Published on 31.12.2023

The art collective Knock! Knock! Books (KKB) was established in 2016 by graphic designers Else Lagerspetz and Loore Viires. Using fictions, graphic design, illustration and a variety of performative practices as their tools, KKB aims to research and analyse pop-cultural phenomena. Among others, KKB has collaborated with publishers such as Lugemik and Colorama and presented their work in exhibitions and at book fairs. So far, KKB has published independently or collaboratively six publications and written for various art publications.

Most of the potential projects and book ideas by Knock! Knock! Books are suspended in a sense – they are like melodies, titles, names for fictional characters and concepts that have formed during moments we have spent together and that will be contextually fleshed out only after a time. The background will form in a process of reflection, from references that emerge from the depths of memory, examples accumulated over the years and eventually, when the project is beginning to take shape and move towards a more concrete expression, methodical research. And so, we sometimes grab onto a rather specific commission and expand the given theme until we can just about fit it with an idea we’ve grown keen on.

We began Knock! Knock! Books in 2015 and defined it from the very beginning as a “fictional publisher”: we mostly wrote fiction around non-existing books, their design and their place in cultural history. Over the years and as new projects came about, the initial concept of Knock! Knock! Books began to break up a little bit and we started to prioritise different ways of writing: blurring the line between fact and fiction, stitching fiction with fertile (pop)cultural references and experimentation with genres and styles.

While our first book, Notes, Memories and Fictional Accounts of Published Works1 was rather neutral and catalogue-like in its tone, the next couple of publications – Signals from the Periphery2, made for an exhibition of the same title at the Tallinn Art Hall and Secrets of Shelves3, created during the Books on Books workshop in Berlin – we very consciously imitated the language used in certain periodicals. Päringuraamat (Book of Inquiries), published in 2019 to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the art books department at the National Library of Estonia was written in an exaggerated and pompous style. The text is full of references to antique mythology, the language is ridiculously romantic, the stories we heard during our research are written into a heroic tale of the adventures of a library visitor with dubious motives. Also, the 2022 Kirjavõlglane (Type Debtor), published as part of the exhibition A Book Designer’s Studio. Jüri Kaarma and Late Soviet Graphic Design, we experimented with fiction – stories of Soviet publishing and book production are written into a thriller about a Renaissance era curse put on book printers. At the same time, we try to shed light on forgotten processes and technologies with the story.

Since our books often need an external impulse to be realised, we have decided to use this article as an opportunity to develop one of our partially outlined ideas further. On the one hand, this is motivated simply by our own selfish desire to take the time to create another publication alongside other jobs, on the other, by the hope that by showing how we write, we are able to exemplify the process on research and (knowledge) production that is idiosyncratic to Knock! Knock! Books, which we are very rarely able to apply in our other projects.

A couple summers ago, we were having a nice post-sauna evening at a summer cottage in Lahemaa. We were playing Chinese chequers, a game played on a hexagonal board, and eagerly commenting on each move. Jumping over each other’s pieces, one of us happened right on the path the other one had planned to take. Jokingly, we started to describe this move as “blokbololok”, which developed into a song about “the little Plok Bololok”, an active child with a strange name, something like a character out of an Astrid Lindgren book.

The Plok Bololok book series introduces a busy and maybe slightly grumpy child, who has all kinds of adventures in a big hectic city. Plok wanders among tower blocks, searches for coins around a kiosk to buy chewing gum that comes with little sheets of temporary tattoos, and picks out their favourite graffiti on a fence next to the kindergarten. As part of their adventures, Plok rides in a taxi, takes public transport, travels on foot and once even manages to get picked up by a cargo bike. All these activities are driven by the child’s resourcefulness and curiosity. Read the book and find out what annoys Plok in the city!

