it at all? Simone de Beauvoir writes that ‘Few tasks are more like the torture of Sisyphus than housework, with its endless repetition: the clean becomes soiled, the soiled is made clean, over and over, day after day.’ Sometimes when I use the vacuum cleaner I start off innocently thinking I will do something good, something useful, something no one can argue with, but slowly as the vacuum cleaner gets stuck behind furniture and its hose gets caught on a door handle my mood changes and an engulfing rage overcomes me. ‘Why me? Why am I cleaning again? Why do I have to do it?’ I rage against the apparent unfairness of it all like all the raging feminists fighting against the unfairness of cleaning falling predominantly on the shoulders of women (and other marginalised groups). Françoise Vergès’ book A Decolonial Feminism begins with the very apt question ‘Who cleans the world?’ and focuses on the difficulties faced by underpaid and undervalued cleaners working in the cleaning industry.

Put the vacuum cleaner away and hand me a broom, especially one of those birch besoms, and it’s a different story.

I am sweeping the path and I feel completely present. I feel the smoothness of my broom handle as it slides through my hands at the beginning of each stroke. I feel its firm perfectly round evenness as I resume my grip. There is a vibration through the handle as it passes across the rough path. The loose gravel kind-of rattles… tchuck, tchuck, tchuck… across the hard surface of the ground. I continue to sweep here just to enjoy the sound. Then in the distance I hear a train passing and suddenly my awareness shoots out far beyond the boundary of my myopic focus on the ground. Jerked out of my small private bubble into the large open space of the cemetery I am now thinking about the train and how it sounds sad, like a Johnny Cash song, but as I continue sweeping I become re-absorbed by each stroke of my broom and once again forget where I am.

I have never used a leaf blower and it doesn’t look like much fun. The grinding-whining sound is so machine-like and disengaged from its surroundings. The birch twigs of my besom make contact with the ground and I feel that I am present. Its bouncing flex against the ground and rhythmical swish-swish tell me I am here. Maybe I should go to each person out there with a leaf blower and gift them one of my birch besoms.

But not all brooms feel good. I once borrowed one that was too short for me. I was filming myself sweeping and worried that the short broom made me hunch over. I worried that I looked like an old woman, which is a stupid thing to worry about because what’s wrong with old women? I’m going to be one one day. I’m not the only one concerned about how I look when I’m cleaning. Once when I walked past the recycling bins in the carpark on the edge of the park there was a group of workers. One man with a leaf blower was blowing the sodden leaves into a neat pile. A woman leaning on a broom was watching. She had heavy, dramatic eye make-up and looked quite glamorous. She reminded me of the cleaner at the shopping centre, who dispiritedly and somewhat carelessly pushes her broom around, but has carefully drawn eye make-up. I guess we all want to look our best, whatever we are doing.

The odd thing about cleaning is that it is most obvious when it hasn’t been done. While living in Sydney from 2018–2019 with my family we did a number of what are called house-sits, which is when you look after someone’s house while they go on holiday. On arrival these homes were very tidy and looked naturally clean, as if the clean belonged to the place and wasn’t because someone had cleaned it. After a week of living there, I realised naturally clean does not exist. There was a noticeable accumulation of dust and traces of our everyday activities. The owners had obviously put a lot of effort into preparing their home for us and of course the level of cleanliness was also a hint that this was how they expected it to look on their return. In the same way that cleaning is invisible so too are cleaners. Raging against the injustices and inequality experienced by professional cleaners Françoise Vergès writes with irony that: ‘This work [cleaning], indispensable to the functioning of any society, must remain invisible. We must not be aware that the world we move around in is cleaned by racialized and overexploited women.’ Cecilia Vallejos and Matthijs de Bruijne writing about making the cleaners’ movement in the Netherlands visible say that:

…one of the characteristics of the cleaning sector was that the cleaners worked in empty offices or trains at night and were hardly ever seen by others. Because of this, and because they constituted an all but invisible labour force, the new form of representation [that the Union of Cleaners were aiming to put into practice] had to be powerful enough to catch the attention of wider society.

Their slogan became ‘Never Again Invisible’. And then there are the paid domestic cleaners cleaning someone else’s home who are invisible because they are working in private homes, often when the owners are out.

