Published on 14.06.2024

Priit Tohver is the head of the Sustainable Development Department at the North Estonia Medical Centre. The department’s activities range from strategic planning to research and development, as well as quality management. Tohver leads a team whose goal is to build a learning organisation in the largest acute care hospital in Estonia. With a background in medicine, Tohver previously worked as an e-services innovation advisor at the Ministry of Social Affairs, where he was responsible for promoting data-driven decision-making and healthcare innovation.

Ruth-Helene Melioranski is the Dean of the Design Faculty at the Estonian Academy of Arts. She has a background in design research, practice and education, focusing on exploring how design can tackle societal challenges. She conceptualises new and emerging design practices in higher educational and professional contexts through her research-through-design projects. In her professional practice, she leads several strategic, service and co-design projects to help partners envision their future possibilities and build scenarios in healthcare and well-being.

Daniel Kotsjuba is a designer, lecturer and head of the Social Design MA programme at the Estonian Academy of Arts. For five years he worked for the Public Sector Innovation Team in the Estonian Government Office, promoting collaboration-based public governance that relies on design methods. He has been in charge of various design projects in the Estonian public sector, provided design-related training and fostered networking activities.

Over the past decade and more, the North Estonia Medical Centre (hereinafter referred as in NEMC) and the field of healthcare in general have consistently collaborated with designers, while also welcoming design-based thinking. This can be seen by the various collaborative projects and the creation of positions for in-house service designers within the departments of research and development. Three practitioners directly involved in healthcare improvement, each of them approaching it from different perspectives – Priit Tohver, Ruth-Helene Melioranski and Daniel Kotsjuba – reflect on the experiences gained so far, while also discussing recent assumptions and expectations for future collaborations. The discussion is moderated by Daniel Kotsjuba.

Daniel Kotsjuba: What has been the impact of applying design to the Estonian healthcare system in general and specifically to NEMC?

Priit Tohver: The past decade has indeed been a time when collaboration between various hospitals and universities teaching design has been effective. Reflecting on when and where design thinking began to enter the healthcare sector on a global scale, I would mention the 1980s when a group of doctors in the United States and Canada introduced the concept of quality improvement in healthcare. This was the school that had become very strong around that time and had influenced me the most when I took over the quality control service at NEMC. No one talks about quality assurance anymore; everyone talks about quality improvement. When I started working with my sister service – the research and development service – they told me about service design. When comparing the activities of quality improvement and service designers, then they use more or less the same tools. Their tasks include similar observations, process mapping, interviews, patient-centred thinking – only the activities have slightly different names. Now, when reframing the question of what the continuous pursuit of improvement has actually brought to healthcare, it has most notably resulted in a better work environment for healthcare professionals. Healthcare doesn’t have to be static, and we can do things differently. I believe we are very fortunate in Estonia to have universities that have helped bring design thinking into hospitals. This, in turn, has included healthcare professionals in these projects and shown that things can indeed be improved, that their ideas matter, and that with their ideas it is actually possible to make their own work environment and the patient experience better.

Unfortunately, many projects tend to remain in the project phase, and don’t end up being implemented. There are many factors that explain why projects often fail to be carried out, but I think it’s just a matter of time before something changes. The experience alone, that you have taken the time to think about how we work and whether we will continue to work in the same way for the next 20 or 30 years, is valuable. If the same people ever become department heads they will be even more awesome department heads because they see that changes are possible.

Ruth-Helene Melioranski: We have a curriculum called Design and Technology Futures, where we encourage students to think ahead into the future, and since the technological aspect is also emphasised then the proposed solutions are usually quite extensive IT developments. But we also think through how processes could work, and quite many smaller parts of the process have been put into use right away. I remember that in 2015–2016 we held a week-long design spring in collaboration with the former day surgery department who were highly motivated to work with us. At first, there was hope that students would redesign the so-called boring white waiting room, but as is typical in service design, the patient journey was still considered to be the priority. One aspect that emerged during the interviews was that these people are actually just waiting there, and the white space becomes emphasised precisely because people are put there to spend time. One move suggested by the students was learning to walk with crutches under the guidance of a physiotherapist. Previously, this activity took place after surgery, but now it was moved to the pre-op waiting time. On the one hand, this helped make use of the waiting time, and on the other hand, the person was not nervously thinking only about the operation; besides, they are healthier and physically more capable of participating in learning. And by the end of the course, the physiotherapist was then already involved in the patient’s journey before the surgery.