Previously published in the series:

Plok Bololok in the Big City

Plok Bololok and Fast Cars

Plok Bololok is Late Again

Plok Bololok Goes to the Countryside

Plok Bololok is Really Mad

Plok Bololokand the Artificial Sun

Seven years ago, we were working as teachers at two schools in Tallinn. The schools were in the opposite parts of the city and we discovered ourselves outside our usual rhythms: early in the morning, often stuck in crowded public transport that also tended to arrive late or not at all. In moments like these we sent each other messages on how the trolleybus was late again, to which the other replied with a quick red car emoji or a slightly passive aggressive “beep beep” – a frustrated reaction to the traffic in the city. Perhaps due to that experience and the way we kept on using “beep beep” ever since, we later imagined that Plok Bololok’s stories could focus on artificial sounds and the chaos of traffic in the urban environment.

The children’s books and animations we use to exemplify and describe the Plok Bololok books are above all the kind we have had an experience with – we either vividly remember these from our childhood or they resemble the kind we have read and seen when looking after our little relatives. When creating the world of Plok Bololok, we trust above all the childlike sensibility evoked by the examples we remember so well.

Traffic-themed books and animations for children are optimistic and engaging, making getting around in the city almost a fun game. The joyful world they envision does not really reflect the real world – you only encounter cars enthusiastically beeping their horn in wedding processions, in fact, we mostly hear that in traffic jams or in tense traffic, where the horn is used either as a warning or a sign of frustration. The ding-ding of the tram is also similar in the sense that unless it is directed towards a pedestrian crossing the street in the wrong place or at the wrong time, it is a lonely and melancholic sound chiming for the driver of another passing tram.