My cleaning is my own and relates more closely to the invisibility of unpaid domestic cleaning that is performed in the family home. As Meg Luxton wrote as long ago as 1980 (but still relevant today) this is ‘both private and unseen… [and ]… rooted in the intense and important relationships of the family, it seems to be a “labour of love” and therefore is neither understood nor recognised as work’. However, despite my work not being recognised as work and enjoying a shared rage with a vast number of other people, most of the time cleaning does not make me angry, especially when I am doing cleaning as art or cleaning as research. This is because my focus is not so much on the socio-economic and gender aspects of cleaning but I am closer to home looking at what is happening right here at the point where my broom brushes the floor or the kitchen cloth wipes the kitchen bench.

The rage I felt earlier when I hoicked and wrestled the vacuum cleaner around my apartment also subsides when I remember something else about cleaning. It’s not always necessary and it’s not always good. David Foster Wallace in his essay A Supposedly Fun Thing I’ll Never Do Again, describes what can happen when cleaning is taken to excess and how unsettling this can be. He is on a cruise and describes the mysterious ability of his cabin steward to invisibly clean his cabin. She ‘cleaned my cabin within a centimeter of its life at least ten times a day but could never be caught in the actual act of cleaning.’ Every time he returns to his cabin it has once again been cleaned and his varied attempts to catch her in the act invariably fail. In the beginning he enjoys the perpetual state of order and cleanliness. But what originally starts out as apparent concern for his comfort ends by making him uncomfortable, especially since the cabin steward is cleaning because it is her job. He likens her to an overzealous host who is constantly tidying, laundering and cleaning up after you. Pleasant at first, until you realize they are merely acting out their ‘personal neurosis having to do with domestic cleanliness and order’ and in fact they will be glad when you leave.

And some cleaning is not only unnecessary but also just plain wrong. I was once sweeping outside a house with a garden and driveway and filming myself at the same time. I intended my sweeping to be a form of service, a gesture of goodwill, real cleaning instead of performing-for-the-camera-type-cleaning. The gravel on the driveway was satisfying to sweep until I stupidly realised it was there for a purpose. The owners had probably paid someone to bring that gravel and spread it across the drive. All loose things on the ground don’t need to be cleared away. I carefully swept it all back in place, as evenly as I could.

Some cleaning might just be habit. In The Simpsons Movie, minutes before their home is about to be destroyed by fire, Marge Simpson rushes back inside to get something important from a locked cabinet in the kitchen. On her way back she passes the kitchen sink, sees a dirty plate, quickly washes it and places it on the drying rack to dry and then continues her flight out the door. Maybe Marge is obsessed with cleanliness or maybe it’s nothing more than a deeply ingrained habit. Emerence, however, does appear to be obsessed. During a snowstorm when the snow lies thick on the ground and is continually being replenished by more snowfall it becomes obvious that her sweeping is no longer about clearing a path. Maybe it is a defiant act against the forces in her life she has little control over. Despite being ill she continues to sweep, even though it is a pointless task that she can never hope to finish. When her kindly neighbour asks her to stop because she is obviously sick she says, ‘Go away. Can’t you see I’m busy’?

Cleaning can be a good method for avoiding something, like Emerence avoiding the harsh realities of her life. Or it may be a way of putting off something, like the writing of a visual essay, in other words a procrastination tool. This avoidance is often regarded in a negative light, but it could also be seen as a run up to something or a form of preparation – a mindless task in readiness for a mindful one. The writer Elizabeth Jolley preferred to get her domestic tasks out of the way before she sat down to write. She says it was part of her need ‘to create a superficial order in my surroundings before I can confront the confusion which exists in my mind’. And it can also be useful if I want to pretend to be busy.

And if you are looking for conflict, then cleaning is good for that. It’s a constant source for disagreements over whose turn it is or how well something has been done. Cleaning can also be used to annoy someone, to give them a message, to shame, belittle or even punish them. Think here of the stereotypical image of the hardworking housewife-martyr noisily vacuuming right in front of the television that her lazy husband is trying to watch. I once overheard a story about a woman who deliberately washed her husband’s expensive new cashmere jumper in the washing machine on a hot cycle as punishment for something he had done. The jumper shrank.

Sometimes cleaning is like a performance, as in Ilja and Emilia Kabakov’s story The Short Man.

Everyone in our apartment knows that when it is Sokolov’s turn to sweep the kitchen, that it’s more like a performance than simple cleaning. He doesn’t miss one scrap of paper, not one rag, not one piece of match, – everything will be examined very carefully, investigated, and carried away to his room and hidden.