PT: When talking specifically about changing something, then the most valuable changes are those where, simply through questioning and careful observation, we consider why we are doing things this way and not another way, or in a slightly different order. The fact that the physiotherapist works with their patients already before the surgery is a very good example because it is in line with another change that is taking place in the field of surgery. We are no longer talking about rehabilitation, but prehabilitation. So in fact we start by building up a person before the surgery, so that they go into the operation in better condition and recover faster. But what if the sequence of steps were different, would anything change, would anything improve? In my opinion, these are cool questions, and we need to learn to ask these questions more often in our daily work.

Recently, we conducted a fruitful observation in the operating room. In the operating centre, operating room nurses are highly valued. It’s not just the doctors who decide; we try to get as many people involved in the system to talk to each other in the same room. Talking to each other is not only beneficial because better ideas emerge, but it also reduces the hierarchy a bit, which actually improves a whole range of things, especially when it comes to patient safety. If a doctor makes a mistake and a nurse notices it, it only becomes harmful to the patient if the nurse doesn’t dare to speak up. And usually, they don’t dare to speak up when there is a very strict hierarchy. But if everyone is treated equally, there is a greater likelihood that each other’s work will be checked in terms of patient safety. And in my opinion, design projects that bring different parties together in one room are very important and valuable, especially from the perspective of shaping such a culture.

DK: I can bring an example that particularly highlights the value offered by design and emphasises the need to come down from the ivory tower in order to collectively address concerns – a collaborative project with an oncology clinic to analyse the patient journey. One moment that I clearly remember was when, as a result of the study, we visualised the critical aspects and success events in various stages of this journey to the representatives of the clinic; and this led to gaining their full attention. It became clear that the problems do not lie within a single institution or individual but that the entire patient journey needs careful consideration. Concerns arise long before they arrive in the hospital because patients often require support in the earlier stages. New questions arise: How can we provide support to a person who is not directly within my area of responsibility? There are also questions that extend beyond a particular healthcare centre and encompass the entire organisation of healthcare and social services, including family doctors, local government employees, issues about the movement and sharing of data, and so on. Therefore, there is no other option but to come together to find solutions.

R-HM: The non-hierarchical approach as well as bringing all parties together were also at the heart of one joint curriculum course. We focused on co-design and its implementation. We taught the participants how to use visual thinking to help them express themselves differently. On the one hand, it is important for people to have the vocabulary to express their thoughts. On the other hand, people may start to censor themselves if their boss is present, even in a relaxed atmosphere. Now, when people are asked to create a journey using mood pictures, where they describe their feelings and emotions, then the discussion goes to a completely different level. People don’t control their self-expression as much because visual tools offer new ways of expression.

The central idea of co-design is indeed to bring together people from different backgrounds. Our design teams and new curricula, including the joint curricula and the Master’s programme in social design, welcome students from diverse backgrounds. There are both designers and individuals who already have acquired a Master’s degree and come to study design as a new field. The goal is not only to improve one’s work but also to acquire new tools and see things differently. One way to achieve this is to bring various people together and help them understand different perspectives on the same topic.

DK: But who are the different parties in a healthcare institution? What does a healthcare institution look like from the inside?

PT: There are numerous parties in a clinic, starting with the professional groups that include doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, midwives, speech therapists, and others. In addition, there are support specialists, such as infrastructure engineers, biomedical engineers, catering and wardrobe staff, caregivers, and cleaning service personnel. The maintenance department at the clinic is like a separate hospital ward where services are outsourced. It is also important to take these differences into account.

In addition to professional groups, the clinic has management levels. Heads of departments, units and teams form the heads of first-level management. The head of a centre is at a higher level – that person is usually the head of a certain medical field, such as an orthopedist, and thus also the head of an orthopaedic centre. The clinic also has other specialist centres, such as the surgery and specialist care centres. In addition, there are support services that are not limited to one clinic, including members of the clinic boards that normally tend to be small.