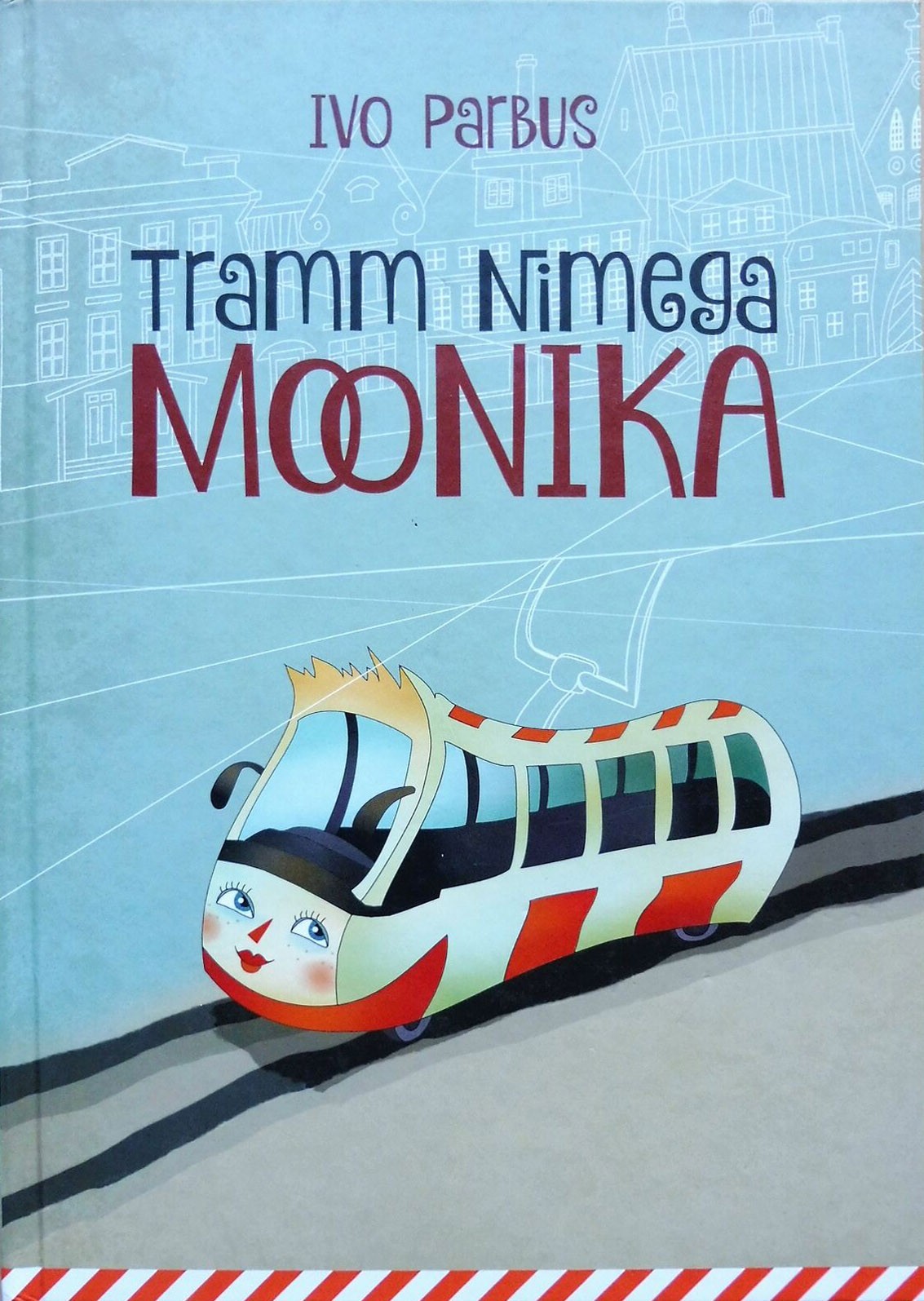

In the 2016 children’s book Tramm Nimega Moonika (Tram Named Moonika), published by the Tallinn Transport Department to mark the arrival of a new vehicle, a tram wearing mascara and lipstick runs around Tallinn as if on a joyride, encountering other friendly trams and discussing the pleasure of hauling people around:

In the extremely popular lullaby Mina Ei Taha Veel Magama Jääda (I do not want to go to sleep yet) written by Heino Jürisalu and Juhan Saar in the 1960s for a children’s radio programme, the main character hears cars passing by while trying to fall asleep, a sound utterly familiar to everyone living in the city:

Cars are not sleeping and they call to me

beep-beep-beep, beep-beep, beep

outside my window.