Although like a performance this is still real and meticulous cleaning, done with the seriousness employed by Emerence. In another film, this time the work of the Japanese filmmaker Yasujirō Ozu called Tokyo Story the sweeping at the very start of the film is more about setting the scene of everyday domesticity. There is a short sweeping sequence with a long handled soft broom that bends and flicks as the woman uses it. Her broom appears to have a weight to it. The bristles flex and move together in a deliberate downward movement as she brings the broom down against the floor. After each stroke she lifts the broom and the bristles rise upwards, lightly and effortlessly. The sequence comes to an abrupt end when she finishes off with a few light rapid flicks of the broom and walks off out of shot. She returns, minus broom, to pick some books up off the floor, and then takes a cloth drying on a railing and starts to fold it by flicking the cloth back and forth on itself. Once folded onto a low sideboard she immediately turns to a cloth and bucket on the floor, wipes a few circular motions with the cloth and then picks up the bucket and leaves the room. These few flicks of the broom, the wrung out cloth; it’s more of a suggestion. The actions are easy, even a little careless. It’s more about showing that someone is cleaning, rather than actually cleaning.

However, what starts out as a performance, in front of an audience or for the camera, soon crosses a line between real and non-real cleaning. The broom moves in the way that a broom should and in the process finds things to push or pull. It finds gravel, sand, tiny pieces of plastic, bits of paper, maybe a rusty screw. As I identify what each individual thing is I become involved in an exercise of choosing and sorting. Do I sweep this thing or leave it behind? On the grey gravelly ground with my bright blue and red broom I started to notice all kinds of colourful tiny pieces of rubbish. It feels as though my colourful broom has suddenly tuned me in to finding them. Because most of them were plastic I wondered, maybe I should pick them up and throw them into a rubbish bin and remove them from this otherwise natural looking grey environment. I have also found that once I start sweeping an apparently clean place the dirt appears. The broom finds it and I realise the place I had assumed was clean, wasn’t. It never is. There is always dirt.

And what happens when we go to all this effort and clean something that is already clean or spend our time cleaning something that does not need cleaning, such as wiping an already clean kitchen bench or pointlessly sweeping a patch of dirt in the forest or jumping into the swimming pool to do a bit of cleaning. And what about if the floor is just a little bit dirty. Is it a waste of time to wash something that is only slightly dirty? How much dirt do I need, to be able to justify cleaning.

What makes dirt dirty? It has a lot to do with context. Mary Douglas’ oft-quoted idea about dirt is that it is ‘matter out of place’. Asad Raza’s work Absorption at the Carriage Works in Sydney was a room filled with soil. It smelled earthy and was soft and springy underfoot. It was good, it had potential. Dirt on the other hand doesn’t have optimistic potential in the way that soil does. But soil can quickly become dirt when it is brought inside as muddy footprints. It’s the context that makes the difference. Similarly, the jam on my toast is food until it falls onto my freshly ironed linen shirt. In other words, dirt is the wrong thing in the wrong place, and probably at the wrong time.

And sometimes cleaning can actually make things dirtier. After mopping the floor, the water in my bucket is dirty and after mopping the ground in an as yet undeveloped part of town, a kind of wasteland area, my bucket is full of mud and the pristine white strings of my mop are completely filthy. The dirt has simply moved from one place to another. And speaking of very dirty things there was an award-winning tractor driver in Soviet Estonia, who was known for having the cleanest tractor. Imagine how filthy her tractor must have been from working in the fields, and not only did she clean it but also decorated it with flowers.

And what happens when I don’t take cleaning seriously but treat it like a game? In 2018, I organised a participatory sweeping performance. We swept as individuals and occasionally, collaboratively. It was windy, which made the sweeping quite pointless, even absurd. As soon as I had managed to sweep together a pile of leaves the wind would undo all my work. At one stage I chased a single leaf for a time, attempting to have it join the other leaves only to have the wind blow it away. Someone else vigorously swept the leaves into piles, only to have the piles blow away. But occasionally the wind collaborated and blew the leaves into the right place.

Cleaning can also be quite meditative. There was a workshop in Sydney, a Butoh workshop, where we were learning to walk. At the start of each day everyone washed the floor together – Japanese style, with hands on the floor and bums in the air. It was a way of preparing physically, so the floor would be nice and clean, but it also instilled a sense of mental, and possibly spiritual readiness. Shoukei Matsumoto, a Shin-Buddhist monk writes, ‘…for monks the physical act of polishing floors is analogous to cleaning the earthly dirt from your soul. This grime accumulates in your body and poisons your mind.’ I wanted to try this type of cleaning again, this time on my own. So, I washed my way from one end of the room to the other and then back again, the wet marks overlapping with the previous line. Long deliberate strokes that leave a clearly visible wetness, back and forth, back and forth, back and forth.