When planning projects in healthcare, it’s essential to consider all parties. Depending on the project, it can be necessary to involve IT specialists, infrastructure specialists, cybersecurity experts, security personnel, etc. The North Estonia Medical Centre encompasses nearly all professions imaginable, including service designers.

R-HM: Besides the journey maps, the mapping of various parties is one of the tools that students use in service design projects. This helps visualise how each party is related to the project topic and highlights their interconnections. Returning to the day surgery project, I remember that during the mid-term review, the students printed out the journey map and the map of involved parties. It was like a giant system that reflected the patient’s entire journey from their arrival at the hospital in the morning to leaving the hospital. The maps made it possible to see how each change affects the entire system. To paraphrase clinicians from that moment, this tool helped explain why some changes cannot be made. It provided them with a lot of clarity on how they operate in general.

PT: I recognise such thinking, and I wouldn’t want to agree that involving many people prevents changes from being implemented. However, when you start digging deeper, practically every change requires a wide range of people. Even if it’s a change that only affects a few types of positions, you may need to involve many representatives of those positions to get them interested in participating. Unfortunately, progress cannot always be made with just small adjustments; sometimes more systemic changes are needed. In those cases, the question is how we can start small to demonstrate the success of the proposed solution. People are more likely to embrace changes that have been successfully demonstrated in a smaller circle, showing that the solution is effective.

In some cases, society in a wider sense can also be considered a stakeholder. Many hospital emergency departments receive terminal patients towards the very end of their life. This is inhumane from the patient’s perspective and an irresponsible use of healthcare resources. In reality, there is nothing that can be done for these patients. However, changing this situation so that patients don’t have to spend the last minutes of their lives in an ER room requires a significant shift in societal thinking. Which is not to say that change should not be attempted.

R-HM: On the one hand, it’s certainly a culture-related question regarding how ready we are as a society to confront death. But on the other hand, it also shows that as ordinary individuals we simply don’t cope well with such situations, or we haven’t acquired the necessary skills or received even basic counselling.

DK: Priit, what’s your professional view of the possible approaches to initiating and managing changes in healthcare?

PT: I think the clearest and most logical change management theory for me is John Kotter’s Eight Step Change Model, and we try to apply it in healthcare as well. The most important thing is that everyone first understands the problem and that there is a common desire for change. If only a small circle of people are passionate about an issue, then change won’t happen. In the context of design projects, when we start unravelling the problem, there should already be a coalition of people who not only recognise the problem but also have the power to change it. So, the first step towards change – raising awareness and finding allies – is often the most difficult one. Enthusiasts start moving without actually having the necessary coalition to implement the change.

From there we are trying to move forward in small steps, and there is a very important measurement component that has actually improved. Often this is left undone because it feels like there’s not enough time and we’ve already made a change. We’re trying to implement more so that there’s more impact evaluation in improvement projects. And from there, it is possible to move on with increasingly larger steps. In health care quality improvement, we talk about a PDSA cycle – plan, do, study and act based on what you have learned.