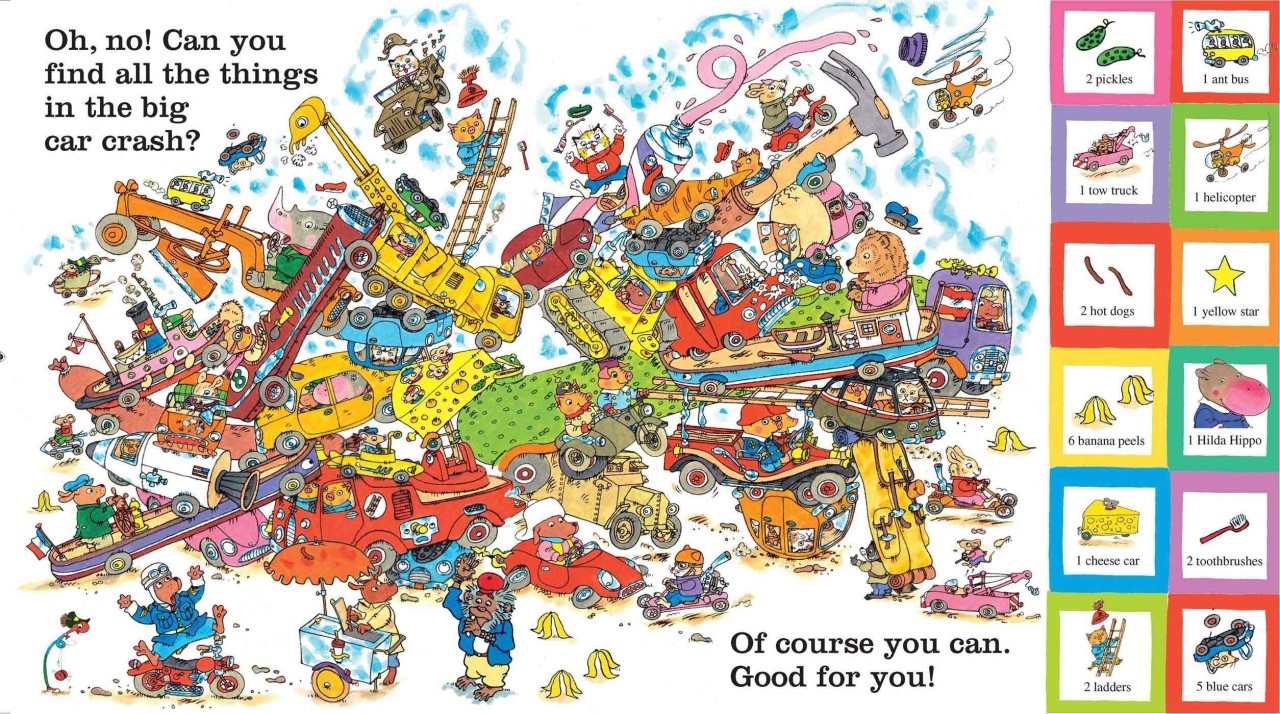

Alongside these kinds of romantic urban stories, the Estonian children’s classic Rongisõit (Train ride) by Ellen Niit and the song Sile Tee (Smooth ride) sound almost dramatic. The first describes a serious train accident, the other includes physical movements simulating the driver’s fall into a hole. Similar contradictions can also be found in the work of the American children’s writer and illustrator Richard Scarry, whose cute animals adventuring in Busytown try to escape traffic tickets or crash their tractor due to a lack of driving skills. Scarry’s seek-and-find type book4 asks the child to find different items among a large amount of vegetables spilled in a big traffic accident:

We often work through the central idea of a book in multiple versions and experiment with different possible forms until we actually publish it or decide to keep it as a private joke between us. In 2019, we were invited to play a dj-set at TOPS bar on Soo tänav as part of their event series Femme Fatale. Instead of playing our favourite songs, we decided to use the opportunity to develop the Plok Bololok project and compiled a set of traffic-themed tracks. The playlist5 consisted of different types of music, the common thread being thematic (or sonic) references to vehicles and to the urban environment. We started off with the long foghorn sounds of the 1956 song The Ferryboat Serenade by The Andrews Sisters, other traffic sounds were sampled from tracks such as Billy Ocean’s disco hit Get Outta My Dreams, Get Into My Car, The Art of Noise’s synth track Close (To the Edit), where the samples of motor sounds are collaged into a catchy beat. In the chorus of Bad Girls by the disco legend Donna Summer, we hear the repetition of “Toot toot, hey, beep beep”.6

There was a period, where we didn’t think much about Plok Bololok but we were still attentive towards any kind of content that could relate to the character. We both follow the popular Estonian online account @Mitte_tallinn, commenting on the traffic culture in Tallinn, the city’s traffic management system and urban landscaping decisions. They create photo collages that highlight the shortcomings in the city and visualise potential solutions to create a more human-centred urban environment. Their content has been eye-opening as a pedestrian and as a cyclist in noticing uncomfortable traffic routes and was probably the reason the thought of a small child wandering around the city evoked negative emotions and a sense of danger rather than the excitement we know from children’s books.