Cleaning can also have a calming effect and act like an anchor in moments when we are rattled or disturbed. Towards the end of Haruki Murakami’s novel 1Q84 one of the main characters is overwhelmingly agitated by the anticipation of meeting someone. He cannot seem to settle and is unable to read or write – being a writer these were quite normal activities for him. He could not sit still. ‘The only thing he seemed capable of doing was washing the dishes, doing the laundry, straightening his drawers, making his bed.’ A sense of calm is communicated in yet another film, actually a television series. In David Lynch’s Twin Peaks: The Return, Episode 7 we see the floor in a bar being swept. It’s a long scene and therefore quite unlike the introductory scene in Ozu’s Tokyo Story. A man sweeps the floor with clearly visible rubbish scattered across it. Unlike Ozu’s broom this one has shorter bristles and doesn’t flex as nicely, but the man is really sweeping. After two minutes (film time) a phone rings and another man, who has been doing something behind the bar answers. The scene cuts to him and we hear his conversation. After listening in for a minute or so, we are again shown the man sweeping and by now he has swept all the dirt into a neat pile. There is a sense of dignity about the sweeping. It’s a job worth doing, and worth doing well.

The floor is now clean, the dishes have been washed, the kitchen bench wiped and through this process of cleaning and finding out about cleaning and dirt a softening has occurred. Cleaning and dirt are one part of everyday life where the ever changing relationships between one thing and another, one situation and another, one intention and another are woven together in a continuous cycle of change and movement, and one where context is everything. The reasons for cleaning range from the practical – to make space, to maintain sanity and hygiene – through to the emotional, purely aesthetic and spiritual. I can clean to express love but as I progress through from being dutiful and caring I arrive at pointlessness and drudgery and from there the full emotional landscape from anger and frustration through to reassurance, acceptance and calm is revealed. Some cleaning is appropriate, while some is not. Some is a performance, while some go unnoticed. Some is real, some is pretend. It can be taken seriously, or not. It’s private but can also be public. As I clean I can be self-absorbed and self-aware focusing on my individual embodied experience of cleaning, but that doesn’t mean I’m not unaware of social and economic aspects and my connection with a great number of other people. As all these aspects become intertwined and seem to fold in on themselves and even contradict one another, the actual fluidity of categories like clean and dirty, necessary and unnecessary becomes apparent. Frustratingly, but realistically, the answer to many questions is, ‘…well, it depends’. I still get angry with the vacuum cleaner and I still rage occasionally about ‘Why me?’ but the knowledge that there will always be dirt and there will always be something to clean locates what I am doing in a much larger picture, a cyclical one of repeated actions, care and neglect. And there is also the option of not cleaning. I could just talk about it. I could make art about it. I could write about it. Strangely enough, the knowledge that there is plenty of dirt helps me to relax. As I write these final words I tune in to the reassuring sound of the washing machine as it chugs and whooshes through its cycle. Someone else is doing the cleaning for me, at least for the moment, at least until it’s time to hang the washing up.

References

- The Door, dir. by István Szabó (FilmArt Kft. 2012).

- Collins English Dictionary, (Harper Collins, 2014 <https://www.thefreedictionary.com/sanitary> [accessed 10 February 2023].

- Kathleen Norris, The Quotidian Mysteries : Laundry, Liturgy and “Women's Work”, (New Jersey, Mahwah: Paulist Press, 1998), p. 75.

- Yuriko Saito, Everyday Aesthetics and World-Making, online video presentation, YouTube, 2013 <https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ktwTiUl_fEQ> [accessed 19 January 2017].