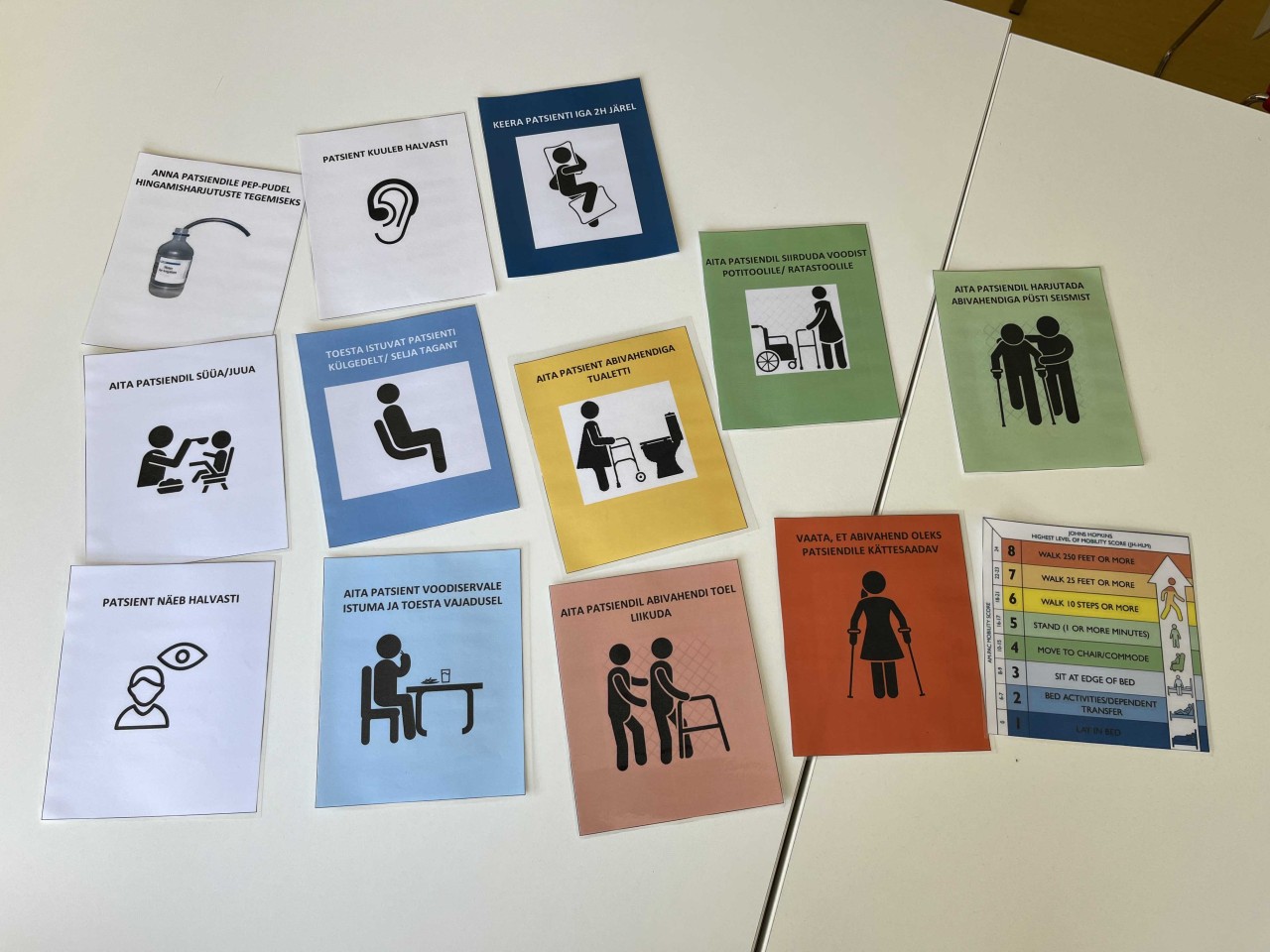

We had a great example recently, which actually started with physiotherapists. They had a problem with patients with bedsores and they made a very simple system by creating special picture cards. According to the physiotherapist’s assessment, they would put a picture on the head of the patient’s bed if the patient needed to be periodically turned in bed or if the patient needed to be activated in some other way. We even ended up having cards that inform about a patient’s hearing loss and other impairments that need to be considered by caregivers. What was nice was that they first took the time to train all the caregivers on how to respond to these cards. They took the time to measure, and what they found in their project was that indeed the patients who were testing the picture card method had fewer strokes and they were cared for a little bit more actively. It was then easier to also raise interest in this method in other departments. We are now at the stage where we are putting a lot of emphasis on communication to spread the change.

R-HM: On the one hand, this is an important issue directly related to patient well-being, yet the solution is relatively simple, making it easier to measure the impact. As soon as you have more variables, such as when we address the journey more comprehensively, measuring the impact also becomes more complex. In the field of design, there is an established understanding that impact should be measured. Every new design project begins with mapping the context and formulating the problem to be solved. We need to approach the process openly and should not define the problem too early. When should we decide what we are measuring?