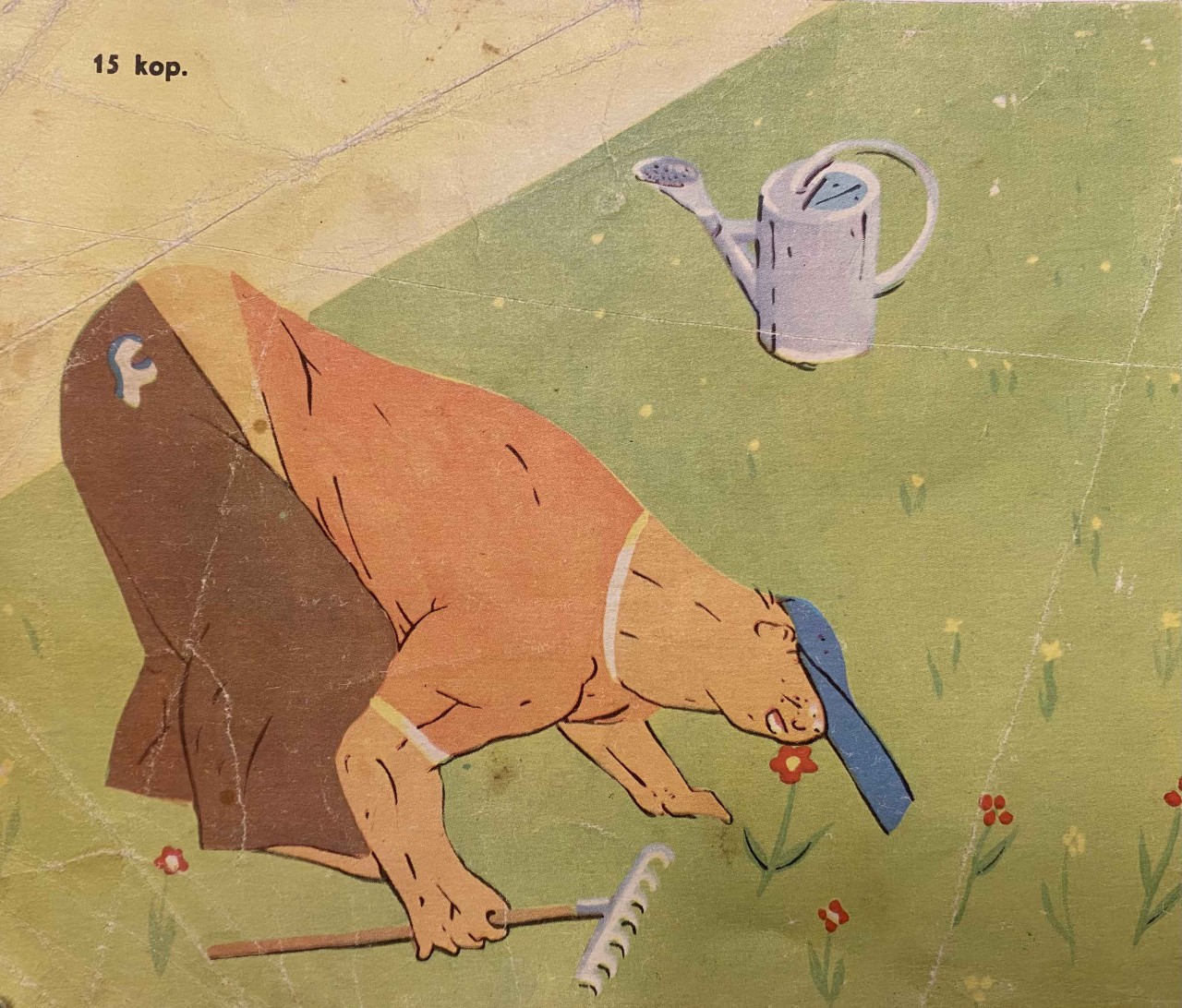

In the animated film Rüblik (Rascal)7 by Rein Raamat and the book8 based on the animation, the main character, little Jaan goes to school and goes about his daily activities in a child-like haste and thoughtlessness, so among other things, on his way to and from school, he runs through a patch of grass the groundskeeper is carefully maintaining. One day, a sign is put up next to the patch, warning everyone that whoever runs through it, is a little piggy. Jaan does not care, of course, and happily traipses through the patch again. In the evening, the boy turns into a little piggy and almost having lost any hope of ever becoming a human again, he takes a walk at night. He is seen by the groundskeeper, who makes a new sign, saying that whoever walks the designated walkway is Jaan, which then turns Jaan into a boy again.

From a contemporary point of view, the story seems quite controversial. On the one hand, we consider well-maintained and designed landscaping a part of a good quality living environment, on the other, we also use terms such as desire paths to indicate spontaneous paths created by foot traffic that are often used in contemporary cities to plan pedestrian’s trajectories well before roads are constructed. After all, an ideal urban environment does not threaten people who just want to be more comfortable with punishment, but rather takes their habits into account.