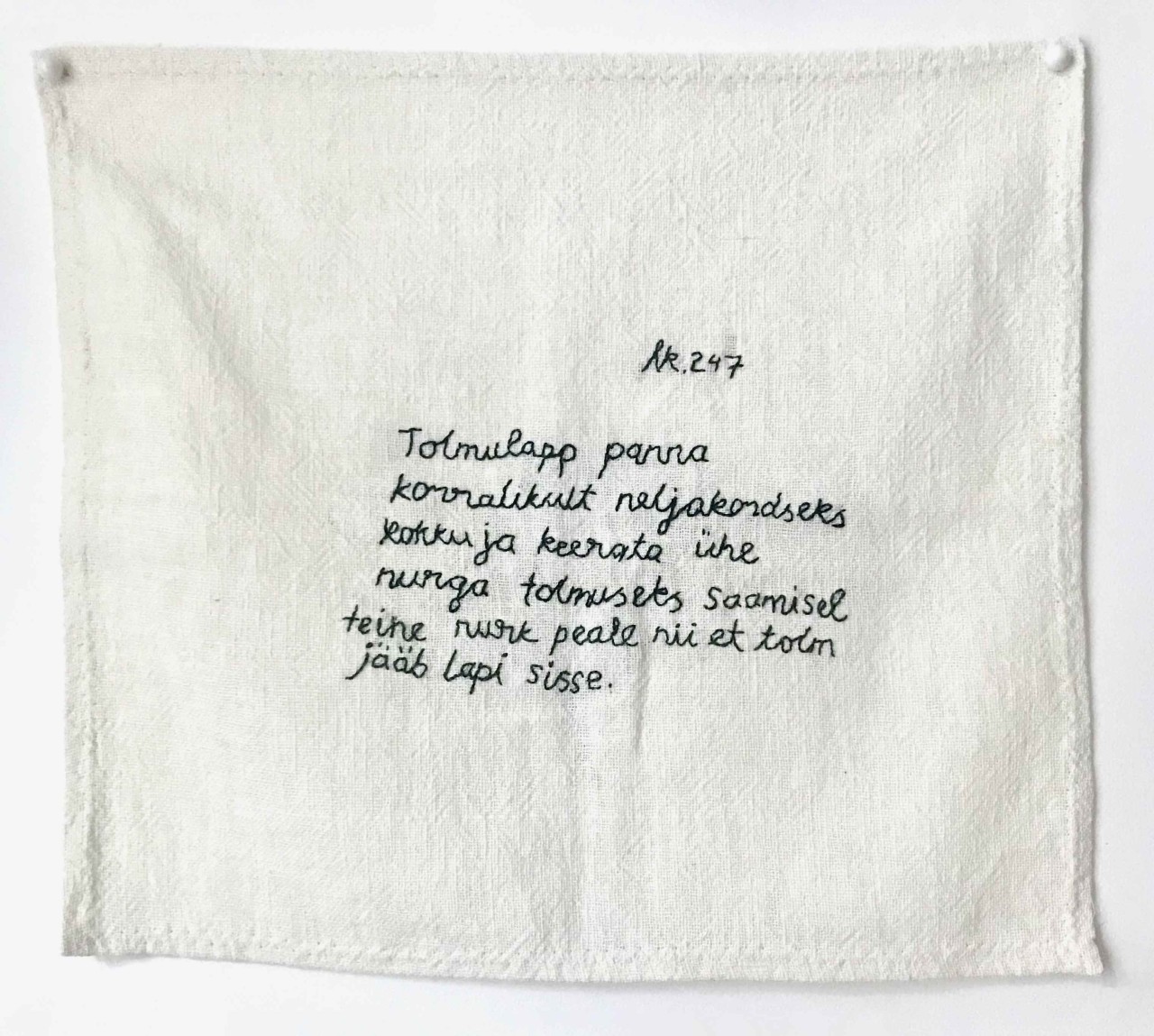

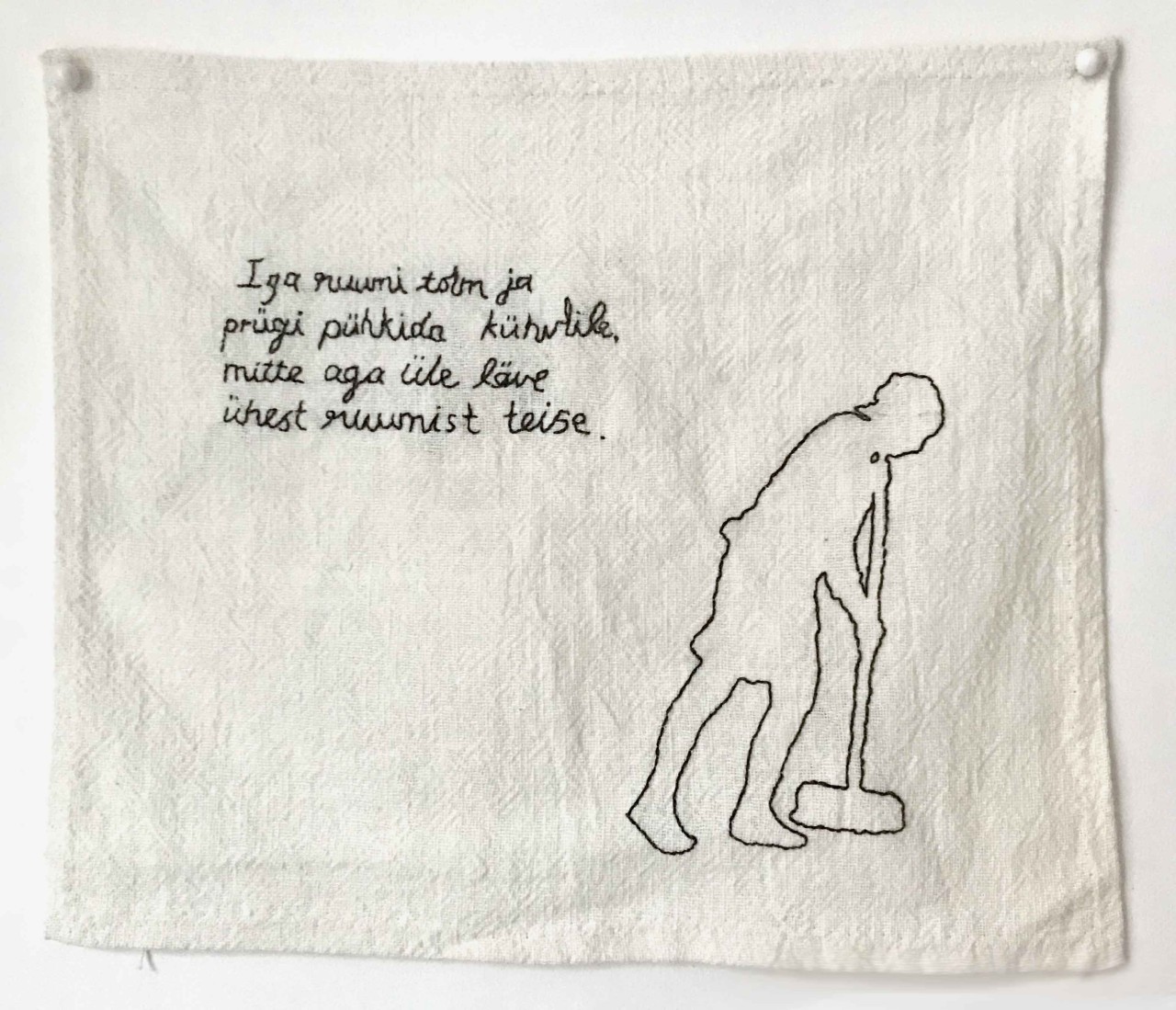

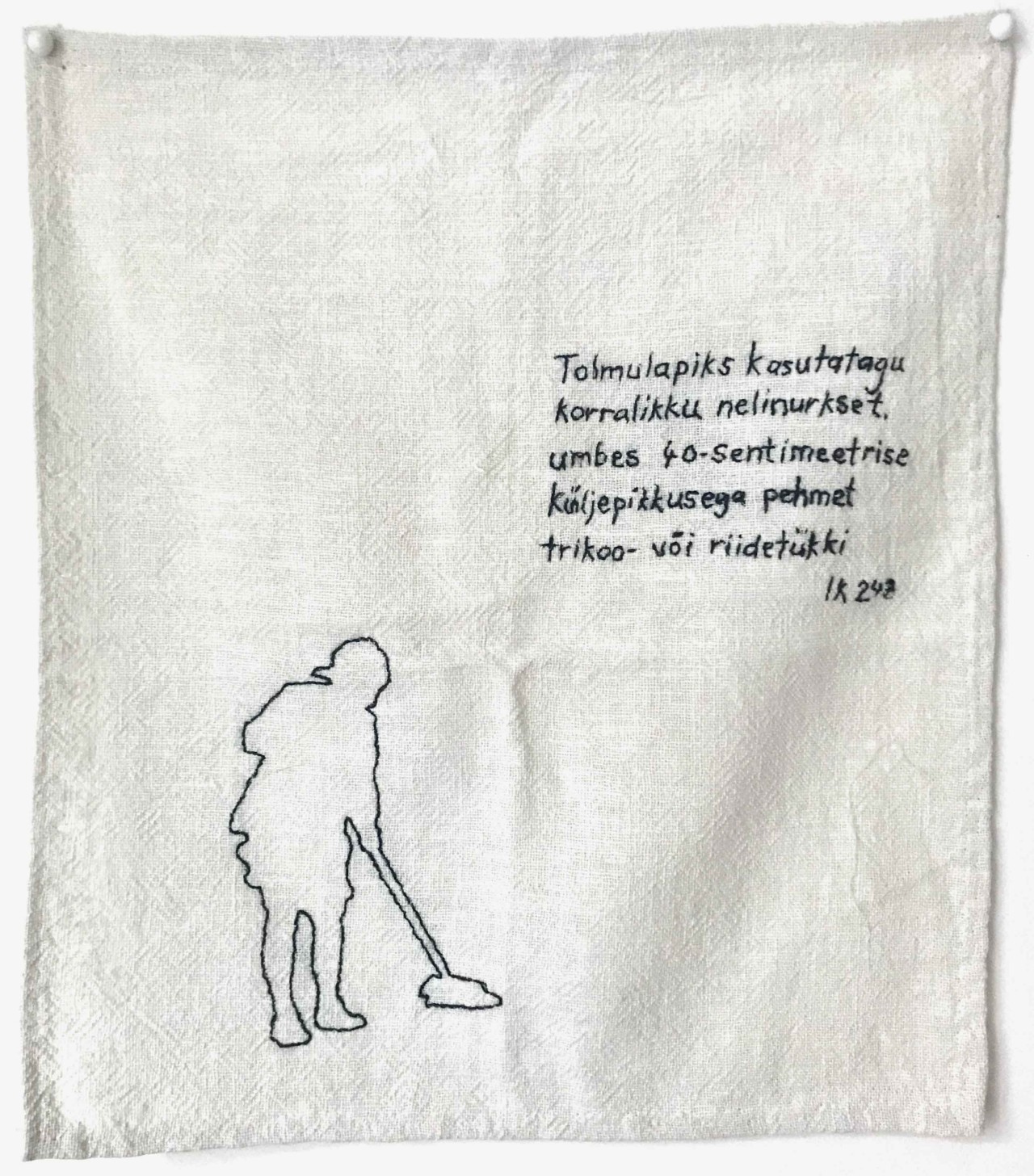

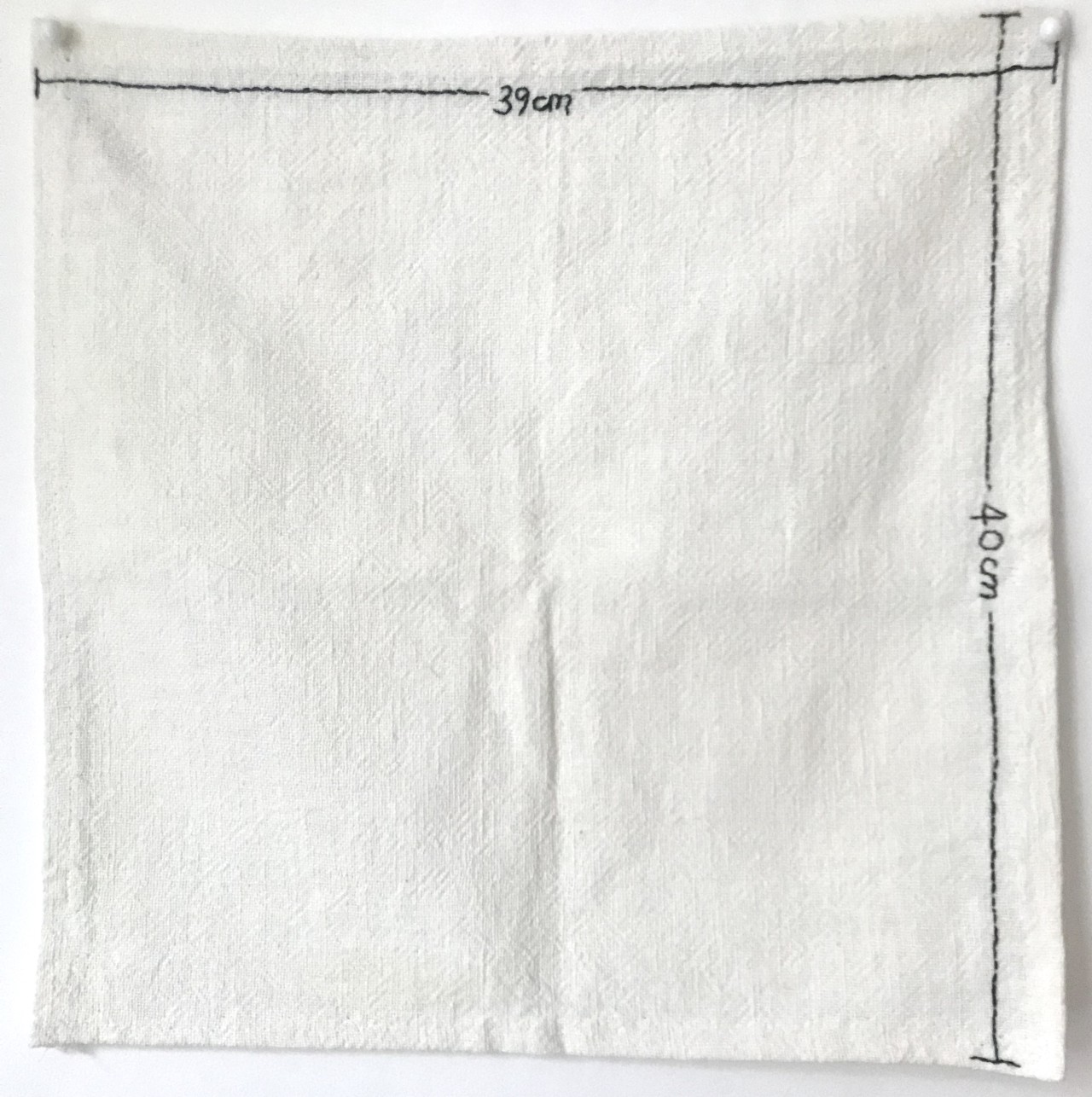

- L. Lints, D. Luitva, I, Savi [et al], Perenaise käsiraamat (Tallinn: Valgus, 1968), p. 247.

- L. Lints, D. Luitva, I, Savi [et al], p. 247.

- L. Lints, D. Luitva, I, Savi [et al], p. 247.

- Simone de Beauvoir, The Second Sex. trans. by H. M. Parshley (London: Vintage Books, 1997 [1949]), p. 470.

- Françoise Vergès, A Decolonial Feminism, trans. by Ashley J. Bohrer with the author (London: Pluto Press, 2021), p. vi.