PT: Our principle is that this should be determined before you start doing it. If we already know that we want to try something, then why not ask the question right away: What should it improve? However, it may also be the case that if the first outcome indicator does not show improvement, it does not mean that there is no improvement at all. In that case, it should be tried again. For example, if patients’ bedsores do not heal, their experience may improve because they receive more attention and care. In this project, the patient’s experience was not directly measured, but it is indeed important to constantly consider the patient’s feedback in ongoing projects.

The success of the physiotherapy project could indeed be attributed to the fact that the change was small. Since it did not significantly increase anyone’s workload, it was possible to move forward quickly without much effort to create the prerequisites for the change. One concept that I like to apply is Highly Adoptable Quality Improvement, according to which the success of a change depends on two interconnected factors – how much it affects the workload and how interested people are in the change. If the change does not affect the workload much or even reduces it, then the interest does not need to be particularly high. But if the change requires an increase in workload, even in the short term, then interest in the project must be much greater. Unfortunately, most large projects that we want to implement, even if they reduce the workload in the long term, will certainly increase it in the short term. Therefore, we need to emphasise the importance of generating increased interest in going along with the change.

R-HM: One part of mapping all involved parties is not just creating a list of everyone but only those who have an impact on the project or an interest in it, those who are affected by it, and how they are affected by it. Also, how people and positions are interrelated. In the context of this tool, we ask how to further arouse the interest of those who have greater influence to lead or support the change.

We have constantly seen in our projects that marginalised groups are also very important, such as caregivers or even patients’ relatives, who bear the responsibility and burden of caring for the patient or loved one. Speaking of the patient’s relatives, they are often unable to participate in decision-making and discussing post-hospital care. Therefore, this valuable information often does not reach them when going back home. How can we provide information effectively, and it doesn’t necessarily have to involve making a brochure or a website.

PT: The involvement of a patient’s relatives is a whole separate realm. When trying to implement US quality standards in Estonia, involving relatives was one aspect where we found gaps in our mapping results at NEMC. But not because we don’t want to, but because we are actually very individualistic when it comes to illness. Not everyone has a close relative who is willing to support them throughout their treatment journey, which creates a complex situation where the vulnerable patient has to acquire all the information themselves and manage with it afterwards. But we do our best, and for example cancer patients receive information from at least three different sources before they go home. This is because the whole situation is emotionally very challenging for them, and we don’t expect everything to be understood at once. Therefore, we are increasingly moving towards offering remote support so that patients can also get in touch whenever necessary from home.

DK: One of the key insights of the patient-centred care project was that people want and expect to be treated holistically, not just identified by their diagnosis or illness. For example, maybe a patient is supposed to receive chemotherapy and his or her pet is left unattended or a young female patient is the sole caregiver for her mother and feels that chemotherapy is affecting her health to the extent that she can no longer care for her mother – in such cases, the patient may refuse chemotherapy. Our conversations have revealed that various fears, prejudices, attitudes and emotions, which may not always be immediately visible or discovered, can be significant barriers to treatment and thus the effectiveness of the treatment. I can’t help but ask how much do we really use the holistic approach in healthcare?

PT: The keyword here is “we try,” because unfortunately we have to face obvious limitations in healthcare. For every 1,000 patients, we have three times fewer nurses compared to Finland. The number of doctors is also one of the lowest in OECD countries. The duration of a visit is limited to 20 or 15 minutes. This opportunity to ask the patient not only what is wrong with them, but also what is important to them, is limited precisely because there is very little time for it. I can honestly say that there is no doctor who does not care about people, but the question is whether the environment in which they work and the time allotted to them allow them to express that care. Inevitably, there is always a queue in the waiting room. Already today, many doctors cannot take a lunch break during the clinic’s working hours because otherwise the queue would become too long.

In healthcare, there’s a movement called “What Matters To You.” Instead of asking the patient “What’s the matter?”, the question is about what is important to the patient in their life. This question also assumes the capability to actually change or do things differently – but today’s options for implementing all this are rather poor. Ultimately, it’s in our best interest to understand what holds people back. For example, if a patient has cancer at a treatable stage but refuses treatment, and if there are no opportunities for the patient to receive counselling, then we find ourselves in a situation where that chemotherapy might not happen.