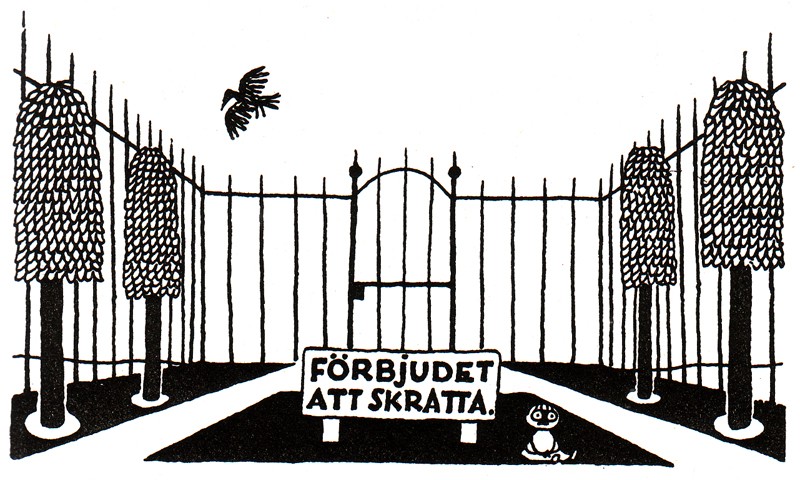

In Tove Jansson’s book Moominsummer Madness,9 the fate of the signs that try to regulate behaviour is completely different. Snufkin, a pensive adventurer, who does not want to follow social rules goes to a park full of prohibiting signs. Together with a group of children, Snufkin digs up the signs to allow everyone to enjoy the public space.

From time to time, we made attempts to develop the character and the setting of Plok Bololok further. For example, once Loore suggested we write about Plok Bololok (the name has also taken different forms over the years) taking turns, a couple of sentences at a time.

It was getting dark, Blok Pololok was strolling home and muttered: “Again. Again! This is the fifth, no, the sixth time in the last two weeks! “You go ahead and take the bus and make sure you sit in the seat right behind the driver,” they always say but what do they know! How can I make sure to sit in that seat when the damn bus never comes!?” Blok grumpily kicked a pebble on the street but instead of the dumb pebble, her own foot got hurt. Jumping up and down on her better foot, Blok cried out all the curse words she knew.

In this random and slow manner, we reminded each other of Plok Bololok, sometimes in connection to an article, a song or a character we encountered.

In 2021, Else was preparing to graduate from her Master’s studies at Aalto University. Her thesis was on independent publishing and to supplement it, we created an updated, 2021 catalogue for Knock! Knock! Books, presenting our real and fictional publications. Among the soon-to-be-published books, we described a book entitled Plok Bololok. The introduction says:

The publication introduces Plok Bololok, a little rascal living in an anonymous Eastern European town. This character and her adventures are a composite of 20th century children’s books, animations and other media from the area. Playing with the visual and thematic tropes of such children’s stories, the actual focus of the book is on the urban setting in which the events take place. The city environment is analysed through the many sensory layers of the urban experience: the noise, the dust, the smell. The poor planning and chaotic social relations of new areas of tower blocks evoke stress – but also embody a sense of familiarity and wistfulness.

The richly illustrated book comes with an LP featuring a selection of transportation-themed pop songs as a separate exploration of the themes discussed in the publication.

The description also states that it is a large-format, 30 x 30 cm and 144-page publication. The cover includes an abstracted image of the Väike-Õismäe district in Tallinn, almost resembling a sidewalk chalk drawing.