- Françoise Vergès, p. 2.

- Cecilia Vallejos & Matthijs de Bruijne, Take a Risk and Explore: The Visualisation of the Dutch Cleaners’ Movement (Yes & No, 2017) <https://www.bakonline.org/person/matthijs-de-bruijne/> [accessed 12 February 2023].

- Meg Luxton, More than a Labour of Love. Three Generations of Women’s Work in the Home, (Toronto: Women’s Educational Press, 1980), p. 11.

- Meg Luxton, p. 12.

- David Foster Wallace, ‘Essay A supposedly fun thing I’ll never do again’ in A supposedly fun thing I’ll never do again, (London: Hachette Digital e-book, 1997).

- Foster Wallace, p. 272.

- Foster Wallace, p. 273.

- The Simpson’s Movie, dir. by David Silverman (Twentieth Century Fox, 2007).

- Elizabeth Jolley, Central Mischief (Australia: Viking Books, 1992) pp. 9–10.

- Ilja and Emilia Kabakov, The Short Man <http://www.kabakov.net/installations/2019/9/15/the-short-man> [accessed 12 February 2023].

- Tokyo Story, dir. by Yasujirō Ozu (Shochiku, 1953).

- Mary Douglas, Purity and Danger (London: Routledge, 2002 [1966]), p 36.

- Asad Raza, Absorption, 2019, Carriage Works, Sydney.

- From a spoken conversation with Fideelia-Signe Roots who wrote about Elmina Otsman in her PhD dissertation “Naine kui kangelane / Woman as a hero”, (Tallinn: Eesti Kunstiakadeemia, 2017).

- Part of the exhibition Living Space, curated by Katrin Repnau and Bernabette Pilli, Red Gallery, Melbourne, 2018.

- Shoukei Matsumoto, A Monk’s Guide to a Clean House and Mind, trans, by Ian Samhammer, (UK: Penguin Books, 2011 [2018]) p. 53.

- Haruki Murakami, IQ84, (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2011), p. 981.

- Twin Peaks: The Return, dir. by David Lynch (Showtime, 2017).