In my view, the future of healthcare definitely needs specialists who do not necessarily need to possess in-depth medical knowledge, but rather have a background in coaching and basic understanding of the diseases they advise patients on. They should have the time to understand patients’ personal needs and devise a plan to better address them throughout the course of the treatment.

R-HM: The topics Daniel brought up fall within the scope of local government services in our system. Unfortunately, there is simply a lack of connection between different public services. To cover even a small part of this issue, hospitals have taken the initiative to create positions for social workers. However, the need for a holistic approach is only one aspect of this. It has seemed to me that another reason why people tend to talk about the patient on the basis of their diagnosis rather than their name or the bed they are in is compassion exhaustion. Such burdensome situations simply become overwhelming.

PT: On the other hand, a different kind of exhaustion can arise when you keep seeing day to day the patients you cannot help. At times, knowing that you have been able to do something can actually work as an energy boost. Especially when considering what lies ahead in terms of an ageing patient population. They may have many health issues none of which may be curable, but perhaps you can support them to live independently at home. We are trained to cure diseases that are curable. Personally, you want to do something but you see that your current tools are no longer sufficient. Even in the social services there are currently not enough resources to deal with such patients. However, maybe by thinking a little differently about that patient you can still support their well-being.

DK: The designer’s task is to be a connector of different stakeholders and to bring out the context and mindset of the patient, approaching with a fresh perspective and helping identify the problem areas. When looking at the problem from only one party’s perspective without considering others, we may become one-sided and the solutions may not fit the holistic context.

PT: The designer can definitely be of help, and I would encourage the designer to think of themselves as educators. At some point, the designer leaves the hospital, and perhaps we won’t succeed in ending up with collaborative projects, but the skillset itself is necessary. The ability to conduct observations and interviews and ask the right questions. The next time we do a collaborative project and need to conduct interviews with patients, for example, we could do them together. This could be led by the designer, alongside a nurse or whoever is interested, to implement this in the future.

DK: In conclusion, what assumptions and expectations should be brought into a collaboration to ensure its positive impact? Essentially, we are talking about two impacts – providing students with the skills and experiences necessary for their future work and addressing important challenges from the hospital’s perspective.

R-HM: What has happened so far and why it is so valuable to us is literally real-life exposure to the actual environment, and over the years we have built mutual trust, which is certainly very valuable. When we asked the hospital to provide topics for students to solve, there hasn’t been any concern for years – there have been plenty of topics as well as cooperative personnel. We expect that the collaboration partners in hospitals take enough time for students and that they will be available for interviews, observations, and everything else. Design education inherently involves practice, so learning by doing is important in terms of our learning outcomes.

An amazing example was during the design sprint that took place last autumn, where as part of an international project a group of students got to witness open-heart surgery during their first design project. One Latvian student wrote in the feedback about it being ‘life-changing’. Not all schools have such a good collaboration platform, so from our perspective it is definitely a wonderful opportunity.

PT: I believe we can enhance the teaching impact – not only does the student learn, so does the healthcare worker. Most of this process is certainly necessary, and the question is how the impact manifests along the patient journey. The more integral the role of the healthcare or hospital employee who continues to work on the project, the greater the likelihood that the solution will be embraced more widely and efforts will continue towards its implementation. Unfortunately, we cannot ignore the fact that even if an idea is widely accepted and held to be important, it often does not materialise, as it is too resource-intensive within limited conditions.

But here are two things that might help. One thing would be reducing friction. Changes are often resource-intensive because they face obstacles. As mentioned earlier, the ecosystem is vast and the circle of involvement is wide, but perhaps we can better prepare teams to engage those individuals who are crucial to the future success of the project and can help implement the change.

Another thing I was taught when I started with quality management in healthcare is to think about what you can do to reduce the frustration in healthcare workers. Instead of initially focusing on improving the patient journey, it would be wise to think about how to make the healthcare worker’s life better, so they have the space to think about the patient in the first place. That’s why we’ve also focused on improving the working environment at the North Estonia Medical Centre. I think this could be a focus for us the next time we engage in a collaboration project with the Estonian Academy of Arts.