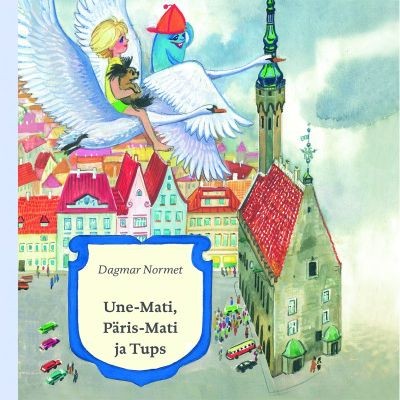

The Plok Bololok books are centred around the main character and urban environment – not necessarily a kind urban landscape of Tallinn’s Old Town like we encounter in Sammeli, Epp ja Mina10 (Sammeli, Epp and Me) by Ilon Wikland, where little friends (and a dog) eat chocolate sweets in a café, or the capital as seen in the illustrations by Siima Škopf for Dagmar Normet’s book Une-Mati, Päris-Mati ja Tups11 (The Sandman, Mati and Tups) admired by little friends (and a dog) from a bird’s-eye view.

The surroundings little Plok confronts and socialises in are grey, muddy and bland, cars toot their horns in a bad mood and trams perhaps do not even go into the outskirts of the city. The brave and stubborn Plok gets mad at the loud traffic and the wind sweeping through the city – and so Plok invents small ways to feel better in a poorly planned city. For example, Plok asks a friend and their grandmother to help her create a footpath between a sweets kiosk and a bus stop to avoid crossing a big and dangerous intersection. The urban environment Plok lives in is simultaneously frighteningly vast and unfriendly but full of little secret corners for a child, familiar shopkeepers and friendly animals.

Our ideas about what the Plok Bololok stories as physical books could look like have changed over time. Initially, we imagined a rather text-focused literary publication, similar to the works of Astrid Lindgren or Estonian children’s books; after a while Plok’s story became increasingly laconic, image-centred books for younger children. We imagined the visuals of the book being similar to Czech animations we had seen as children or in the style of posters depicting Soviet work heroes, extensively using the collage technique and brownish-grey colour scheme. Planning the picture book further, we decided it should be a collection of independent scenes that cover the whole spread and allow for a poster-like combination of text and illustrating image. For us, the Plok Bololok book would be an opportunity to experiment with another style of storytelling – instead of a journalistic portrait or a sentimental story, we’d go for a clearly worded children’s book-like narrator and illustration as the vehicle for the narrative.

AT NIGHT PLOK LIES IN BED, SLEEPLESS. SHE JUST CAN’T FALL ASLEEP. PLOK SHUTS HER EYES AS TIGHT AS SHE CAN, IMAGINING A BIG ROAD. PLOK STANDS BY THE ROAD AND WAITS FOR THE LIGHT TO TURN GREEN. SHE LOUDLY COUNTS THE NUMBERS ON THE TRAFFIC LIGHT – 52, 51, 50, 49… AND ALREADY SHE IS FAST ASLEEP.

Stanislaw Lem, mainly known as a science fiction writer, has written a couple of fascinating books on non-existent books. A Perfect Vacuum12 is a collection of literary critiques on non-existent books, Imaginary Magnitude13 is a compilation of introductions to non-existent works. Basically, Lem uses these short forms to sketch out works he has no intention of writing but he still manages to create vivid images for the reader. In the introduction to the book, Lem says that these texts are “…announcements of sins from which I shall abstain.”14 Let’s see, if Plok Bololok becomes another one of our literary sins. But if not, storytelling may, after all, be made up of fragments: noted down references, sounds, illustrations, the various expressions of the same idea. At least, in the world of Knock! Knock! Books, books can remain unwritten, their physical existence is secondary.

References

- Lugemik, 2016.

- Eesti Kunstiakadeemia Kirjastus, 2017.

- Colorama, 2017.

- “Cars and Trucks and Things That Go”, Golden Books, 1998.

- Recording of the traffic-playlist on SoundCloud: https://soundcloud.com/user-614380643/knock-knock-books-tops-11072019

- The singer Taana Gardner describes in an interview with The Guardian how in the 1980s in the popular disco club Paradise Garage, the resident dj, Larry Levan induced a trance-like state of mind among the visitors by looping Donna Summer’s lyrics “Toot toot, hey, beep beep” for half an hour.

- Tallinnfilm, 1975.

- Perioodika, 1979.

- e.k Tiritamm, 1995.

- Huma, 1998.

- Eesti Raamat, 1979.

- Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, 1985.

- Harvest Books, 1985.

- p 3.